Neuroscientist Matthew Sacchet is revealing how mastering meditation can not only enable transcendental states of bliss, but also reshape how we experience pain and emotion

Scientists have shown that brain connectivity patterns can predict mental functions across the entire brain. Each region has a unique “connectivity fingerprint” tied to its role in cognition, from language to memory. The strongest links were found in higher-level thinking skills that take years to develop. This work lays the groundwork for comparing healthy and disordered brains.

Depression is one of the most widespread mental health disorders worldwide, characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, a loss of interest in everyday activities, dysregulated sleep or eating patterns and other impairments. Some individuals diagnosed with depression also report being unable to pay attention during specific tasks, while also experiencing difficulties in planning and making decisions.

Recent studies have uncovered different biotypes of depression, subgroups of patients diagnosed with the condition that exhibit similar neural circuit patterns and behaviors. One of these subtypes is the so-called “cognitive biotype,” which is linked to a reduced ability to focus attention and inhibit distractions or unhelpful thinking patterns.

Researchers at Stanford University School of Medicine and the VA Palo Alto Health Care System recently carried out a study assessing the potential of guanfacine immediate release (GIR), a medication targeting neural processes known to be impaired in people with the cognitive biotype of depression.

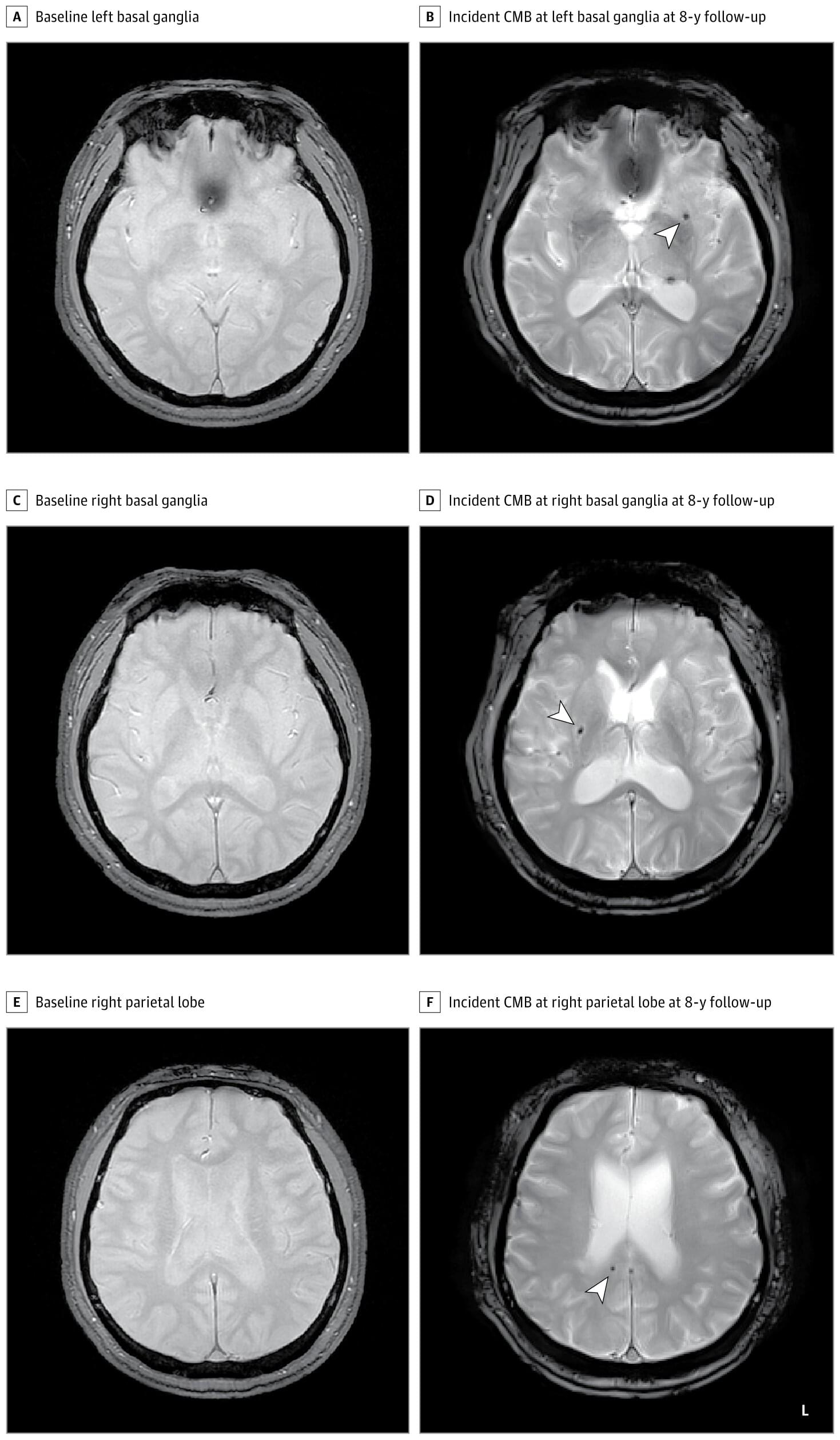

Research led by Korea University Ansan Hospital reports finding an association between moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea and increased risk of cerebral microbleeds.

Cerebral microbleeds appear as small lesions on MRI scans and are regarded as early markers of brain damage. Links with symptomatic stroke and dementia have been well documented, with prevalence ranging from 3% in middle age to 23% in older adults.

Known modifiable factors include smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and cardiocerebrovascular disease. Previous studies probing sleep apnea and microbleeds have yielded mixed results, suggesting the need for more comprehensive study.

