The Brain Prize 2025 went to neuro-oncologists Michelle Monje and Frank Winkler for pioneering the field of cancer neuroscience.

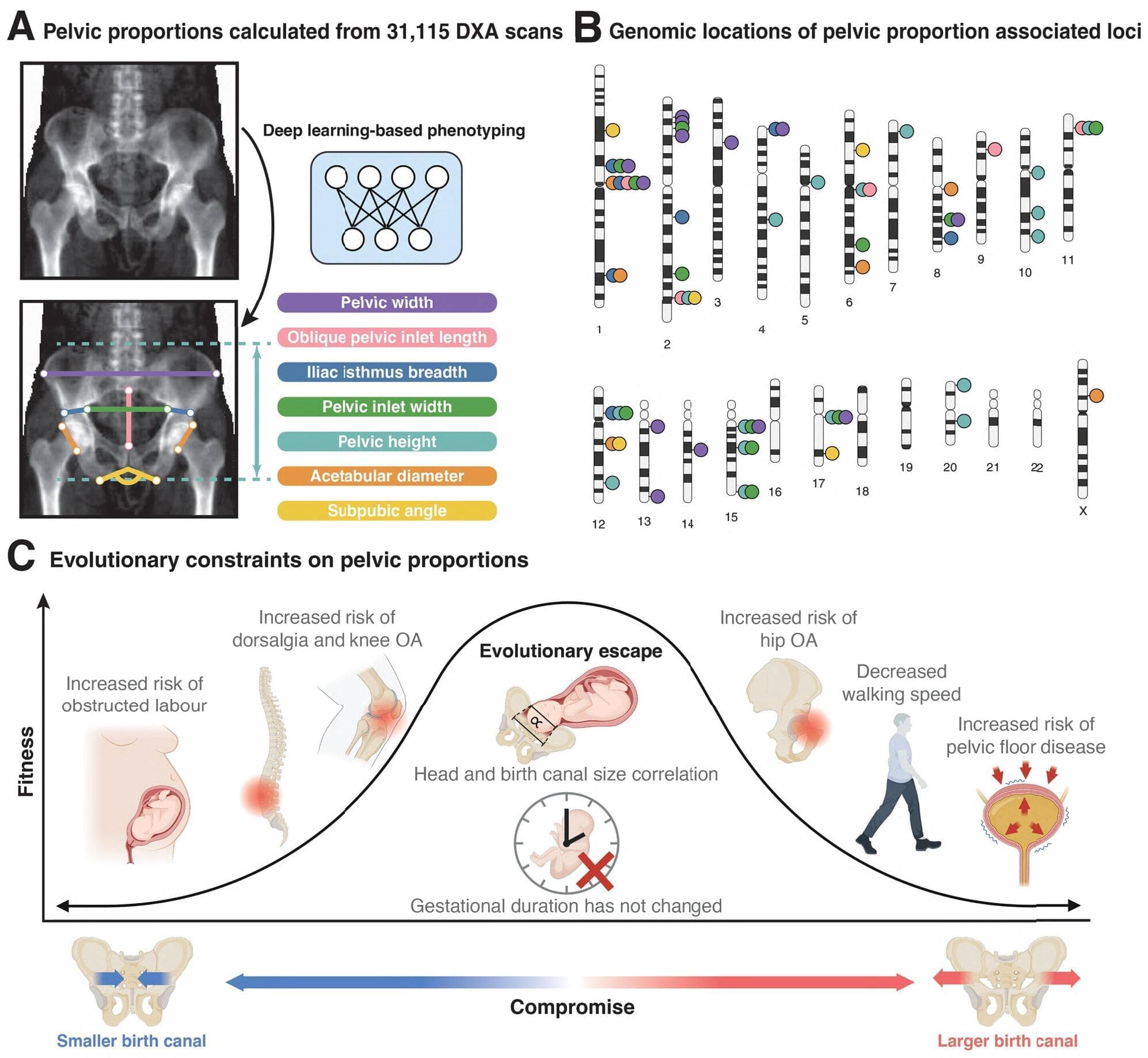

A team of integrative biologists at the University of Texas, Western Washington University and Columbia University Irving Medical Center has found that both wide and narrow hips provide women with certain physical benefits, though they both also have downsides. In their study published in the journal Science, the group compared hip structure among 31,000 people listed in the UK Biobank, with other physical features including those associated with pregnancy and birth.

