#neuroscience #biology #artificialintelligence #phenomenology #science In Philosophy Babble — The Great Minds SeriesIn this instal…

Category: neuroscience – Page 185

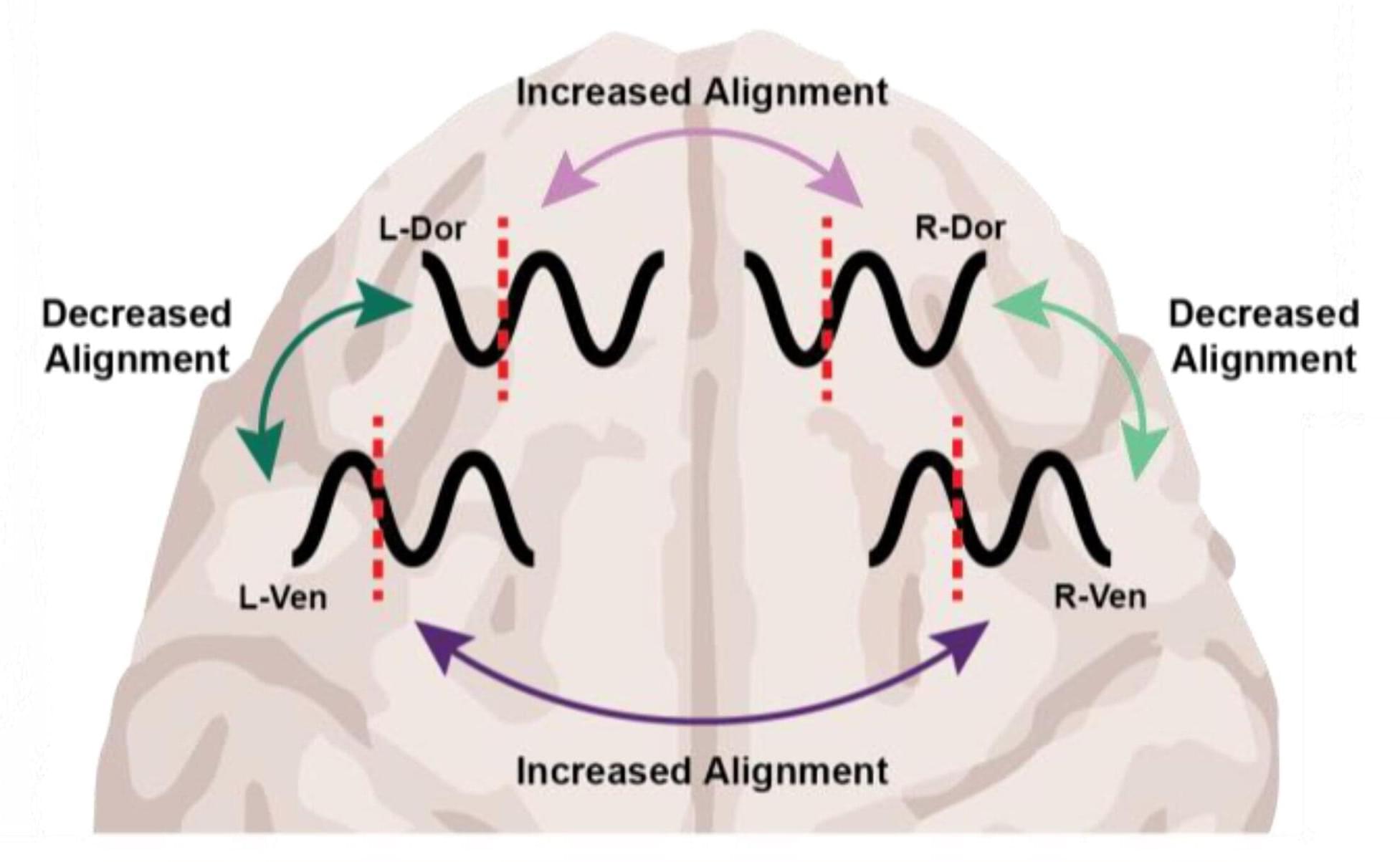

Different anesthetics, same result: Unconsciousness by shifting brainwave phase

At the level of molecules and cells, ketamine and dexmedetomidine work very differently, but in the operating room they do the same exact thing: anesthetize the patient. By demonstrating how these distinct drugs achieve the same result, a new study in animals by neuroscientists at The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT identifies a potential signature of unconsciousness that is readily measurable to improve anesthesiology care.

