A Bose-Einstein condensate of europium atoms provides a new experimental platform for studying quantum spin interactions.

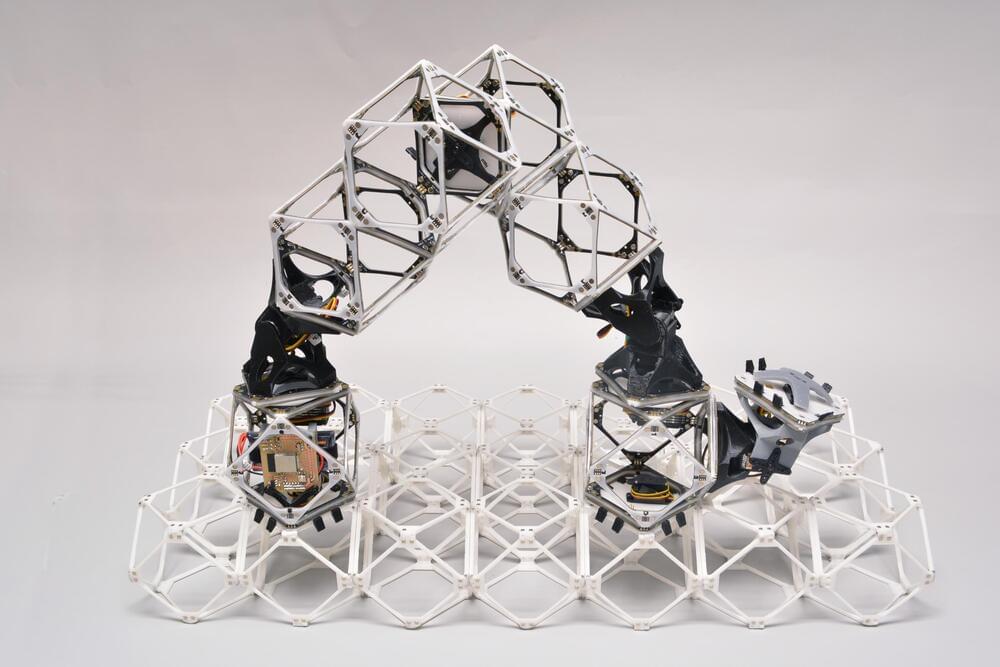

The new work, from MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms (CBA), builds on years of research, including recent studies demonstrating that objects such as a deformable airplane wing and a functional racing car could be assembled from tiny identical lightweight pieces — and that robotic devices could be built to carry out some of this assembly work. Now, the team has shown that both the assembler bots and the components of the structure being built can all be made of the same subunits, and the robots can move independently in large numbers to accomplish large-scale assemblies quickly.

The new work is reported in the journal Nature Communications Engineering, in a paper by CBA doctoral student Amira Abdel-Rahman, Professor and CBA Director Neil Gershenfeld, and three others.

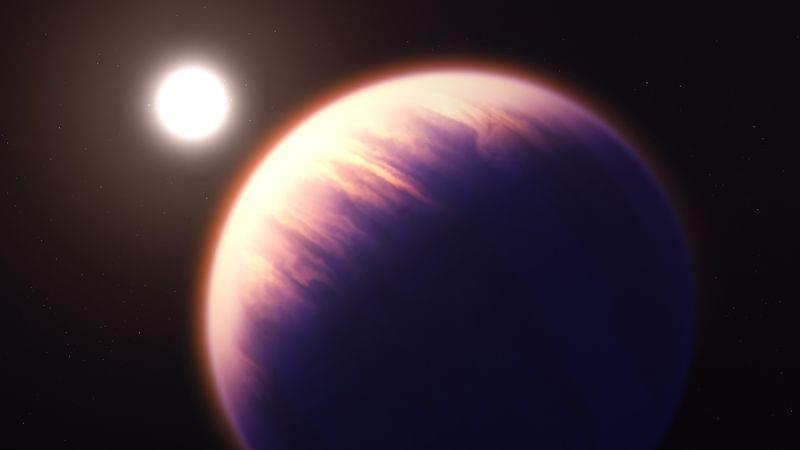

The James Webb Space Telescope has captured a detailed molecular and chemical portrait of a faraway planet’s skies, scoring another first for the exoplanet science community.

