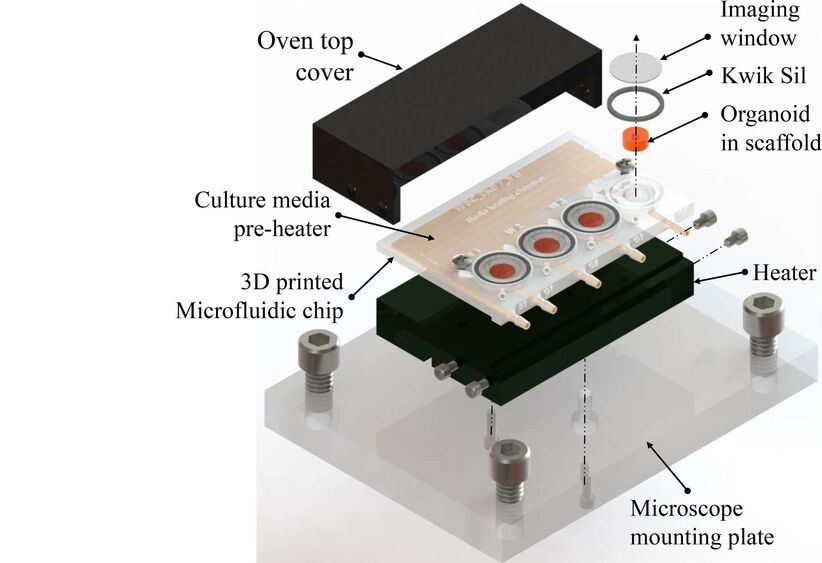

Scientists from MIT and the Indian Institute of Technology Madras have grown small amounts of self-organizing brain tissue, known as organoids, in a tiny 3D-printed system that allows observation while they grow and develop. The work is reported in Biomicrofluidics.

Current technology for real-time observation of growing organoids involves the use of commercial culture dishes with many wells in a glass-bottomed plate placed under a microscope. The plates are costly and only compatible with specific microscopes. They do not allow for the flow or replenishment of a nutrient medium to the growing tissue.

Recent advances have used a technique known as microfluidics, where a nutrient medium is delivered through small tubes connected to a tiny platform or chip. These microfluidic devices are, however, expensive and challenging to manufacture.