What the two drugs have in common, the researchers discovered, is the way they push around brain waves, which are produced by the collective electrical activity of neurons.

When brain waves are in phase, meaning the peaks and valleys of the waves are aligned, local groups of neurons in the brain’s cortex can share information to produce conscious cognitive functions such as attention, perception and reasoning, said Picower Professor Earl K. Miller, senior author of the new study in Cell Reports. When brain waves fall out of phase, local communications, and therefore functions, fall apart, producing unconsciousness.

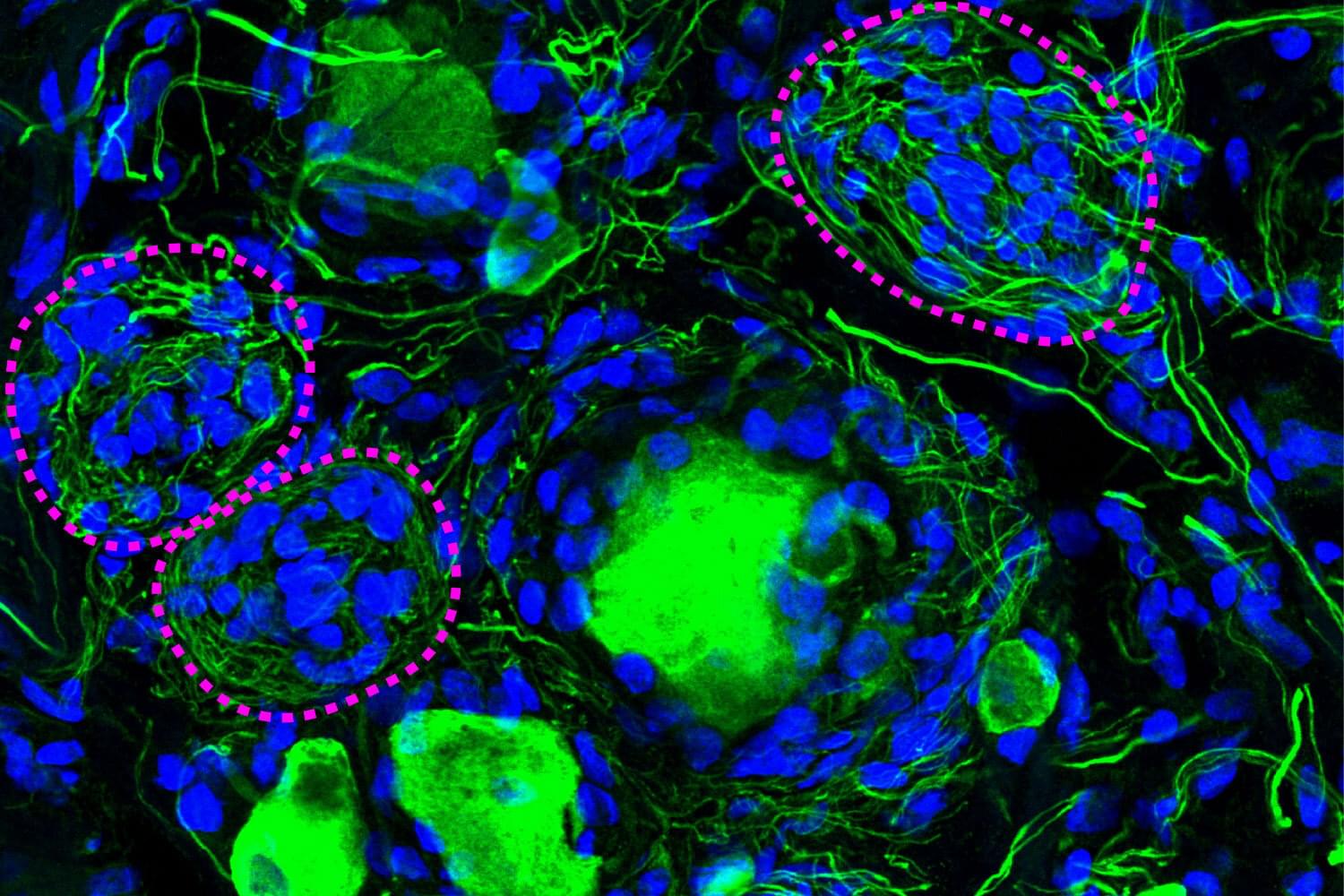

Forgotten cell clusters may hold key to diabetic neuropathy pain

A phenomenon largely ignored since its discovery 100 years ago appears to be a crucial component of diabetic pain, according to new research from The University of Texas at Dallas’s Center for Advanced Pain Studies (CAPS).