For many years, evolutionary theorists have debated aspects of what has come to be known as the obstetrical dilemma. Prior research has shown that as humans evolved, their brains grew bigger. But prior research has also shown that as people began to walk upright, their hips grew narrower, creating a conundrum—wider hips are needed to deliver babies with bigger brains.

For this new study, the research team investigated the ways that nature has dealt with the obstetrical dilemma by studying hips and the pelvic floor.

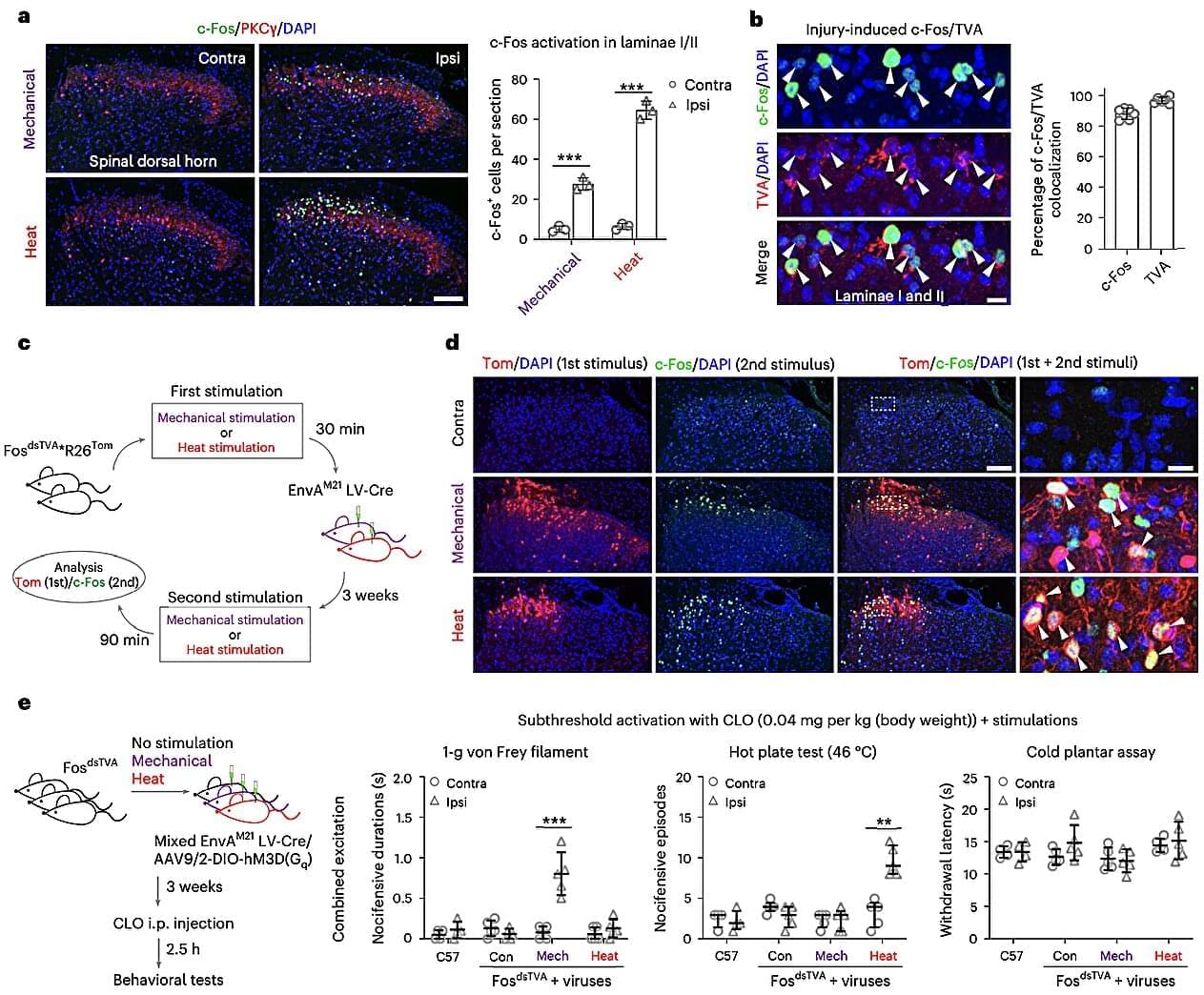

Humans and other animal species can experience many types of pain throughout the course of their lives, varying in intensity, unpleasantness and origin. Several past neuroscience studies have explored the neural underpinnings of pain, yet the processes supporting the ability to distinguish different types of physical pain are not fully understood.

In most vertebrates, painful sensations are known to arise from the nervous system, which includes the brain, an intricate network of nerves and the spinal cord. While the brain’s contribution to the encoding and processing of pain has been widely explored in the past, the role that neural circuits in the spinal cord play in the differentiation of physical pain remains unclear.

Researchers at Karolinska Institute, Uppsala University and other institutes recently carried out a study aimed at better understanding how networks of nerve cells in the spinal cord of adult mice contribute to the encoding of pain originating from exposure to heat and mechanical pain, which is caused by applied physical forces (e.g., pinches, cuts, etc.).

Changes in brain connectivity before and after puberty may explain why some children with a rare genetic disorder have a higher risk of developing autism or schizophrenia, according to a UCLA Health study.

Developmental psychiatric disorders like autism and schizophrenia are associated with changes in brain functional connectivity. However, the complexity of these conditions make it difficult to understand the underlying biological causes. By studying genetically defined brain disorders, researchers at UCLA Health and collaborators have shed light on possible mechanisms.

