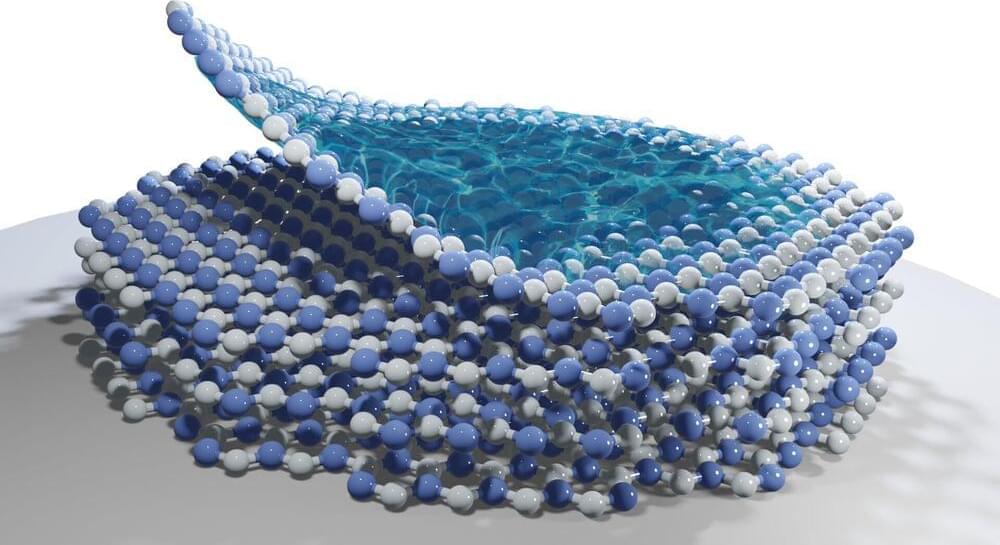

Polarons are localized quasiparticles that result from the interaction between fermionic particles and bosonic fields. Specifically, polarons are formed when individual electrons in crystals distort their surrounding atomic lattice, producing composite objects that behave more like a massive particles than electron waves.

Feliciano Giustino and Weng Hong Sio, two researchers at the University of Texas at Austin, recently carried out a study investigating the processes underpinning the formation of polarons in 2D materials. Their paper, published in Nature Physics, outlines some fundamental mechanisms associated with these particles’ formation that had not been identified in previous works.

“Back in 2019, we developed a new theoretical and computational framework to study polarons,” Feliciano Giustino, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told Phys.org. “One thing that caught our attention is that many experimental papers discuss polarons in 3D bulk materials, but we could find only a couple of papers reporting observations of these particles in 2D. So, we were wondering whether this is just a coincidence, or else polarons in 2D are more rare or more elusive than in 3D, and our recent paper addresses this question.”