Scientists want to use quantum mechanics to capture higher-resolution images of the night sky.

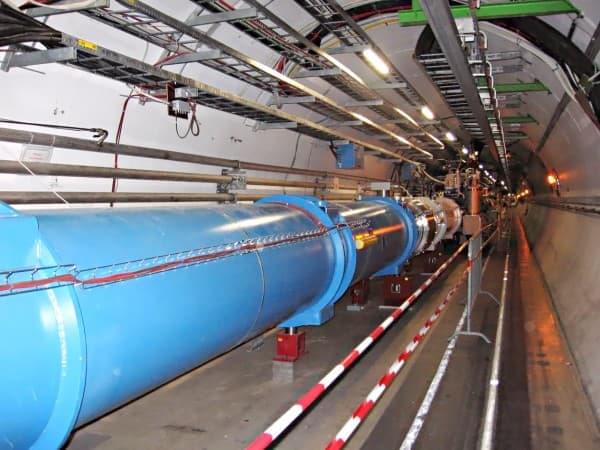

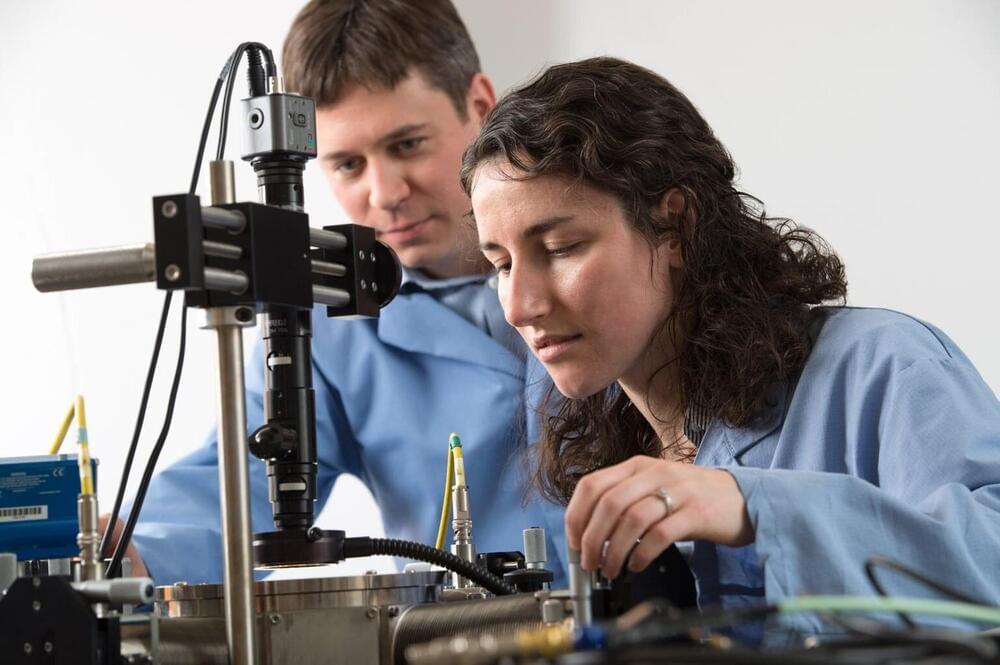

For the purposes of astronomy, the two beams are collected by two telescopes that are separated by some distance (called baseline interferometry). But despite its effectiveness, classic interferometry is subject to some limitations. Andrei Nomerotski, an astrophysicist with the BNL and a co-author on the paper, explained to Universe Today via email.

“Interferometry is a way to increase the effective aperture of telescopes and to improve the angular resolution or astrometric precision,” he said. “The main difficulty here is to maintain the stability of this optical path to very high precision, which should be much smaller than the photon wavelength, to preserve the photon’s phase. This limits the practical baselines to a few hundred meters.”

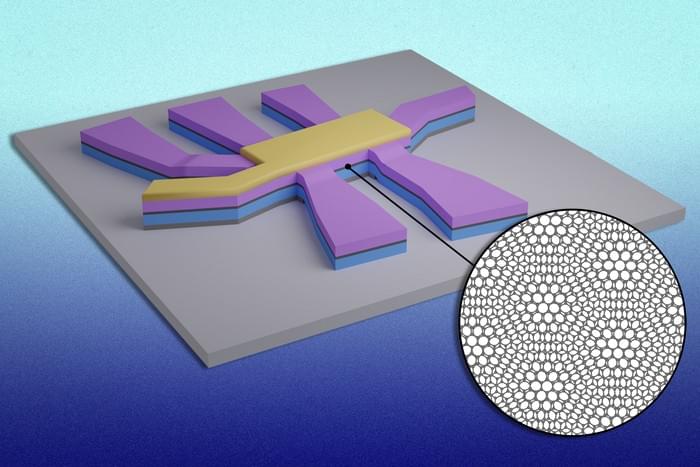

In recent years, scientists have investigated the possibility of using quantum principles to enable next-generation astronomy. The basic idea is that photons could be transferred between observatories without physical connections that are expensive to build and maintain. The key is to take advantage of quantum entanglement, a phenomenon where particles interact and share the same quantum state — despite being separated by considered distance.