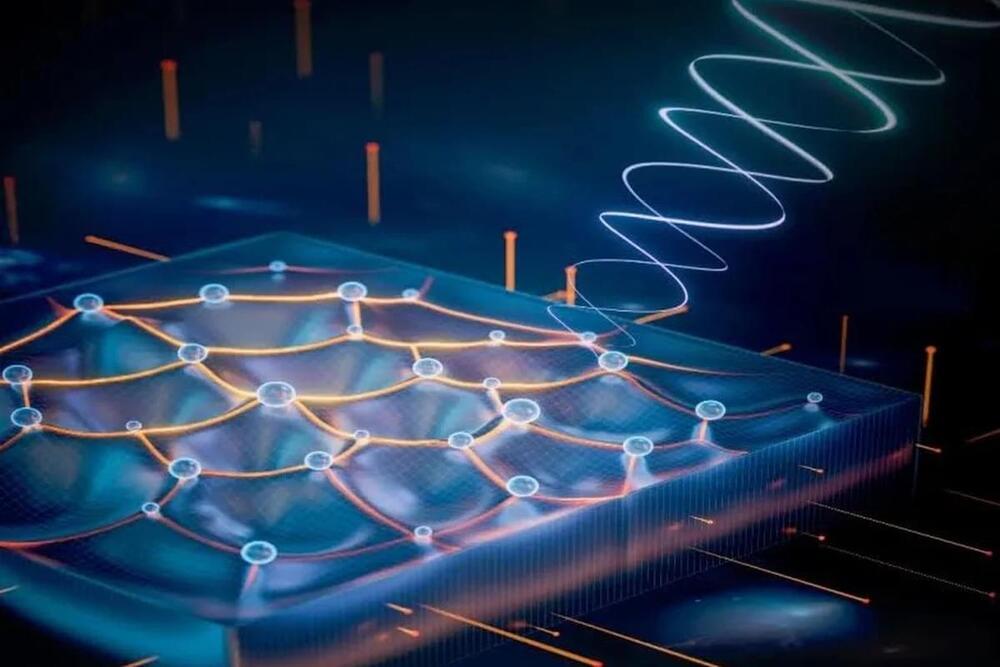

BREAD’s innovative approach to dark matter detection uses a coaxial “dish” antenna to scan for mysterious particles.

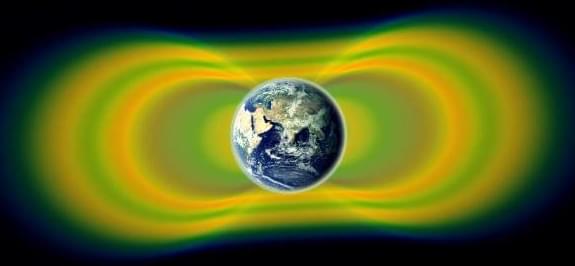

One of the great mysteries of modern science is dark matter. We know dark matter exists thanks to its effects on other objects in the cosmos, but we have never been able to directly see it. And it’s no minor thing—currently, scientists think it makes up about 85% of all the mass in the universe.

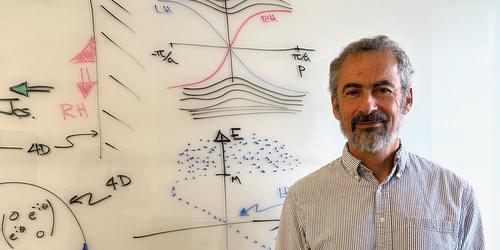

A new experiment by a collaboration led by the University of Chicago and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, known as the Broadband Reflector Experiment for Axion Detection or BREAD, has released its first results in the search for dark matter in a study published in Physical Review Letters. Though they did not find dark matter, they narrowed the constraints for where it might be and demonstrated a unique approach that may speed up the search for the mysterious substance, at relatively little space and cost.