How Does The Neutral Atom Approach Compare

The neutral atom approach is a well-known and extensively investigated approach to quantum computing. The approach offers numerous advantages, especially in terms of scalability, expense, error mitigation, error correction, coherence, and simplicity.

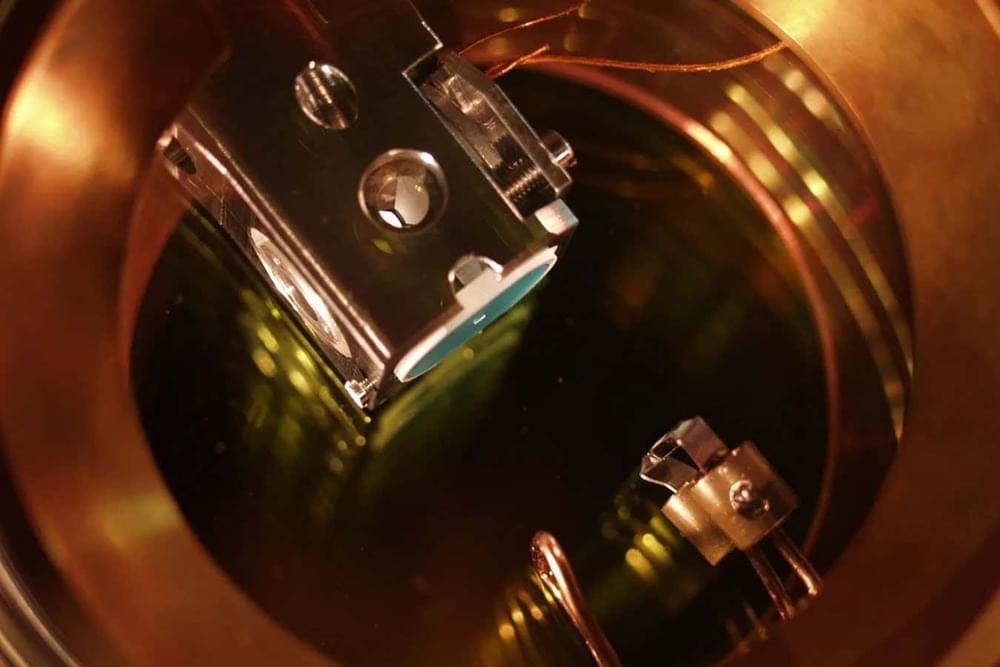

Neutral atom quantum computing utilizes individual atoms, typically alkali atoms like rubidium or cesium, suspended and isolated in a vacuum and manipulated using precisely targeted laser beams. These atoms are not ionized, meaning they retain all their electrons and do not carry an electric charge, which distinguishes them from trapped ion approaches. The quantum states of these neutral atoms, such as their energy levels or the orientation of their spins, serve as the basis for qubits. By employing optical tweezers—focused laser beams that trap and hold the atoms in place—arrays of atoms can be arranged in customizable patterns, allowing for the encoding and manipulation of quantum information.