Icebergs float on water because the underlying liquid water has a higher density than the iceberg. Liquid water itself has its highest density at 4°C—one of the so-called anomalies of water, i.e. properties of liquids that are rarely observed for other liquids.

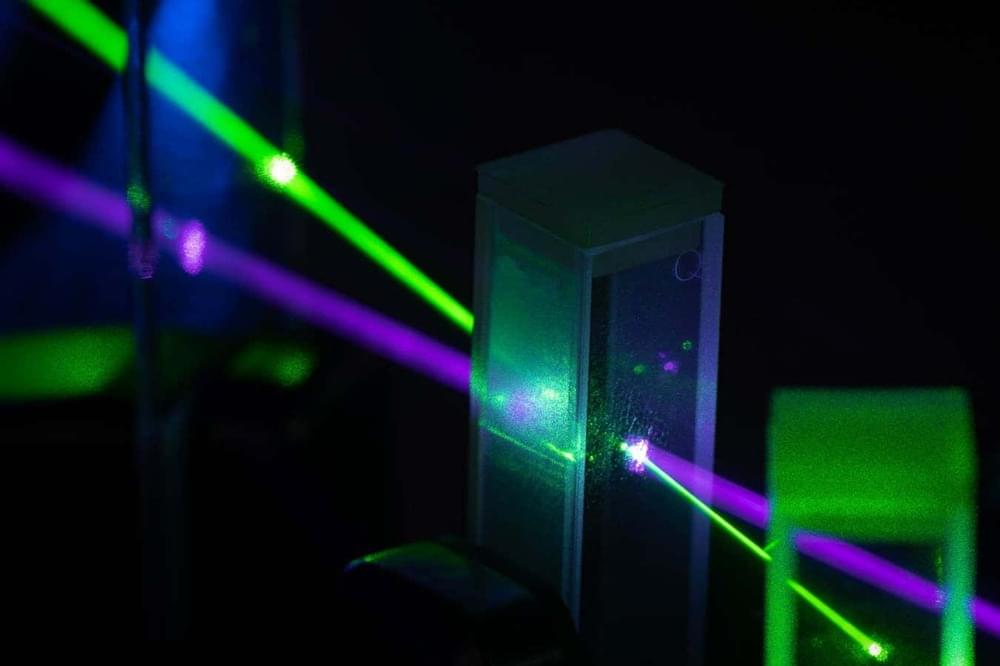

The origins of these anomalies have long been the subject of scientific research. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research have now discovered another piece to the puzzle to explain the special behavior of water.

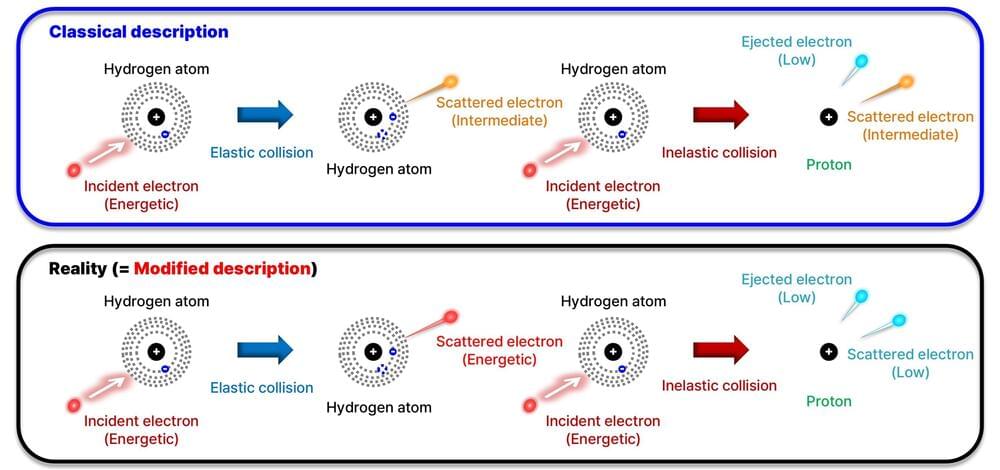

Many of the anomalous properties of water can be traced to the special interactions between the individual water molecules —the so-called hydrogen bonds. Each water molecule can donate two of these bonds—one from each hydrogen atom—and accept two of them from other, neighboring molecules.