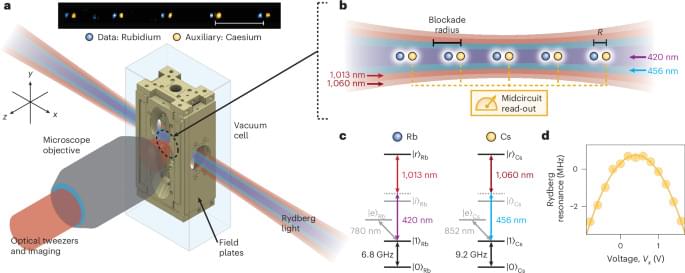

A new technology to continuously place individual atoms exactly where they are needed could lead to new materials for devices that address critical needs for the field of quantum computing and communication that cannot be produced by conventional means, say scientists who developed it.

A research team at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory created a novel advanced microscopy tool to “write” with atoms, placing those atoms exactly where they are needed to give a material new properties.

“By working at the atomic scale, we also work at the scale where quantum properties naturally emerge and persist,” said Stephen Jesse, a materials scientist who leads this research and heads the Nanomaterials Characterizations section at ORNL’s Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, or CNMS. “We aim to use this improved access to quantum behavior as a foundation for future devices that rely on uniquely quantum phenomena, like entanglement, for improving computers, creating more secure communications and enhancing the sensitivity of detectors.”