WASP-39b, otherwise known as Bocaprins, can be found orbiting a star some 700 light-years away. It is an exoplanet — a planet outside our solar system — as massive as Saturn but much closer to its host star, making for an estimated temperature of 1,600 degrees Fahrenheit (871 degrees Celsius) emitting from its gases, according to NASA. This “hot Saturn” was one of the first exoplanets that the Webb telescope examined when it first began its regular science operations.

The new readings provide a full breakdown of Bocaprins’ atmosphere, including atoms, molecules, cloud formations (which appear to be broken up, rather than a single, uniform blanket as scientists previously expected) and even signs of photochemistry caused by its host star.

By using a chain of atoms to simulate a black hole’s event horizon, researchers have shown that Hawking radiation may exist just as the late physicist described. Scientists have created a lab-grown black hole analog to test one of Stephen Hawking’s most famous theories — and it behaves just how he predicted.

Sound waves, like an invisible pair of tweezers, can be used to levitate small objects in the air. Although DIY acoustic levitation kits are readily available online, the technology has important applications in both research and industry, including the manipulation of delicate materials like biological cells.

Researchers at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and the University of New South Wales (UNSW) have recently demonstrated that in order to precisely control a particle using ultrasonic waves, it is necessary to take into account both the shape of the particle and how this affects the acoustic field. Their findings were recently published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Sound levitation happens when sound waves interact and form a standing wave with nodes that can ‘trap’ a particle. Gorkov’s core theory of acoustophoresis, the current mathematical foundation for acoustic levitation, makes the assumption that the particle being trapped is a sphere.

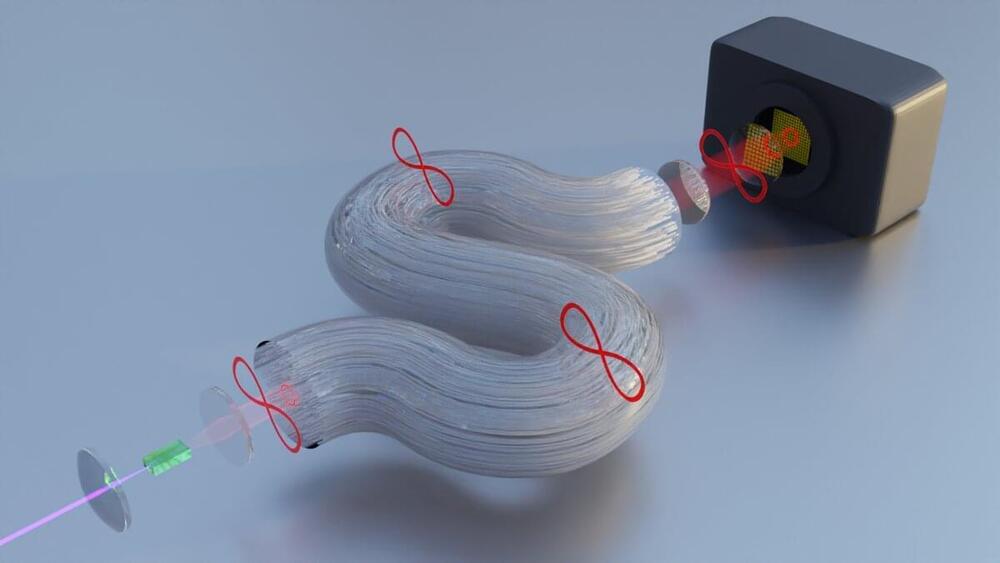

Invented in 1970 by Corning Incorporated, low-loss optical fiber became the best means to efficiently transport information from one place to another over long distances without loss of information. The most common way of data transmission nowadays is through conventional optical fibers—one single core channel transmits the information. However, with the exponential increase of data generation, these systems are reaching information-carrying capacity limits.

