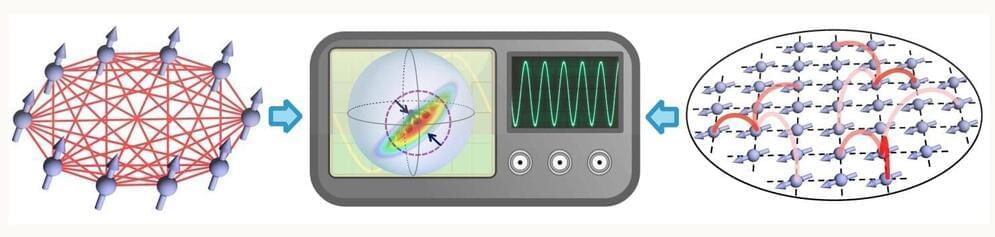

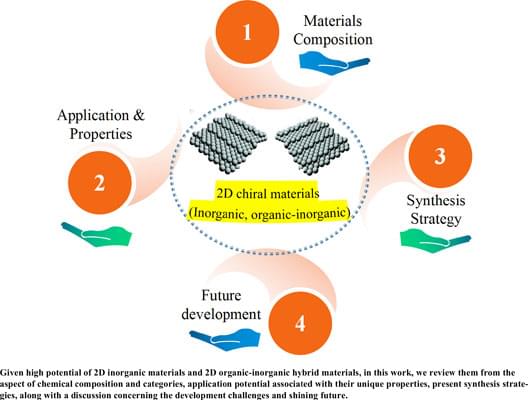

Recently, two-dimensional (2D) materials have gained immense attention, as they are promising in various application fields, such as energy storage, thermal management, photodetectors, catalysis, field-effect transistors, and photovoltaic modules. These merits of 2D materials are attributed to their unique structure and properties. Chirality is an intrinsic property of a substance, which means the substance can not overlap with its mirror image. Significant progress has been made in chiral science, for chirality uniquely influences a chiral substance’s performance. With the rapid development of chiral science, it became unveiled that chirality not only exists in chiral organic molecules but can also be induced in 2D inorganic materials and 2D organic-inorganic hybrid materials by breaking the chiral symmetry within their framework to form 2D chiral materials. Compared with 2D materials that do not have chirality, these 2D inorganic chiral materials and 2D organic-inorganic hybrid chiral materials exhibit innovative performance due to chiral symmetry breaking. Nevertheless, at present, only a fraction of work is available which comprehensively sums up the progress of these promising 2D chiral materials. Thus, given their high potential, it is urgent to summarize these newly developed 2D chiral materials comprehensively. In the current study, to feature and highlight their major significance, the recent progress of 2D inorganic materials and 2D organic-inorganic hybrid materials from their chemical composition and categories, application potential associated with their unique properties, and present synthesis strategies to fabricate them along with discussion concerning the development challenges and their bright future were reviewed. This review is anticipated to be instructive and provide a high understanding of advanced functional 2D materials with chirality.

Keywords: Chirality, two-dimensional, inorganic, organic-inorganic hybrid, asymmetric, enantioselective, chiral-induced spin selectivity (CISS), photoelectronic, spintronics.