Findings from a new study published in Nature Communications suggest that cell clusters called Nageotte nodules are a strong indicator of nerve cell death in human sensory ganglia. These could prove to be a target for drugs that would protect these nerves or help manage diabetic neuropathy.

“The key finding of our study is really a new view of diabetic neuropathic pain,” said Dr. Ted Price, Ashbel Smith Professor of neuroscience in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, CAPS director and co-corresponding author of the study. “We believe our data demonstrate that neurodegeneration in the dorsal root ganglion is a critical facet of the disease—which should really force us to think about the disease in a new and urgent way.”

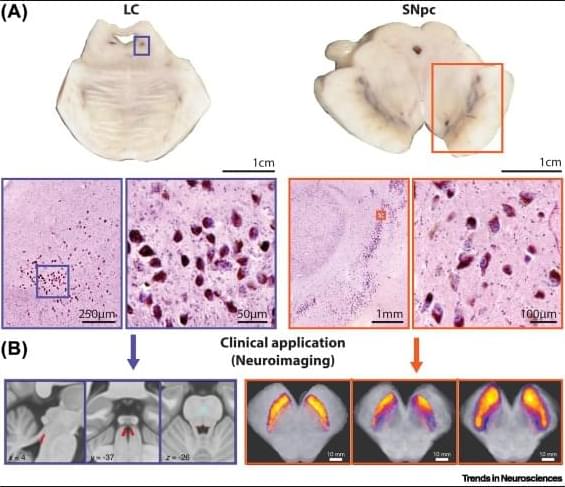

Neuromelanin and selective neuronal vulnerability to Parkinson’s disease

Neuromelanin is a unique pigment made by some human catecholamine neurons. These neurons survive with their neuromelanin content for a lifetime but can also be affected by age-related neurodegenerative conditions, as observed using new neuromelanin imaging techniques. The limited quantities of neuromelanin has made understanding its normal biology difficult, but recent rodent and primate models, as well as omics studies, have confirmed its importance for selective neuronal loss in Parkinson’s disease (PD). We review the development of neuromelanin in dopamine versus noradrenaline neurons and focus on previously overlooked cellular organelles in neuromelanin formation and function. We discuss the role of neuromelanin in stimulating endogenous α-synuclein misfolding in PD which renders neuromelanin granules vulnerable, and can exacerbates other pathogenic processes.

Beyond Darwin: Rethinking Evolution: Cooperation, Consciousness & Challenging Survival of the Fittest

Dive deep into the fascinating world of evolution, but this time, we’re going way beyond the basics of Darwinism! We explore alternative theories that challenge the traditional view of \.

From Blockchain to Brainwaves: Coinbase Co-Founder Fred Ehrsam Enters the Neurotech Race with Non-Invasive BCI Startup Nudge

Fred Ehrsam, billionaire co-founder of Coinbase, is shifting his next big bet from cryptocurrency to the human brain, unveiling a non-invasive brain-computer interface designed to modulate brain activity with sound waves.

Ehrsam’s entry as the latest competitor to join the race to develop accessible brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) follows similar recent efforts from tech leaders like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Bill Gates.

On April 8, Ehrsam’s startup, Nudge, unveiled its first product, the Nudge Zero. A noninvasive brain interface device that uses ultrasound to modulate brain activity, the technology represents the first start-up venture to pursue this unique approach with BCI technology.

Drug to slow Alzheimer’s well tolerated outside of clinical trial setting, study finds

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval in 2023 of lecanemab—a novel Alzheimer’s therapy shown in clinical trials to modestly slow disease progression—was met with enthusiasm by many in the field as it represented the first medication of its kind able to influence the disease. But side effects—brain swelling and bleeding—emerged during clinical trials that have left some patients and physicians hesitant about the treatment.

Medications can have somewhat different effects once they are released into the real world with broader demographics. Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis set out to study the adverse events associated with lecanemab treatment in their clinic patients and found that significant adverse events were rare and manageable.

Consistent with the results from carefully controlled clinical trials, researchers found that only 1% of patients experienced severe side effects that required hospitalization.

