One of the leading theoretical physicists today talks about progress in understanding the open mysteries of the cosmos.

CU Boulder scientists have found how ions move in tiny pores, potentially improving energy storage in devices like supercapacitors. Their research updates Kirchhoff’s law, with significant implications for energy storage in vehicles and power grids.

Imagine if your dead laptop or phone could be charged in a minute, or if an electric car could be fully powered in just 10 minutes. While this isn’t possible yet, new research by a team of scientists at CU Boulder could potentially make these advances a reality.

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers in Ankur Gupta’s lab discovered how tiny charged particles, called ions, move within a complex network of minuscule pores. The breakthrough could lead to the development of more efficient energy storage devices, such as supercapacitors, said Gupta, an assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering.

Using a laser to raise the energy state of an atom ’s nucleus, known as excitation, can lead to the development of the most precise atomic clocks. This process has been challenging because the electrons surrounding the nucleus are highly reactive to light, necessitating more light to affect the nucleus. UCLA physicists have overcome this by bonding the electrons with fluorine in a transparent crystal, allowing them to excite the neutrons in a thorium atom’s nucleus using a moderate amount of laser light. This achievement paves the way for significantly more accurate measurements of time, gravity, and other fields, far surpassing the current accuracy levels provided by atomic electrons.

For almost half a century, physicists have envisioned the possibilities that could arise from elevating the energy state of an atom’s nucleus with a laser. This breakthrough would enable the replacement of current atomic clocks with a nuclear clock, the most accurate timekeeping device ever conceived. Such precision would revolutionize fields like deep space navigation and communication.

It would also allow scientists to measure precisely whether the fundamental constants of nature are, in fact, really constant or merely appear to be because we have not yet measured them precisely enough.

“We can rewind to a previous scene or skip several scenes ahead.”

An worldwide team of scientists claims to have found a means to speed up, slow down, and even reverse the clock of a given system by taking use of the peculiar qualities of the quantum universe, as reported by Spanish newspaper El País.

The scientists from the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the University of Vienna presented their findings in six separate papers. The basic principles of physics do not transfer intuitively onto the subatomic world, which is made up of quantum particles known as qubits, which can exist in several states at the same time, a phenomenon known as quantum entanglement.

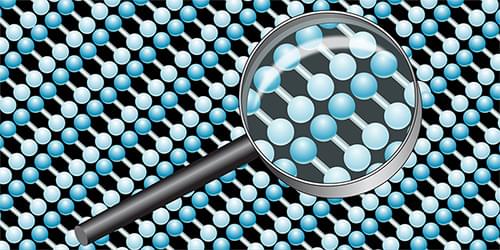

A discovery that uncovered the surprising way atoms arrange themselves and find their preferred neighbors in multi-principal element alloys (MPEA) could enable engineers to “tune” these unique and useful materials for enhanced performance in specific applications ranging from advanced power plants to aerospace technologies, according to the researchers who made the finding.