The UCLA study examined a particular genetic condition called chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome—caused by missing DNA on chromosome 22—which is associated with a higher risk of developing neuropsychiatric conditions such as autism and schizophrenia. But the underlying biological basis of this association has not been well understood.

A surprising link between the immune system and brain behavior is emerging, as new research reveals how a single immune molecule can affect both anxiety and sociability depending on which brain region it acts upon.

Scientists found that IL-17 behaves almost like a brain chemical, influencing neuron activity in ways that alter mood and behavior during illness. These findings suggest the immune system plays a much deeper role in shaping our mental states than previously thought, opening new doors for treating conditions like autism and anxiety through immune-based therapies.

Immune Molecules and Brain Behavior.

Pediatric neuroimmune disorders comprise a heterogeneous group of immune-mediated CNS inflammatory conditions. Some, such as multiple sclerosis, are well defined by validated diagnostic criteria. Others, such as anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, can be diagnosed with detection of specific autoantibodies. This review addresses neuroimmune disorders that neither feature a diagnosis-defining autoantibody nor meet criteria for a distinct clinicopathologic entity. A broad differential in these cases should include CNS infection, noninflammatory genetic disorders, toxic exposures, metabolic disturbances, and primary psychiatric disorders. Neuroimmune considerations addressed in this review include seronegative autoimmune encephalitis, seronegative demyelinating disorders such as neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, and genetic disorders of immune dysregulation or secondary neuroinflammation.

Depression among young people (aged 18–29 years) transitioning to adulthood is becoming more widespread. Knowing which factors in which systems co-enable resilience to depression is crucial, but there is no comprehensive synthesis of the physiological, psychological, social, economic, institutional, cultural, and environmental system factors associated with no or minimal emerging adult depression, or combinations of these factors. We have therefore conducted a preregistered systematic review (Prospero, CRD42023440153).

