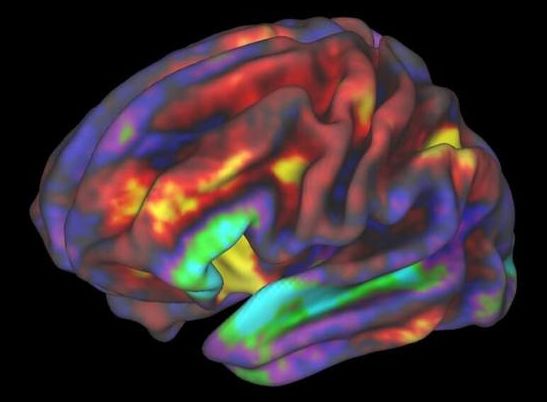

Scientists from 4 different Swiss universities describe how adhesion molecules activate autoaggressive immune cells and drive their infiltration in the nervous system in a model of multiple sclerosis.

Click to read the paper published in Frontiers in Immunology: https://fro.ntiers.in/tp1U

In experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model of multiple sclerosis (MS), myelin-specific T cells are activated in the periphery and differentiate in T helper (Th) 1 and Th17 effector cells, which cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to reach the central nervous system (CNS), where they induce neuroinflammation. Here, we explored the role of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and ICAM-2 in the activation of naïve myelin-specific T cells and in the subsequent migration of differentiated encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 cells across the BBB in vitro and in vivo. While on antigen-presenting cells ICAM-1, but not ICAM-2 was required for the activation of naïve CD4+ T cells, endothelial ICAM-1 and ICAM-2 mediated both Th1 and Th17 cell migration across the BBB. ICAM-1/-2-deficient mice developed ameliorated typical and atypical EAE transferred by encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 cells, respectively. Our study underscores important yet cell-specific contributions for ICAM-1 and ICAM-2 in EAE pathogenesis.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is considered an autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS). Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a prototypic animal model for MS, mimics many aspects of the acute inflammatory phase of the human disease (1). In EAE, naïve myelin-reactive CD4+ T cells are activated and differentiated in peripheral lymphoid tissue into encephalitogenic Th1 or Th17 cells, which travel in the blood circulation to the CNS. After crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB) they next infiltrate in the CNS parenchyma, leading to clinical manifestation of the disease (2). EAE can be actively induced by immunization with CNS myelin antigens emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant (aEAE) or by injection of myelin-reactive CD4+ T cells into syngeneic naïve recipients (tEAE) (3, 4).

Activation of naïve CD4+ T cells during aEAE occurs in the draining peripheral lymph nodes (dLNs), where T cells recognize their cognate antigen (Ag) on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) forming periodic contacts between the T-cell receptor (TCR) and the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)aa35−55 peptide loaded major histocompatibility complex (pMHC) on the APCs, referred to as the immunological synapse (IS) (5, 6). The fate of naïve T cells is determined within hours after Ag exposure by interacting with APCs in LN. The interaction between the integrin lymphocyte function associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) on the T cells and its ligand intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) on the APCs is suggested to be involved in modulating the IS. However, APCs additionally express ICAM-2, an alternate ligand of LFA-1.