Quantum technologies—and quantum computers in particular—have the potential to shape the development of technology in the future. Scientists believe that quantum computers will help them solve problems that even the fastest supercomputers are unable to handle yet. Large international IT companies and countries like the United States and China have been making significant investments in the development of this technology. But because quantum computers are based on different laws of physics than conventional computers, laptops, and smartphones, they are more susceptible to malfunction.

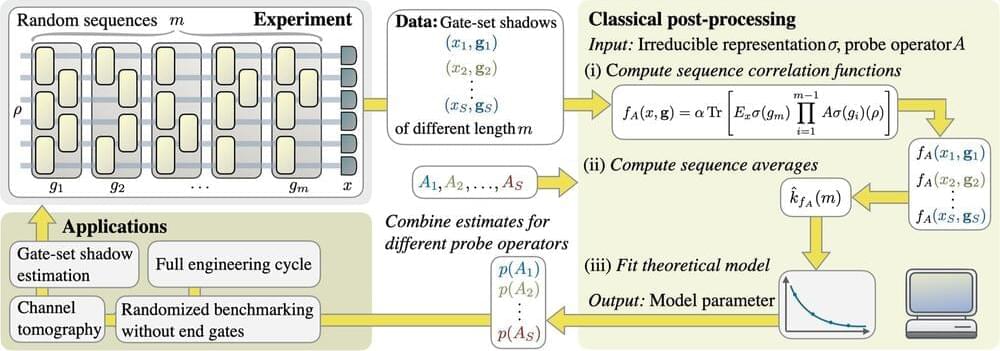

An interdisciplinary research team led by Professor Jens Eisert, a physicist at Freie Universität Berlin, has now found ways of testing the quality of quantum computers. Their study on the subject was recently published in the scientific journal Nature Communications. These scientific quality control tests incorporate methods from physics, computer science, and mathematics.

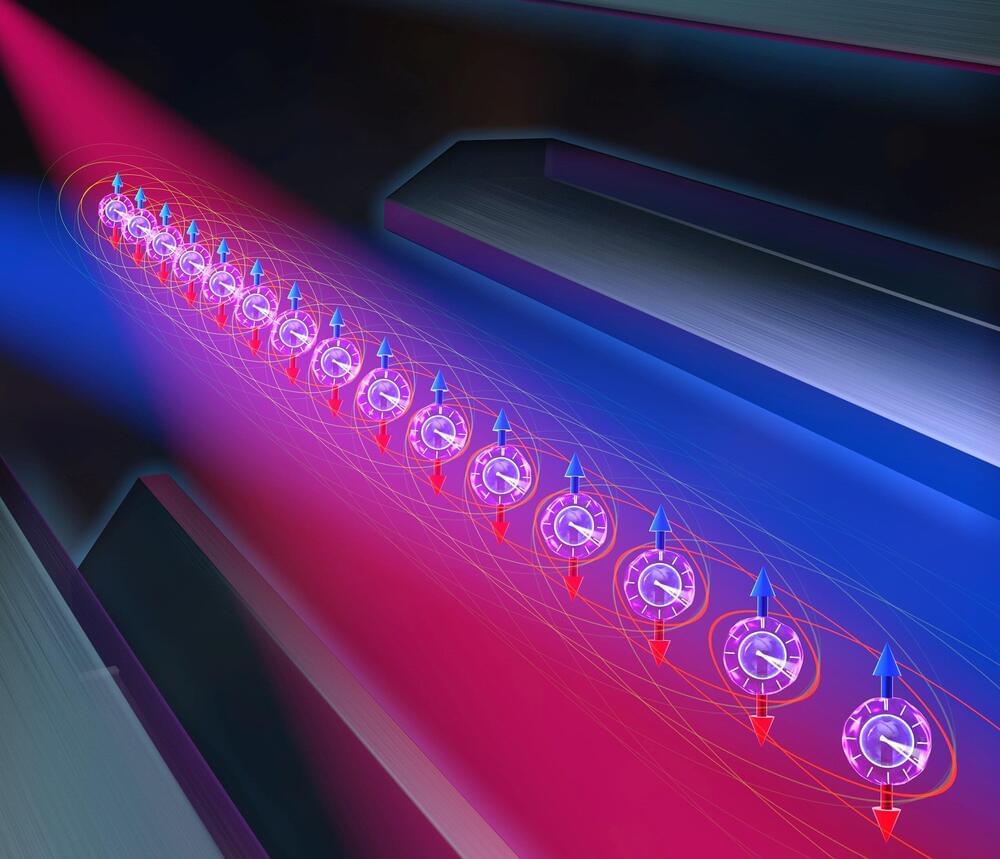

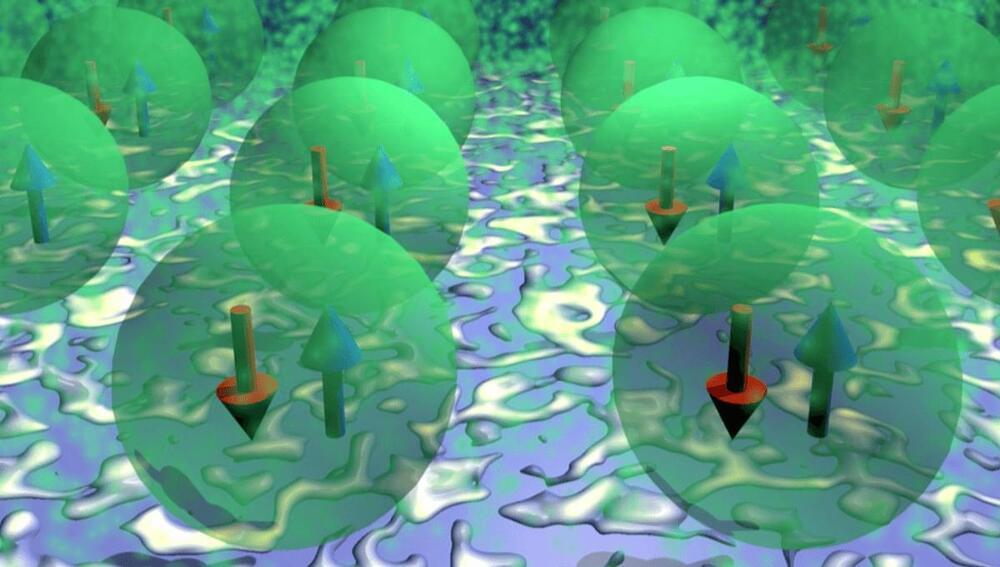

Quantum physicist at Freie Universität Berlin and author of the study, Professor Jens Eisert, explains the science behind the research. “Quantum computers work on the basis of quantum mechanical laws of physics, in which individual atoms or ions are used as computational units—or to put it another way—controlled, minuscule physical systems. What is extraordinary about these computers of the future is that at this level, nature functions extremely and radically differently from our everyday experience of the world and how we know and perceive it.”