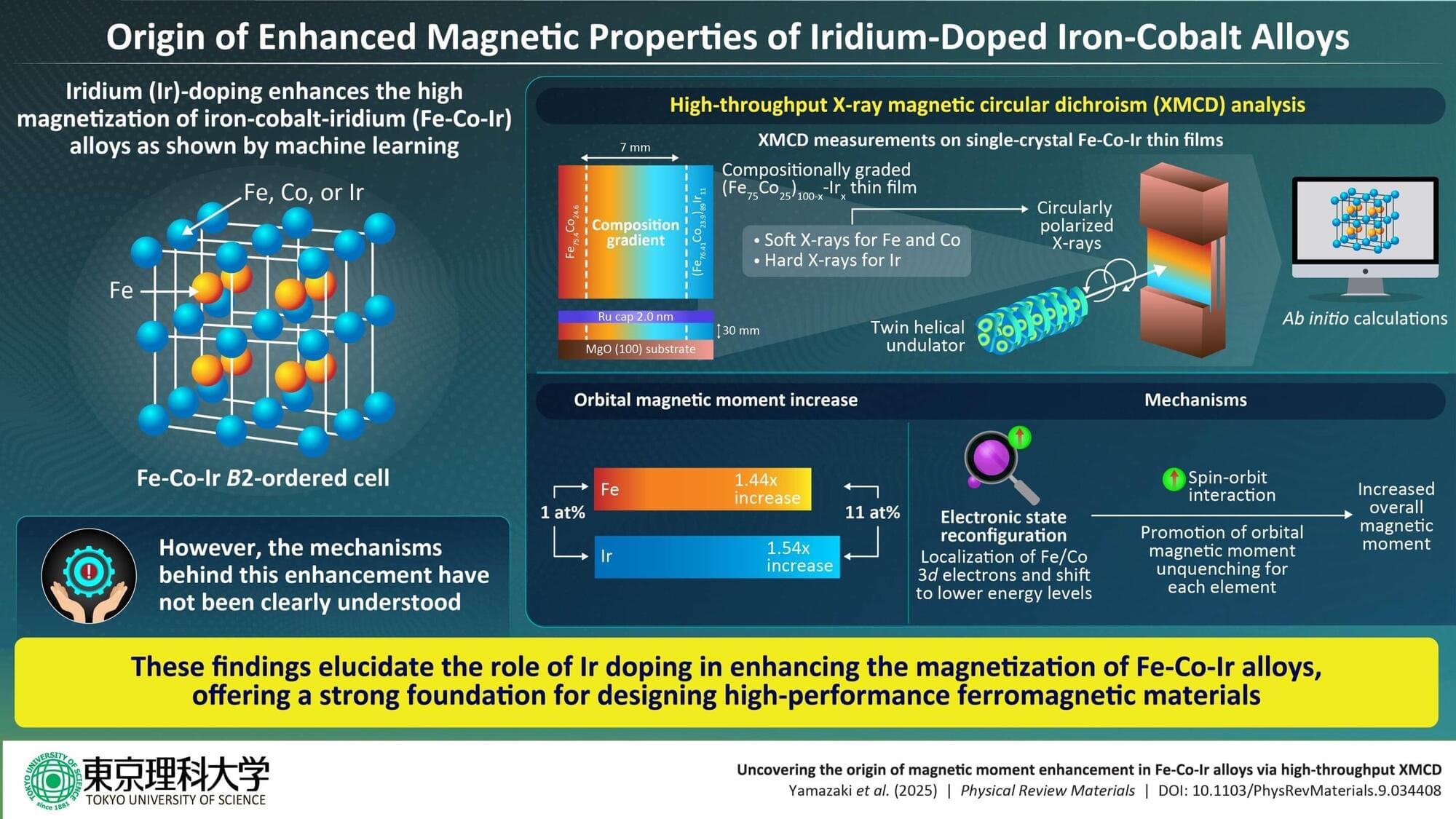

Magnetic materials have become indispensable to various technologies that support our modern society, such as data storage devices, electric motors, and magnetic sensors.

High-magnetization ferromagnets are especially important for the development of next-generation spintronics, sensors, and high-density data storage technologies. Among these materials, the iron-cobalt (Fe-Co) alloy is widely used due to its strong magnetic properties. However, there is a limit to how much their performance can be improved, necessitating a new approach.