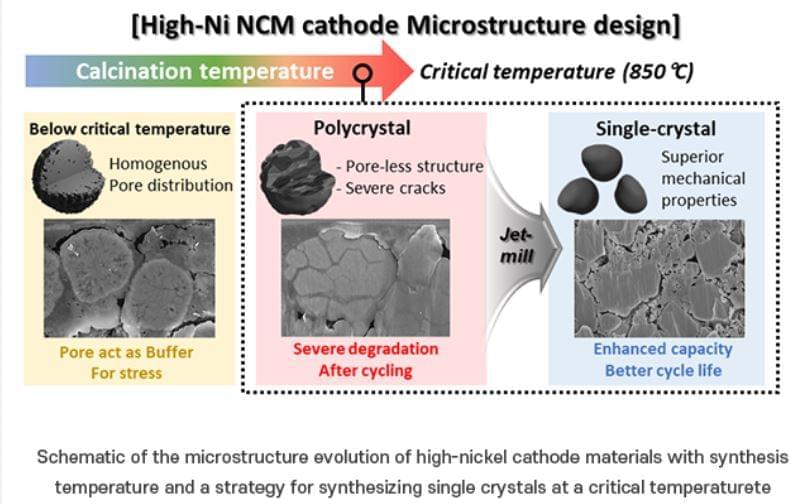

Lithium (Li) secondary batteries, commonly used in electric vehicles, store energy by converting electrical energy to chemical energy and generating electricity to release chemical energy to electrical energy through the movement of Li-ions between a cathode and an anode. These secondary batteries mainly use nickel (Ni) cathode materials due to their high lithium-ion storage capacity. Traditional nickel-based materials have a polycrystalline morphology composed of many tiny crystals which can undergo structural degradation during charging and discharging, significantly reducing their lifespan.

One approach to addressing this issue is to produce the cathode material in a “single-crystal” form. Creating nickel-based cathode materials as single large particles, or “single crystals,” can enhance their structural and chemical stability and durability. It is known that single-crystal materials are synthesized at high temperatures and become rigid. However, the exact process of hardening during synthesis and the specific conditions under which this occurs remain unclear.

To improve the durability of nickel cathode materials for electric vehicles, the researchers focused on identifying a specific temperature, referred to as the “critical temperature,” at which high-quality single-crystal materials are synthesized. They investigated various synthesis temperatures to determine the optimal conditions for forming single crystals in synthesis of a nickel-based cathode material (N884). The team systematically observed the impact of temperature on the material’s capacity and long-term performance.

An answer to a decades-old question in the theory of quantum entanglement raises more questions about this quirky phenomenon.

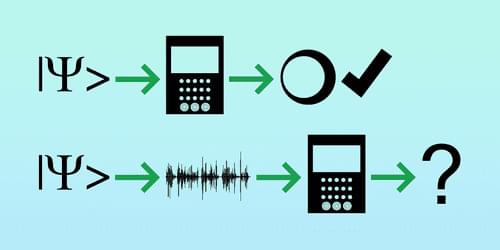

Physicists have a long list of open problems they consider important for advancing the field of quantum information. Problem 5 asks whether a system can exist in its maximally entangled state in a realistic scenario, in which noise is present. Now Julio de Vicente at Carlos III University of Madrid has answered this fundamental quantum question with a definitive “no” [1]. De Vicente says that he hopes his work will “open a new research avenue within entanglement theory.”

From quantum sensors to quantum computers, many technologies require quantum mechanically entangled particles to operate. The properties of such particles are correlated in a way that would not be possible in classical physics. Ideally, for technology applications, these particles should be in the so-called maximally entangled state, one in which all possible measures of entanglement are maximized. Scientists predict that particles can exist in this state in the absence of experimental, environmental, and statistical noise. But it was unclear whether the particles could also exist in a maximally entangled state in real-world scenarios, where noise is unavoidable.

