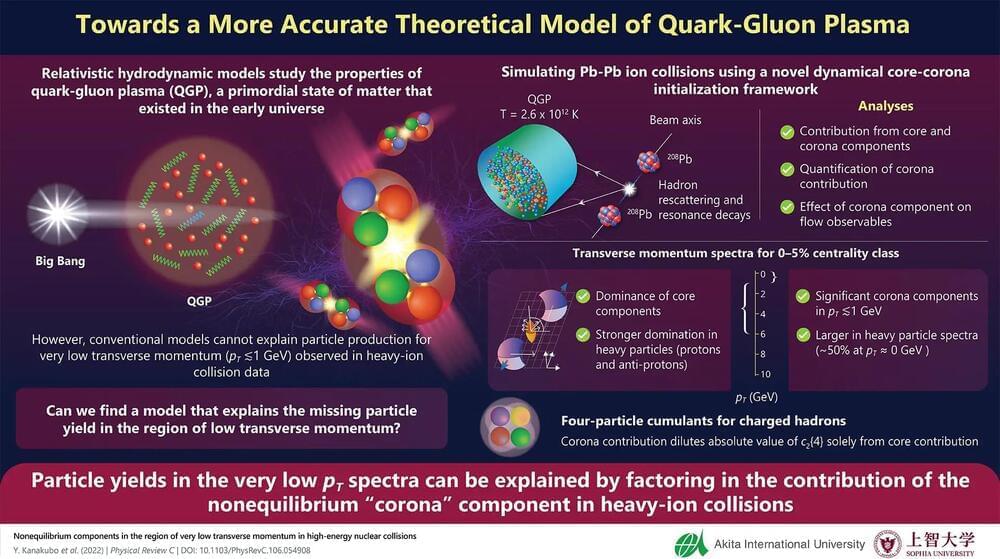

The properties of quark-gluon plasma (QGP), the primordial form of matter in the early universe, is conventionally described using relativistic hydrodynamical models. However, these models predict low particle yields in the low transverse momentum region, which is at odds with experimental data. To address this discrepancy, researchers from Japan now propose a novel framework based on a “core-corona” picture of QGP, which predicts that the corona component may contribute to the observed high particle yields.

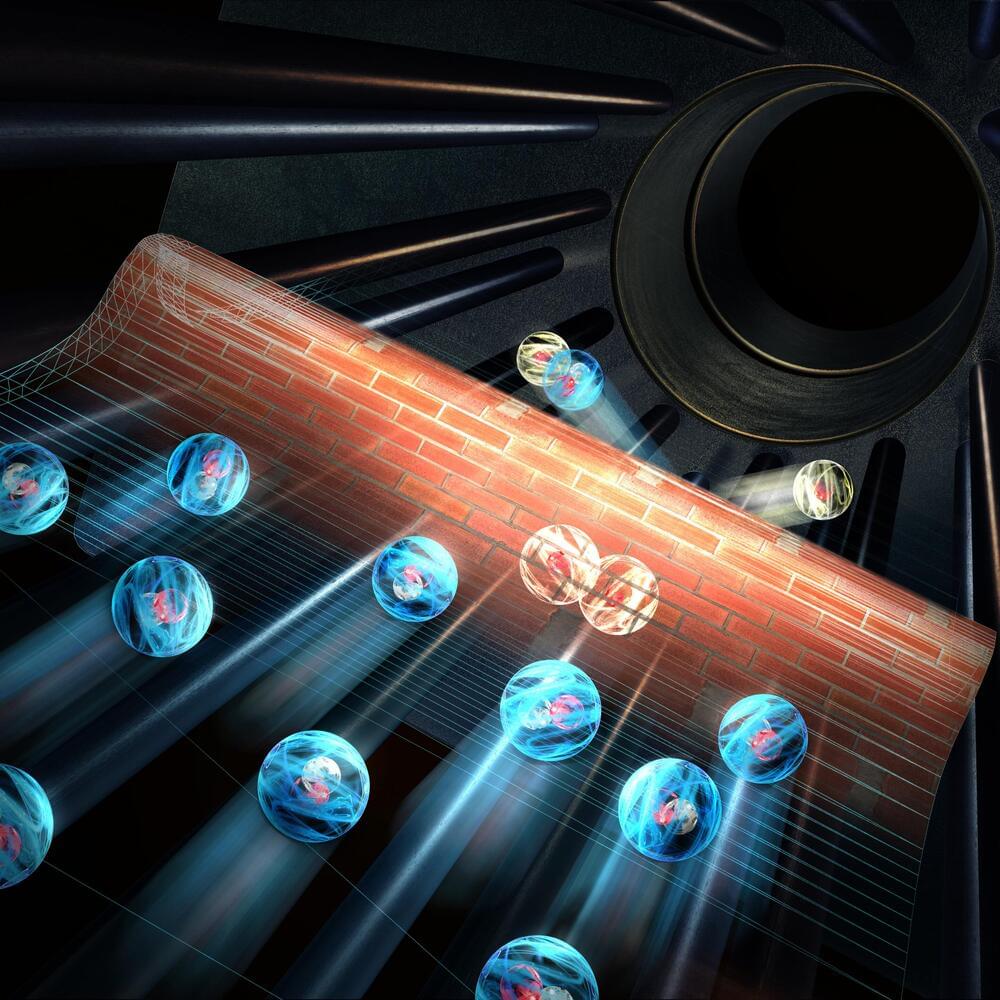

Research in fundamental science has revealed the existence of quark-gluon plasma (QGP) – a newly identified state of matter – as the constituent of the early universe. Known to have existed a microsecond after the Big Bang, the QGP, essentially a soup of quarks and gluons, cooled down with time to form hadrons like protons and neutrons – the building blocks of all matter. One way to reproduce the extreme conditions prevailing when QGP existed is through relativistic heavy-ion collisions. In this regard, particle accelerator facilities like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) have furthered our understanding of QGP with experimental data pertaining to such collisions.

Meanwhile, theoretical physicists have employed multistage relativistic hydrodynamic models to explain the data, since the QGP behaves very much like a perfect fluid. However, there has been a serious lingering disagreement between these models and data in the region of low transverse momentum, where both the conventional and hybrid models have failed to explain the particle yields observed in the experiments.