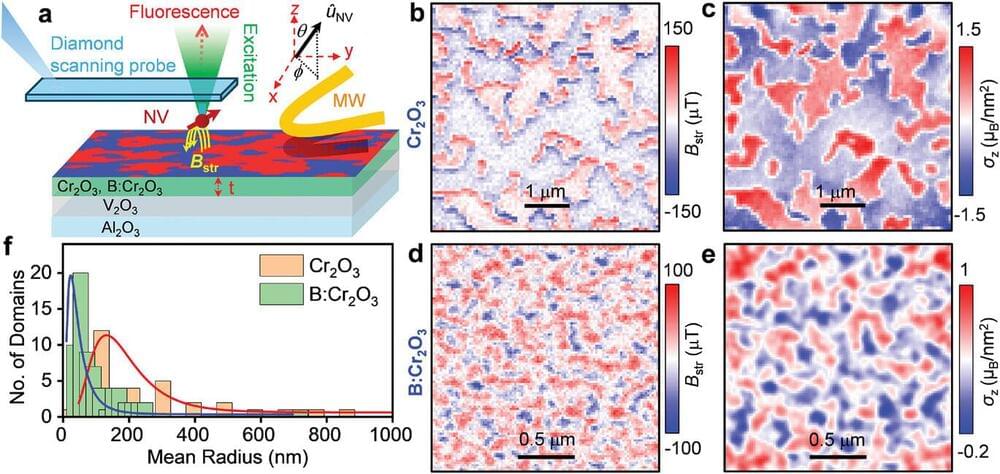

Results could aid understanding of how black holes produce vast intergalactic jets. Scientists have observed new details of how plasma interacts with magnetic fields, potentially providing insight into the formation of enormous plasma jets that stretch between the stars.

Whether between galaxies or within doughnut-shaped fusion devices known as tokamaks, the electrically charged fourth state of matter known as plasma regularly encounters powerful magnetic fields, changing shape and sloshing in space. Now, a new measurement technique using protons, subatomic particles that form the nuclei of atoms, has captured details of this sloshing for the first time, potentially providing insight into the formation of enormous plasma jets that stretch between the stars.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) created detailed pictures of a magnetic field bending outward because of the pressure created by expanding plasma. As the plasma pushed on the magnetic field, bubbling and frothing known as magneto-Rayleigh Taylor instabilities arose at the boundaries, creating structures resembling columns and mushrooms.