Thus, research now focuses on finding new ways to utilize the full potential of fibers by examining their inner structure and applying new approaches to signal generation and transmission. Moreover, applications in quantum technology are enabled by extending this research from classical to quantum light.

In the late 50s, the physicist Philip W. Anderson (who also made important contributions to particle physics and superconductivity) predicted what is now called Anderson localization. For this discovery, he received the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physics. Anderson showed theoretically under which conditions an electron in a disordered system can either move freely through the system as a whole, or be tied to a specific position as a “localized electron.” This disordered system can for example be a semiconductor with impurities.

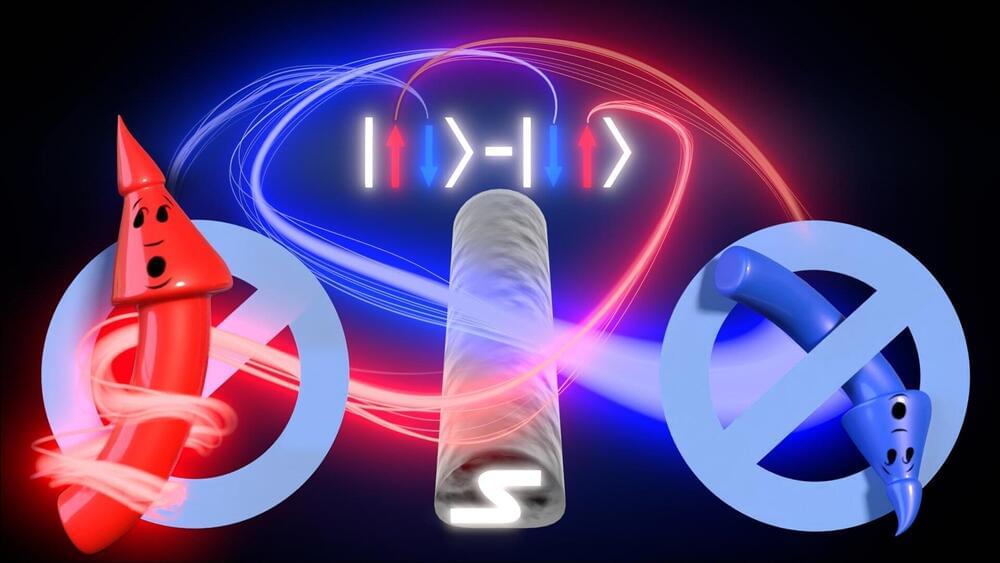

Physicists at the University of Basel have experimentally demonstrated for the first time that there is a negative correlation between the two spins of an entangled pair of electrons from a superconductor. For their study, the researchers used spin filters made of nanomagnets and quantum dots, as they report in the scientific journal Nature.

The entanglement between two particles is among those phenomena in quantum physics that are hard to reconcile with everyday experiences. If entangled, certain properties of the two particles are closely linked, even when far apart. Albert Einstein described entanglement as a “spooky action at a distance.” Research on entanglement between light particles (photons) was awarded this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics.

Two electrons can be entangled as well—for example in their spins. In a superconductor, the electrons form so-called Cooper pairs responsible for the lossless electrical currents and in which the individual spins are entangled.

Physicists have long struggled to explain why the universe started out with conditions suitable for life to evolve. Why do the physical laws and constants take the very specific values that allow stars, planets and ultimately life to develop? The expansive force of the universe, dark energy, for example, is much weaker than theory suggests it should be—allowing matter to clump together rather than being ripped apart.

A common answer is that we live in an infinite multiverse of universes, so we shouldn’t be surprised that at least one universe has turned out as ours. But another is that our universe is a computer simulation, with someone (perhaps an advanced alien species) fine-tuning the conditions.

