From the article:

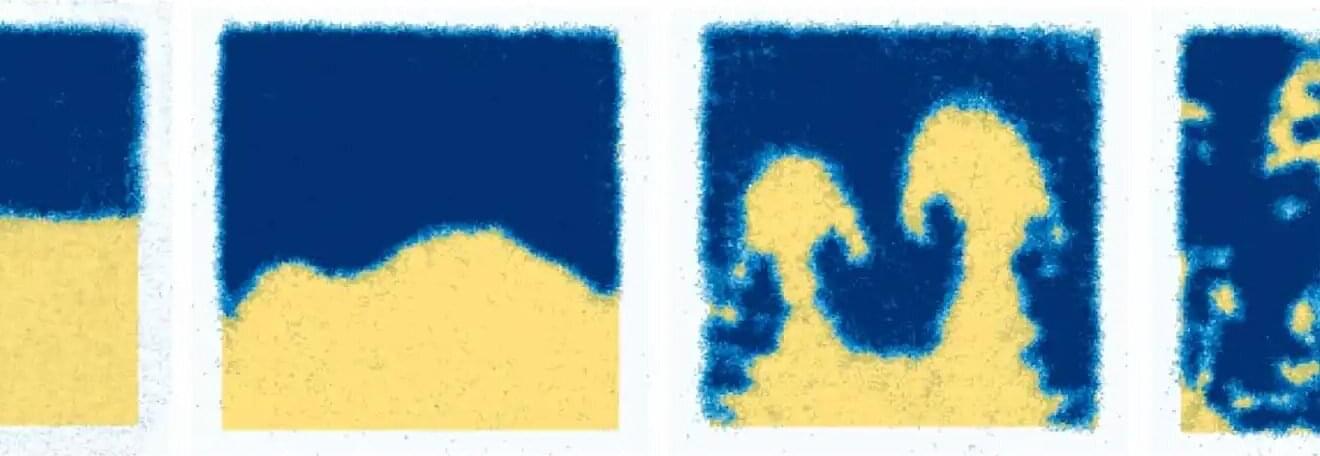

Quantum mechanics requires a distinction between an observer — such as the scientist carrying out an experiment — and the system they observe. The system tends to be something small and quantum, like an atom. The observer is big and far away, and thus well described by classical physics. Shaghoulian observed that this split was analogous to the kind that enlarges the Hilbert spaces of topological field theories. Perhaps an observer could do the same to these closed, impossibly simple-seeming universes?

In 2024, Zhao moved to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she began to work on the problem of how to put an observer into a closed universe. She and two colleagues —Daniel Harlow and Mykhaylo Usatyuk — thought of the observer as introducing a new kind of boundary: not the edge of the universe, but the boundary of the observer themself. When you consider a classical observer inside a closed universe, all the complexity of the world returns, Zhao and her collaborators showed.

The MIT team’s paper(opens a new tab) came out at the beginning of 2025, around the same time that another group came forward with a similar idea(opens a new tab). Others chimed in(opens a new tab) to point out connections to earlier work.

At this stage, everyone involved emphasizes that they don’t know the full solution. The paradox itself may be a misunderstanding, one that evaporates with a new argument. But so far, adding an observer to the closed universe and trying to account for their presence may be the safest path.

“Am I really confident to say that it’s right, it’s the thing that solves the problem? I cannot say that. We try our best,” Zhao said.

If the idea holds up, using the subjective nature of the observer as a way to account for the complexity of the universe would represent a paradigm shift in physics. Physicists typically seek a view from nowhere, a stand-alone description of nature. They want to know how the world works, and how observers like us emerge as parts of the world. But as physicists come to understand closed universes in terms of private boundaries around private observers, this view from nowhere seems less and less viable. Perhaps views from somewhere are all that we can ever have.