An EEG signal of sleep is associated with better performance on a mental task.

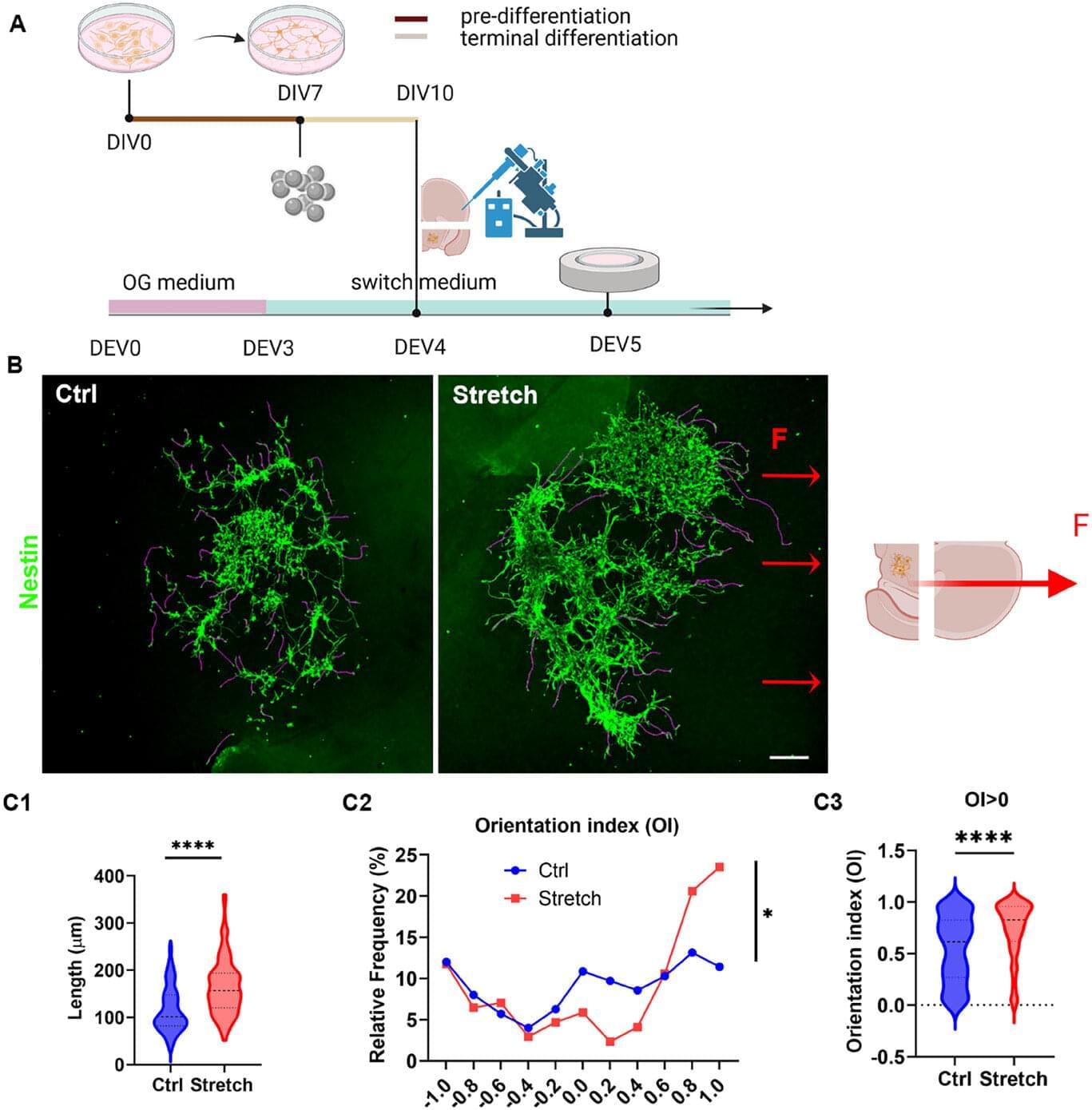

A collaborative study led by Professor Vittoria Raffa at the University of Pisa and Assistant Professor Fabian Raudzus (Department of Clinical Application) has unveiled a novel approach that uses magnetically guided mechanical forces to direct axonal growth, aiming to enhance the effectiveness of stem cell-based therapies for Parkinson’s disease (PD) and other neurological conditions.