Can you imagine someone in a mental health crisis—instead of calling a helpline—typing their desperate thoughts into an app window? This is happening more and more often in a world dominated by artificial intelligence. For many young people, a chatbot becomes the first confidant of emotions that can lead to tragedy. The question is: can artificial intelligence respond appropriately at all?

Researchers from Wroclaw Medical University decided to find out. They tested 29 popular apps that advertise themselves as mental health support. The results are alarming—not a single chatbot met the criteria for an adequate response to escalating suicidal risk.

The study is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Stereotypies are abnormal, repetitive, and seemingly goal-less behaviors that are prevalent within the animal kingdom. They have been documented in nearly every captive mammal and bird species, including laboratory animals, zoo animals, and farm animals.

In addition, they are a core feature of several human neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders such as autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia. Despite well documented environmental risk factors associated with stereotypies in captive animals, the developmental origins of these behaviors remain elusive.

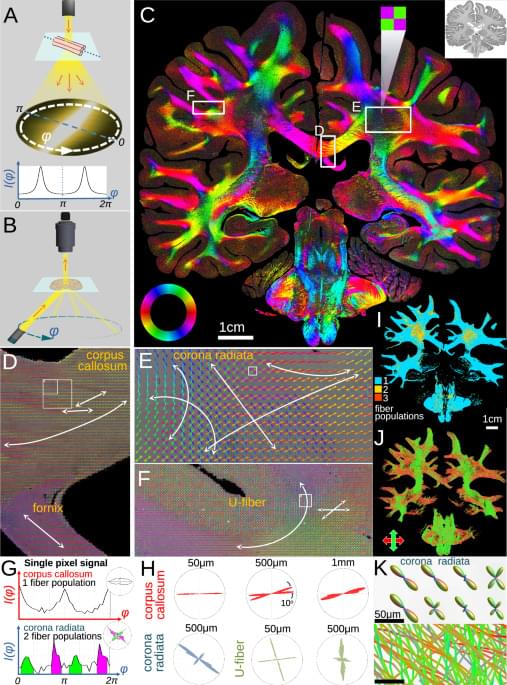

To understand brain diseases, neuroscientists try to understand the intricate maze of nerve fibers in our brains. For analysis under a microscope, brain tissue is often immersed in paraffin wax to create high-quality slices. But until now, it has been impossible to precisely trace the densely packed nerves in these slices. Researchers from Delft, Stanford, Jülich, and Rotterdam have achieved a milestone: using the ComSLI technique, they can now map the fibers in any tissue sample with micrometer precision. The research is published in Nature Communications.

Micron-resolution fiber mapping in histology independent of sample preparation.

Georgiadis and colleagues conduct micron-resolution fibre mapping on multiple histological tissue sections. Their light-scattering technique works across different sample preparations and tissue types, including formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded brain sections.