Ten years ago this week, two international collaborations of groups of scientists, including a large contingent from Caltech, confirmed that they had found conclusive evidence for the Higgs boson, an elusive elementary particle, first predicted in a series of articles published in the mid-1960s, that is thought to endow elementary particles with mass.

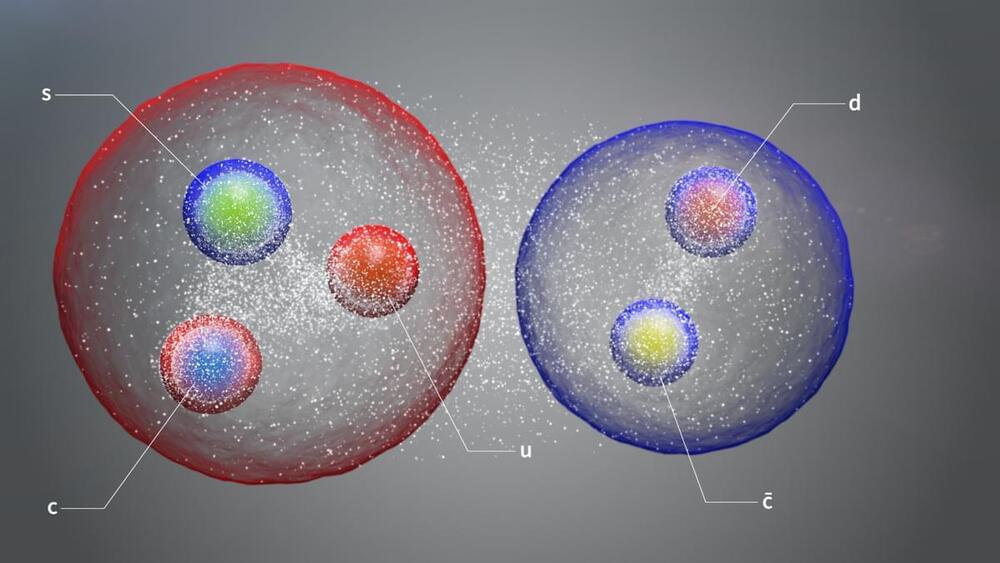

Fifty years prior, as theoretical physicists endeavored to understand the so-called electroweak theory, which describes both electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force (involved in radioactive decay), it became apparent to Peter Higgs, working in the UK, and independently to François Englert and Robert Brout, in Belgium, as well as U.S. physicist Gerald Guralnik and others, that a previously unidentified field that filled the universe was required to explain the behavior of the elementary particles that compose matter. This field, the Higgs field, would lead to a particle with zero spin, significant mass, and have the ability to spontaneously break the symmetry of the earliest universe, allowing the universe to materialize. That particle became known as the Higgs boson.

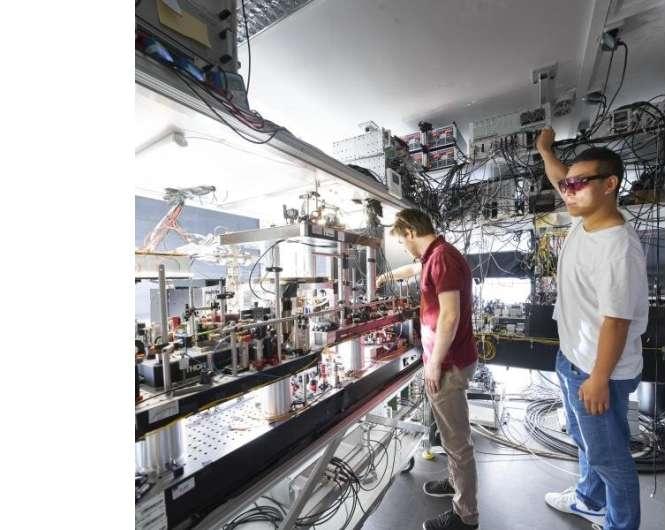

Over the decades that followed, experimental physicists first devised and then developed the instruments and methods required to detect the Higgs boson. The most ambitious of these projects was the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which is operated by the European Organization for Nuclear Research, or CERN. Since the planning of the LHC in the late 1980s, the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation have worked in collaboration with CERN to provide funding and technology know-how, and to support thousands of scientists helping to search for the Higgs.