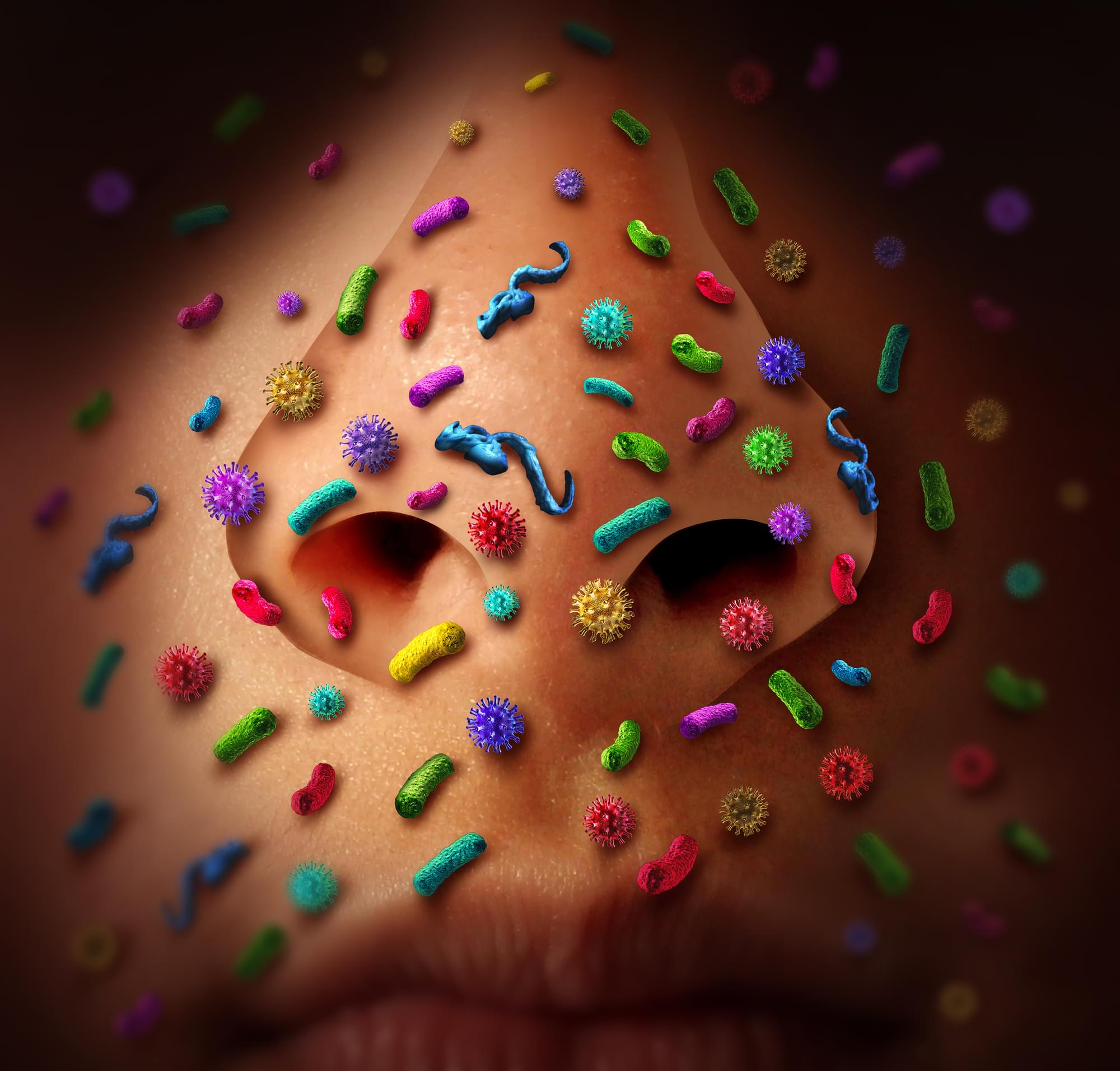

Bacteria could travel from the nose to the brain and trigger Alzheimer’s

Researchers in Australia have found evidence that bacteria that live in the nose can make their way into the brain through nasal cavity nerves, setting off a series of events that could lead to Alzheimer’s disease. The work adds to the growing body of evidence that Alzheimer’s may be initially triggered through viral or bacterial infections.

Chlamydia pneumoniae is a common bacterium that, as its name suggests, is a major cause of pneumonia, as well as a range of other respiratory diseases. But worryingly, it’s also been detected in the brain on occasion, indicating it could cause more insidious issues.

For the new study, researchers at Griffith University and the Queensland University of Technology set out to investigate how C. pneumoniae might get into the brain, and whether it could cause damage once there. The team already had an inkling about how this nose-dwelling bug might make the trek.