Access to an online program that provides easily accessible, interactive, tailored healthy lifestyle and behavior change techniques is associated with better health-related quality of life among adult stroke survivors, according to new research from the University of Newcastle and Flinders University.

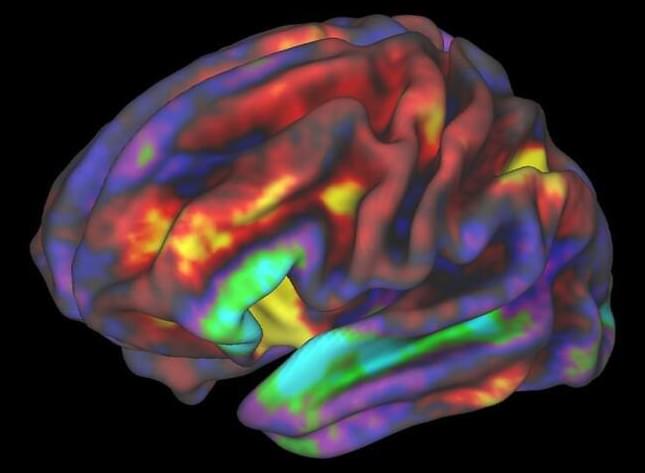

Stroke can lead to serious consequences for those that survive in terms of physical and cognitive disability. Improving lifestyle and health risk behaviors, including tobacco and alcohol use, physical activity, diet, depression, and anxiety, has the potential to significantly enhance stroke survivors’ quality of life.

Led by Dr. Ashleigh Guillaumier from the University of Newcastle and senior author Professor Billie Bonevski from Flinders University, the study, published in the journal PLOS Medicine, undertook a randomized control trial to evaluate the online program Prevent 2nd Stroke (P2S), which encourages users to set goals and monitor progress across various health risk areas.