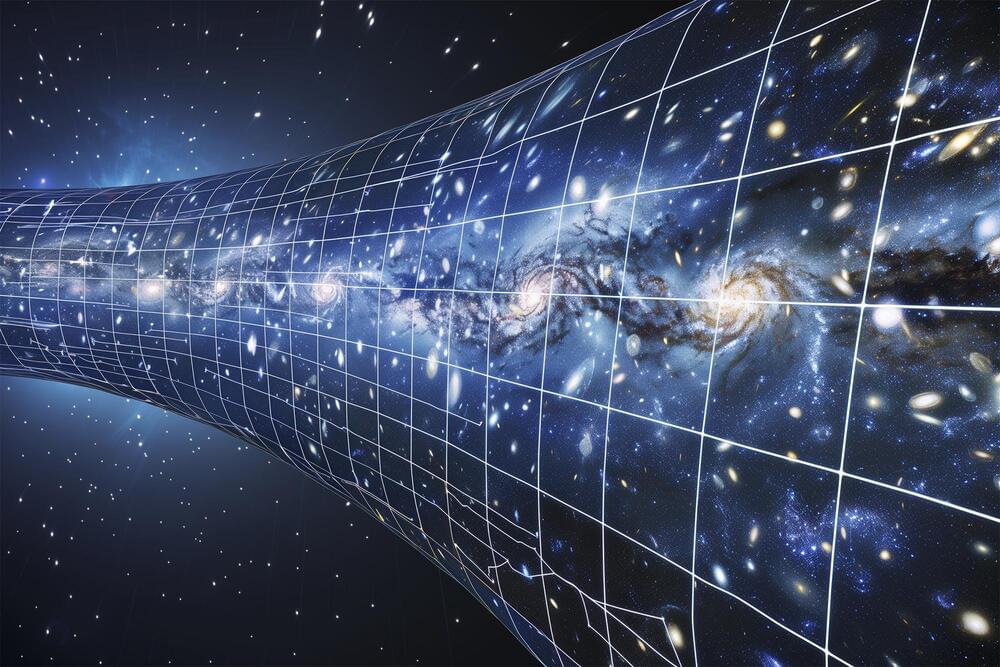

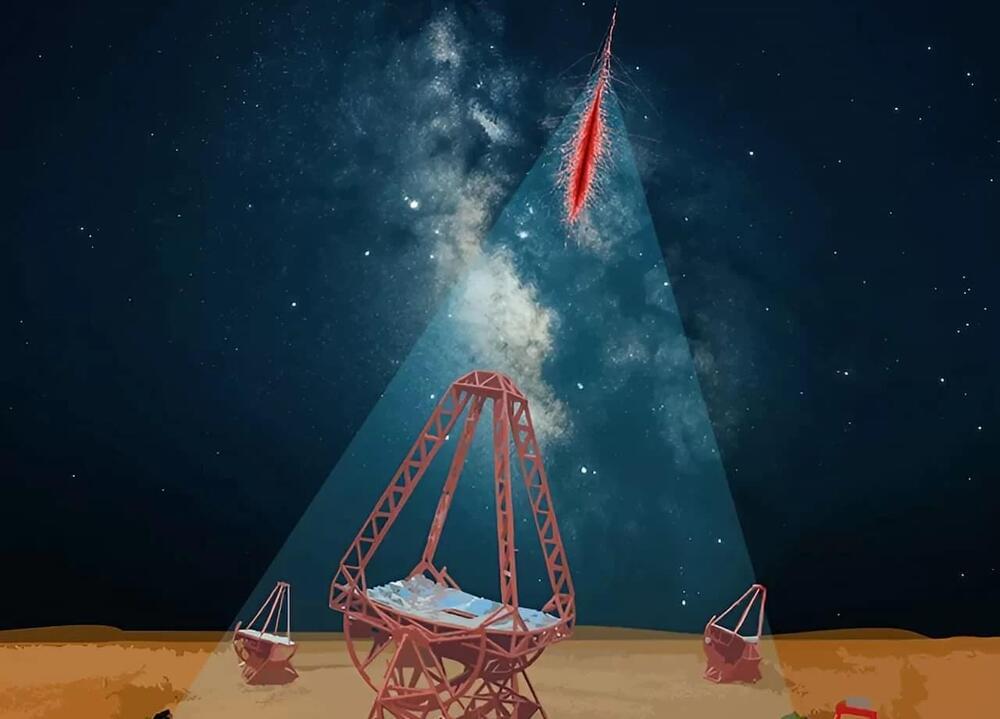

The universe is a stage filled with extreme phenomena, where temperatures and energies reach unimaginable levels. In this context, there are objects such as supernova remnants, pulsars, and active galactic nuclei that generate charged particles and gamma rays with energies far exceeding those involved in nuclear processes like fusion within stars. These particles, as direct witnesses of extreme cosmic processes, offer key insights into the workings of the universe.

Gamma rays, for instance, have the ability to traverse space without being altered, providing direct information about their sources of origin. However, charged particles, known as cosmic rays, face a more complex journey. When interacting with the omnipresent magnetic fields of the cosmos, these particles are deflected and lose part of their energy, especially high-energy electrons and positrons, referred to as cosmic-ray electrons (CRe). With energies surpassing one teraelectronvolt (TeV)—a thousand times more than visible light— these particles gradually fade away, complicating the identification of their point of origin.

Detecting high-energy particles such as CRe is a monumental task. Space instruments, with their limited detection areas, fail to capture sufficient particles at these extreme energies. On the other hand, ground-based observatories face an additional challenge: distinguishing particle cascades triggered by cosmic-ray electrons from the far more frequent ones generated by protons and heavier cosmic-ray nuclei.