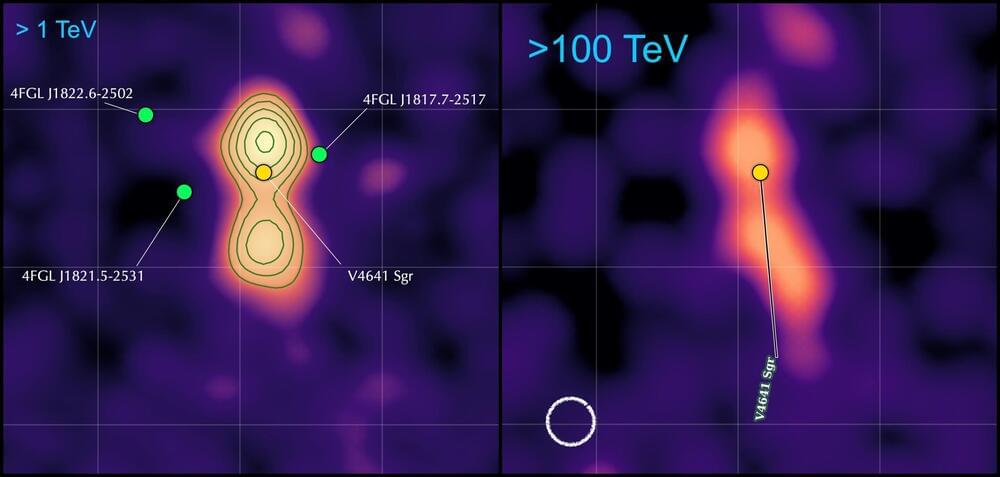

Electromagnetic radiation of extremely high energies is produced not only in the jets launched from active nuclei of distant galaxies, but also in jet-launching objects lying within the Milky Way, called microquasars. This latest finding by scientists from the international High-Altitude Water Cherenkov Gamma-Ray Observatory (HAWC) radically changes the previous understanding of the mechanisms responsible for the formation of ultra-high-energy cosmic radiation and in practice marks a revolution in its further study.

Since the discovery of cosmic radiation by Victor Hess in 1912, astronomers have believed that the celestial bodies responsible in our galaxy for the acceleration of these particles up to the highest energies are the remains of gigantic supernova explosions, called supernova remnants.

However, a different picture comes from the latest data from the HAWC observatory: The sources of radiation of extremely high energies turn out to be microquasars. Astrophysicists from the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IFJ PAN) in Cracow played a key role in the discovery.