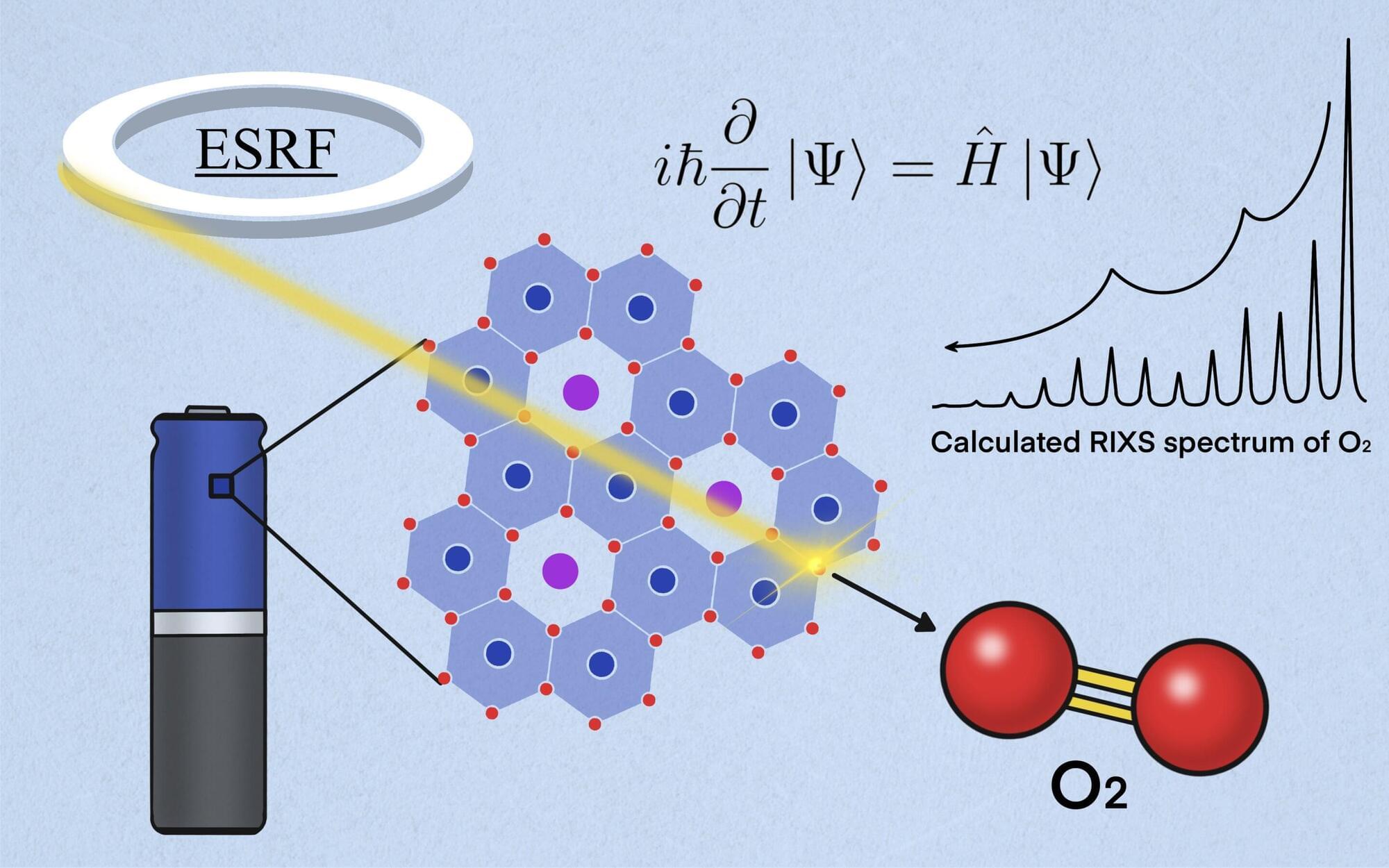

Some earlier studies have shown that epitaxially grown films made up of Fe-Co alloys doped with heavier elements exhibit remarkably high magnetization. Moreover, recent advances in computational techniques, such as the integration of machine learning with ab initio calculations, have significantly accelerated the search for new material compositions.