The latter option is supported by a branch of science called information physics, which suggests that space-time and matter are not fundamental phenomena. Instead, the physical reality is fundamentally made up of bits of information, from which our experience of space-time emerges. By comparison, temperature “emerges” from the collective movement of atoms. No single atom fundamentally has temperature.

Superconducting materials are characterized by the fact that they lose their electrical resistance below a certain temperature, the so-called transition temperature. In principle, they would be ideal for transporting electrical energy over very long distances from the electricity producer to the consumer.

Numerous energy challenges would be solved in one fell swoop: For example, the electricity generated by wind turbines on the coast could be channeled inland without losses. However, this would only be possible if materials were available that have superconducting properties at normal room and ambient temperatures.

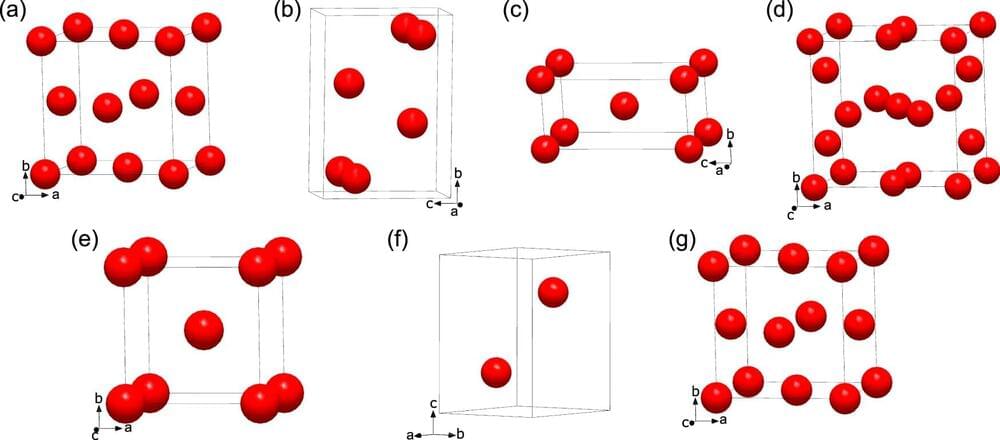

In 2019, an unusually high transition temperature of minus 23 degrees Celsius was measured in experiments coordinated by the Max Planck Institute in Mainz. The measurement took place at a compression pressure of 170 gigapascals—1.7 million times higher than the pressure of the Earth’s atmosphere. The material was a lanthanum hydride (LaH10+δ), a compound of atoms of the metal lanthanum with hydrogen atoms. The report on these experiments and other similar reports remain highly controversial. They have internationally aroused great interest in research on lanthanum hydrides with different compositions and structures.

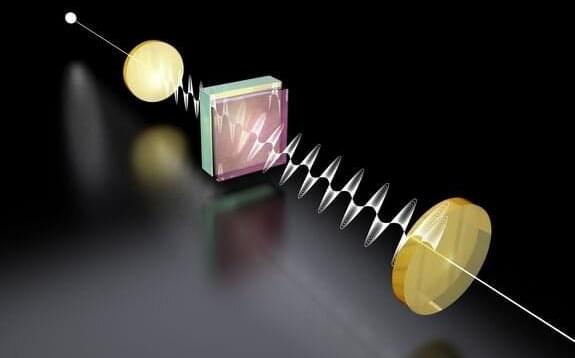

The fine structure constant is one of the most important natural constants of all. At TU Wien, a remarkable way of measuring it has been found—it shows up as a rotation angle.

One over 137: This is one of the most important numbers in physics. It is the approximate value of the so-called fine structure constant—a physical quantity that is of outstanding importance in atomic and particle physics.

There are many ways to measure the fine structure constant—usually it is measured indirectly, by measuring other physical quantities and using them to calculate the fine structure constant. At TU Wien, however, an experiment has now been performed, in which the fine structure constant itself can be directly measured—as an angle.