To learn QM or quantum computing in depth, check out: https://brilliant.org/arvinash — Their course called “Quantum computing” is one of the best. You can sign up for free! And the first 200 people will get 20% off their annual membership. Enjoy!

Chapters:

0:00 — Weirdness of quantum mechanics.

1:51 — Intuitive understanding of entanglement.

4:46 — How do we know that superposition is real?

5:40 — The EPR Paradox.

6:50 — Spooky action and hidden variables.

7:51 — Bell’s Inequality.

9:07 — How are objects entangled?

10:03 — Is spooky action at a distance true?

10:40 — What is quantum entanglement really?

11:31 — How do two particles become one?

13:03 — What is non locality?

14:05 — Can we use entanglement for communication?

15:08 — Advantages of quantum entanglement.

15:49 — How to learn quantum computing.

Summary:

Albert Einstein described Entanglement as “spooky action at a distance,” where doing something to one of a But it’s not spooky action at a distance, at all. So what is entanglement?

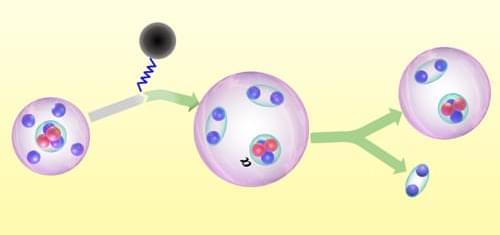

Electrons have a quantum property called spin that makes them act like little magnets. We’ll always measure it pointing in one direction or the opposite: up or down, say. If we entangle two electrons so that their spins are always pointing in opposite directions, the two spins are said to be correlated. If we entangle the two electrons in this way – and fire them in opposite directions, we don’t know which one of the pair is up and which one is down until we make a measurement. If we find that electron 1 is spin up. We know the spin of electron 2 must be down.

Why isn’t this like a pair of gloves? The handedness of the gloves is there from the start. It never changes. With entangled particles that’s not the case. They are in a superposition. Prior to measurement, there is no definite answer.

How do we know superposition is real? The double slit experiment is good evidence. Entangled particles are stranger, because a measurement on one particle determines the outcome for both of them.