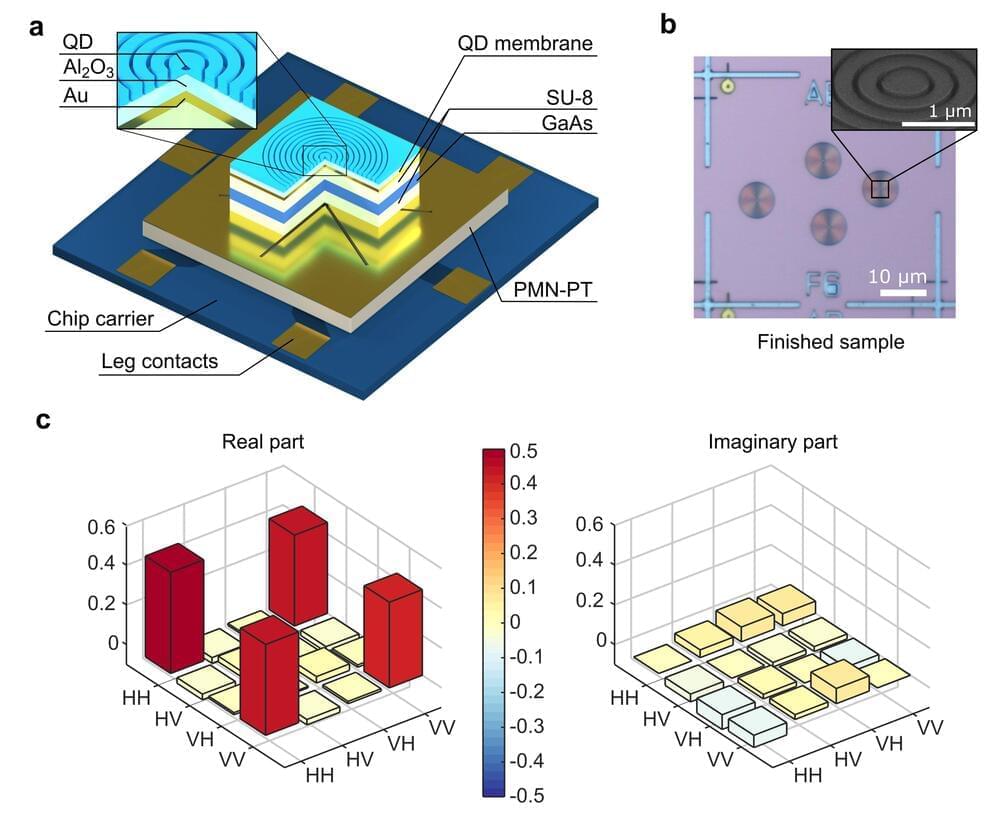

A new manipulation technique could enable the realization of more versatile quantum simulators.

The Born rule, formulated almost a century ago, says that measuring a system yields an outcome whose probability is determined by the wave-function amplitude. As if by magic, preparing a quantum system in the same way and performing the same measurement can produce different results. For a long time, the Born rule’s probabilistic nature was more of a theoretical concept. But with the advent of quantum simulators, it has become an experimental reality. So-called snapshots—different measurement outcomes of the same quantum many-body state—are routinely measured. In the case of cold atoms in optical lattices, such snapshots are images that show with single-site resolution whether an atom is present or not. Now Alexander Impertro of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and his collaborators have devised a way to take snapshots not just of atoms’ whereabouts but also of properties analogous to currents and local kinetic energy in crystals [1].

Contrary to widespread belief, our Moon does have an atmosphere, albeit extremely thin and officially known as an “exosphere”. But what are the processes responsible for forming and maintaining this exosphere, which have eluded scientists for some time? This is what a recent study published in Science Advances hopes to address as a team of researchers investigated how a phenomenon known as “impact vaporization” from the surface being hit my objects ranging from micrometeoroids to massive meteorites during its recent and ancient history, respectively. This study holds the potential to help scientists better understand the formation and evolution of planetary bodies throughout the solar system and the processes that maintain them today.

For the study, the team analyzed 10 Apollo lunar samples (one volcanic and nine lunar regolith aka “lunar soil”) collected by astronauts over five landing sites with the goal of ascertaining how much space weathering they’ve endured over the Moon’s long history. This is because when an impact occurs, this causes the specific atoms to vaporize and kick up portions of this material into space while other portions remain trapped by lunar gravity, although now orbiting the Moon. In the end, the researchers discovered that impact vaporization is the main process responsible for the lunar exosphere over the several billion-year history of the Moon.

“We give a definitive answer that meteorite impact vaporization is the dominant process that creates the lunar atmosphere,” said Dr. Nicole Nie, who is an assistant professor in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences and lead author of the study. “The moon is close to 4.5 billion years old, and through that time the surface has been continuously bombarded by meteorites. We show that eventually, a thin atmosphere reaches a steady state because it’s being continuously replenished by small impacts all over the moon.”