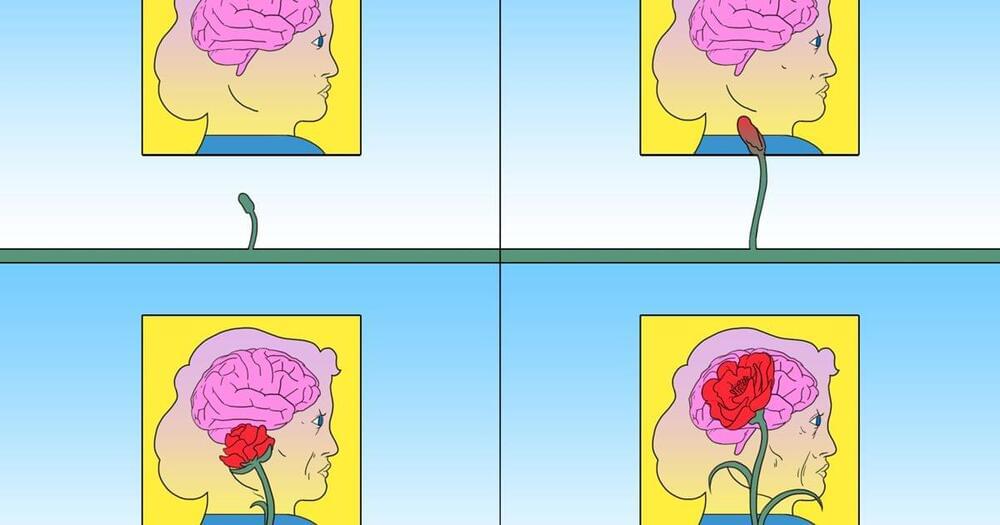

Almost everything we do relies on our sense of touch, from simple household chores to navigating potentially dangerous terrain. Scientists have long been curious about how the touch information we obtain with our hands and other parts of our bodies makes its way to the brain to generate the sensations we feel.

However, key aspects of touch, such as how the spinal cord and brainstem are involved in receiving, processing, and transmitting signals, remain unknown.

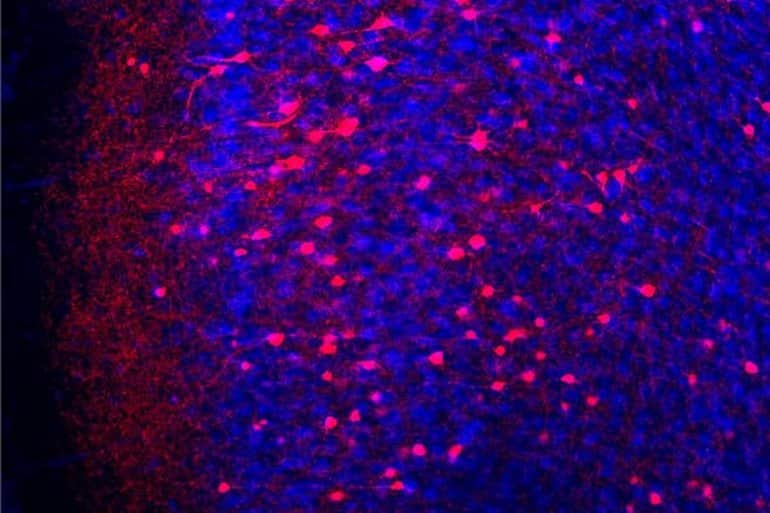

Now, two studies from Harvard Medical School researchers provide significant new understandings of how the spinal cord and brainstem contribute to the sense of touch.