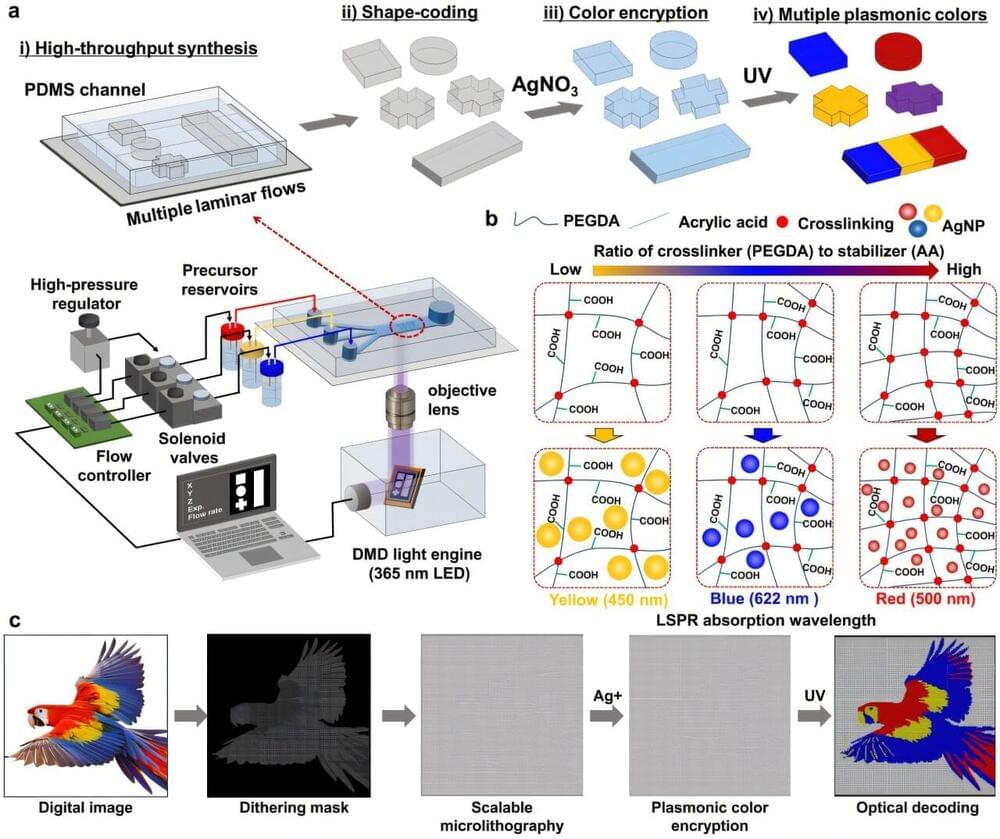

In a significant advancement in the field of anti-counterfeiting technology, Professor Jiseok Lee and his research team in the School of Energy and Chemical Engineering at UNIST have developed a new hidden anti-counterfeiting technology, harnessing the unique properties of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). The results are published in Advanced Materials.

“The technology we have developed holds significant promise in preventing the counterfeiting of valuable artworks and defense materials, particularly in scenarios where authenticity must be verified against potential piracy,” Professor Lee explained.

The team leveraged the inherent disadvantage of AgNPs, which tend to discolor upon exposure to UV light, to create a controlled color development process. By trapping silver nanoparticles within a polymer matrix, researchers can manipulate particle size and, consequently, the color emitted under UV light. Larger polymer nets yield silver nanoparticles that appear yellow, while smaller nets produce a red hue, allowing for precise control of the resultant colors based on ingredient combinations.