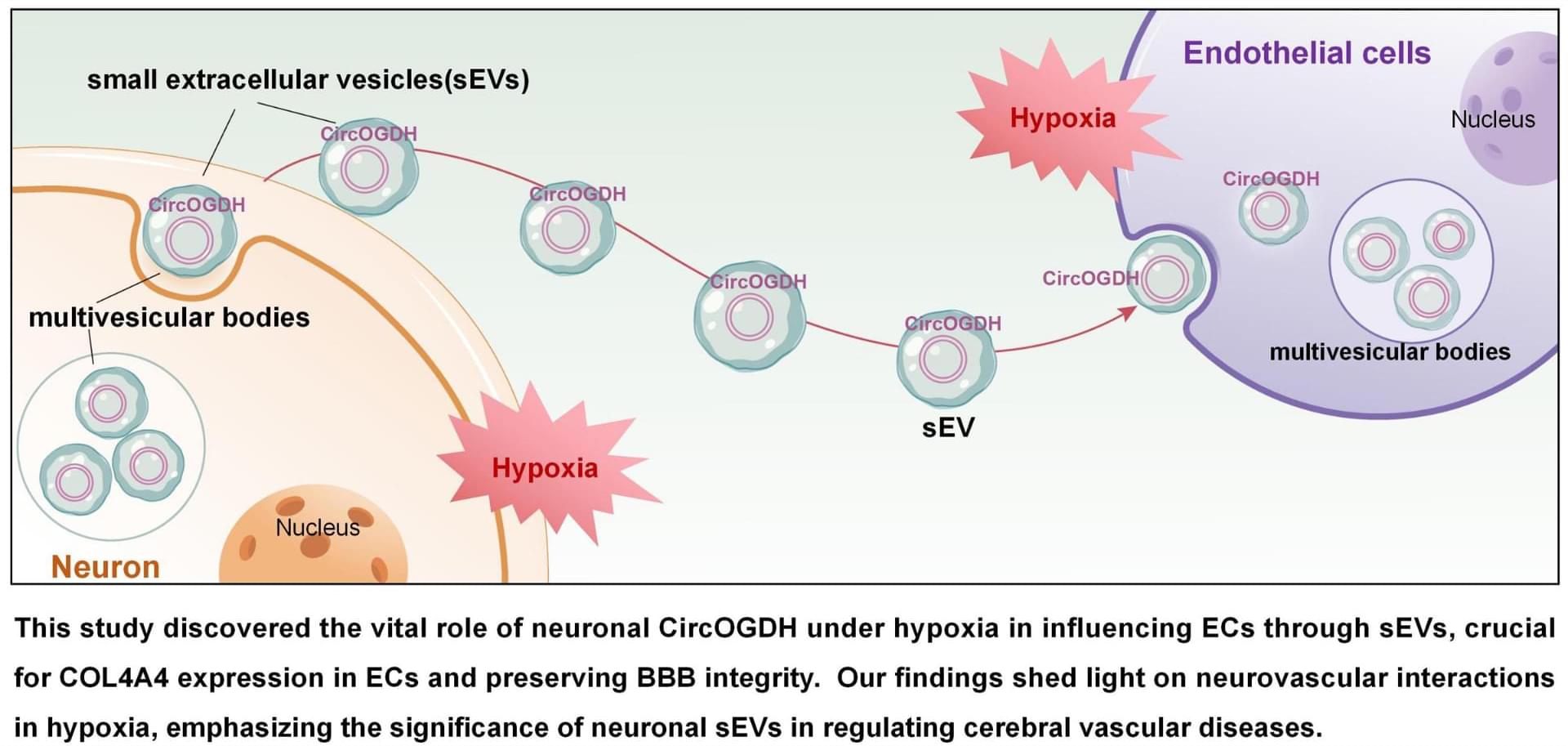

STROKE: Hypoxia induces neuronal release of CircOGDH in small extracellular vesicles to interact with endothelial cells for enhancing blood-brain barrier repair during acute ischemic stroke.

BACKGROUND: Acute ischemic stroke disrupts communication between neurons and blood vessels in penumbral areas. How neurons and blood vessels cooperate to achieve blood-brain barrier repair remains unclear. Here, we reveal crosstalk between ischemic penumbral neurons and endothelial cells (ECs) mediated by circular RNA originating from oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (CircOGDH). METHODS: We analyzed clinical data from patients with acute ischemic stroke to explore the relationship between CircOGDH levels and hemorrhagic transformation events. In addition, a middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion mouse model with neuronal CircOGDH suppression was used to assess endothelial permeability.