Andrew Strominger is a theoretical physicist at Harvard. Please support this podcast by checking out our sponsors:

- Eight Sleep: https://www.eightsleep.com/lex to get special savings.

- Rocket Money: https://rocketmoney.com/lex.

- Indeed: https://indeed.com/lex to get $75 credit.

- ExpressVPN: https://expressvpn.com/lexpod to get 3 months free.

EPISODE LINKS:

Andrew’s website: https://www.physics.harvard.edu/people/facpages/strominger.

Andrew’s papers:

Soft Hair on Black Holes: https://arxiv.org/abs/1601.00921

Photon Rings Around Warped Black Holes: https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.

PODCAST INFO:

Podcast website: https://lexfridman.com/podcast.

Apple Podcasts: https://apple.co/2lwqZIr.

Spotify: https://spoti.fi/2nEwCF8

RSS: https://lexfridman.com/feed/podcast/

Full episodes playlist: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrAXtmErZgOdP_8GztsuKi9nrraNbKKp4

Clips playlist: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrAXtmErZgOeciFP3CBCIEElOJeitOr41

OUTLINE:

0:00 — Introduction.

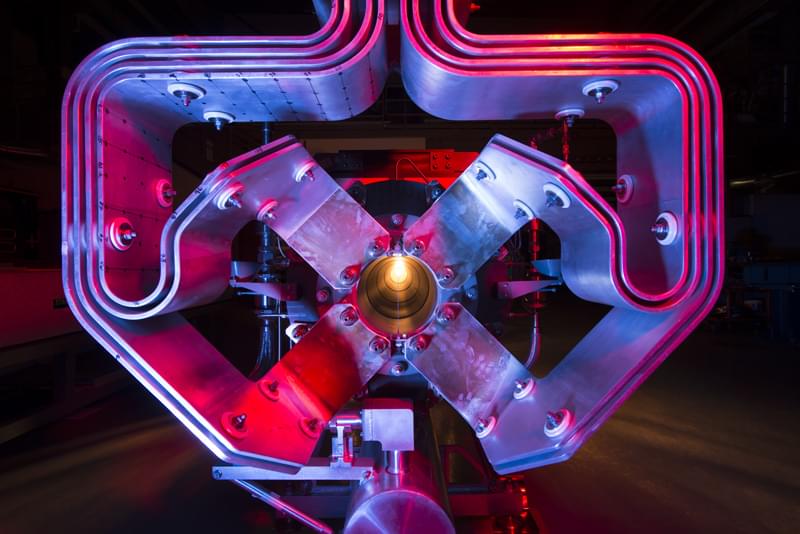

1:12 — Black holes.

6:16 — Albert Einstein.

25:44 — Quantum gravity.

29:56 — String theory.

40:44 — Holographic principle.

48:41 — De Sitter space.

53:53 — Speed of light.

1:00:40 — Black hole information paradox.

1:08:20 — Soft particles.

1:17:27 — Physics vs mathematics.

1:26:37 — Theory of everything.

1:41:58 — Time.

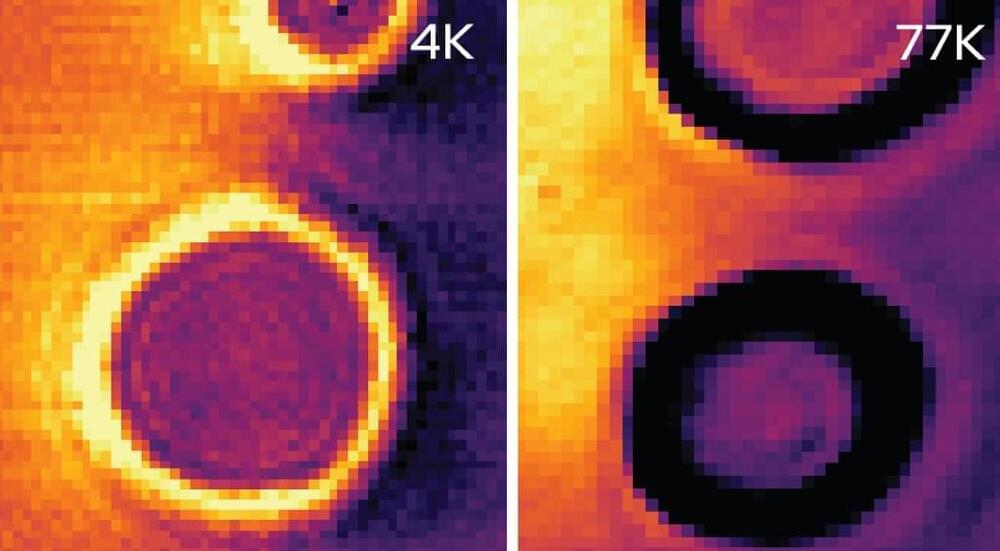

1:44:24 — Photon rings.

2:00:05 — Thought experiments.

2:08:26 — Aliens.

2:14:04 — Nuclear weapons.

SOCIAL:

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/lexfridman.

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/lexfridman.

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/lexfridman.

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/lexfridman.

- Medium: https://medium.com/@lexfridman.

- Reddit: https://reddit.com/r/lexfridman.

- Support on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/lexfridman