Parkinson’s disease is characterized by the progressive degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (SN), which project to the striatum (ST) via the nigrostriatal pathway. The loss of these connections leads to dopamine deficiency and the onset of motor symptoms.

While cell replacement therapies using human stem cell-derived dopaminergic progenitors have shown encouraging results in clinical trials, a key limitation remains: the inability to guide the axons of transplanted cells over long distances to their appropriate targets in the adult brain.

Though it’s now clear humans continue to grow new brain cells throughout their entire lives, debate persists over whether this applies to specific areas involved with memory.

Previous studies have made the case for and against the existence of neurogenesis in hippocampus beyond childhood. A new study now offers some of the clearest evidence yet that this crucial memory-forming region does form fresh neurons well into adulthood.

The study is the work of researchers from the Karolinska Institute and the Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, and looks specifically at the dentate gyrus section of the hippocampus, the part of the brain that acts as a key control center for emotions, learning, and storing episodic memories.

A common diabetes drug may be the next big thing for migraine relief. In a clinical study, obese patients with chronic migraines who took liraglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, experienced over 50% fewer headache days and significantly improved daily functioning without meaningful weight loss. Researchers believe the drugs ability to lower brain fluid pressure is the key, potentially opening a completely new way to treat migraines. The effects were fast, sustained, and came with only mild side effects.

A diabetes medication that lowers brain fluid pressure has cut monthly migraine days by more than half, according to a new study presented today at the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) Congress 2025.

Researchers at the Headache Center of the University of Naples “Federico II” gave the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist liraglutide to 26 adults with obesity and chronic migraine (defined as ≥15 headache days per month). Patients reported an average of 11 fewer headache days per month, while disability scores on the Migraine Disability Assessment Test dropped by 35 points, indicating a clinically meaningful improvement in work, study, and social functioning.

Scientists at the University of Sydney have uncovered a malfunctioning version of the SOD1 protein that clumps inside brain cells and fuels Parkinson’s disease. In mouse models, restoring the protein’s function with a targeted copper supplement dramatically rescued movement, hinting at a future therapy that could slow or halt the disease in people.

To try everything Brilliant has to offer—free—for a full 30 days, visit https://brilliant.org/ArtemKirsanov. You’ll also get 20% off an annual premium subscription.

Socials:

X/Twitter: https://twitter.com/ArtemKRSV

Patreon: https://patreon.com/artemkirsanov.

My name is Artem, I’m a graduate student at NYU Center for Neural Science and researcher at Flatiron Institute. In this video we explore a recent study published in Science, which revealed that different compartments of pyramidal neurons (apical vs basal dendrites) use different plasticity rules for learning.

Link to the paper:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.ads4706

Outline:

00:00 Introduction.

01:23 Synaptic transmission.

06:09 Molecular machinery of LTP

08:40 Hebbian plasticity.

11:21 Non-Hebbian plasticity.

12:51 Hypothesis.

14:42 Experimental methods.

17:10 Result: compartmentalized plasticity.

19:30 Interpretation.

22:01 Brilliant.

23:08 Outro.

Music by Artlist.

A Conversation between Robert Lawrence Kuhn and Àlex Gómez-Marín.

The conversation will explore “a landscape of consciousness”, toward a taxonomy of explanations and implications.

In 2024, Àlex will curate and host conversations to address The Future Mind, seeking to gain clarity and insight into important contemporary matters that require both urgent action as well as deep reflection.

Recorded January 31, 2024

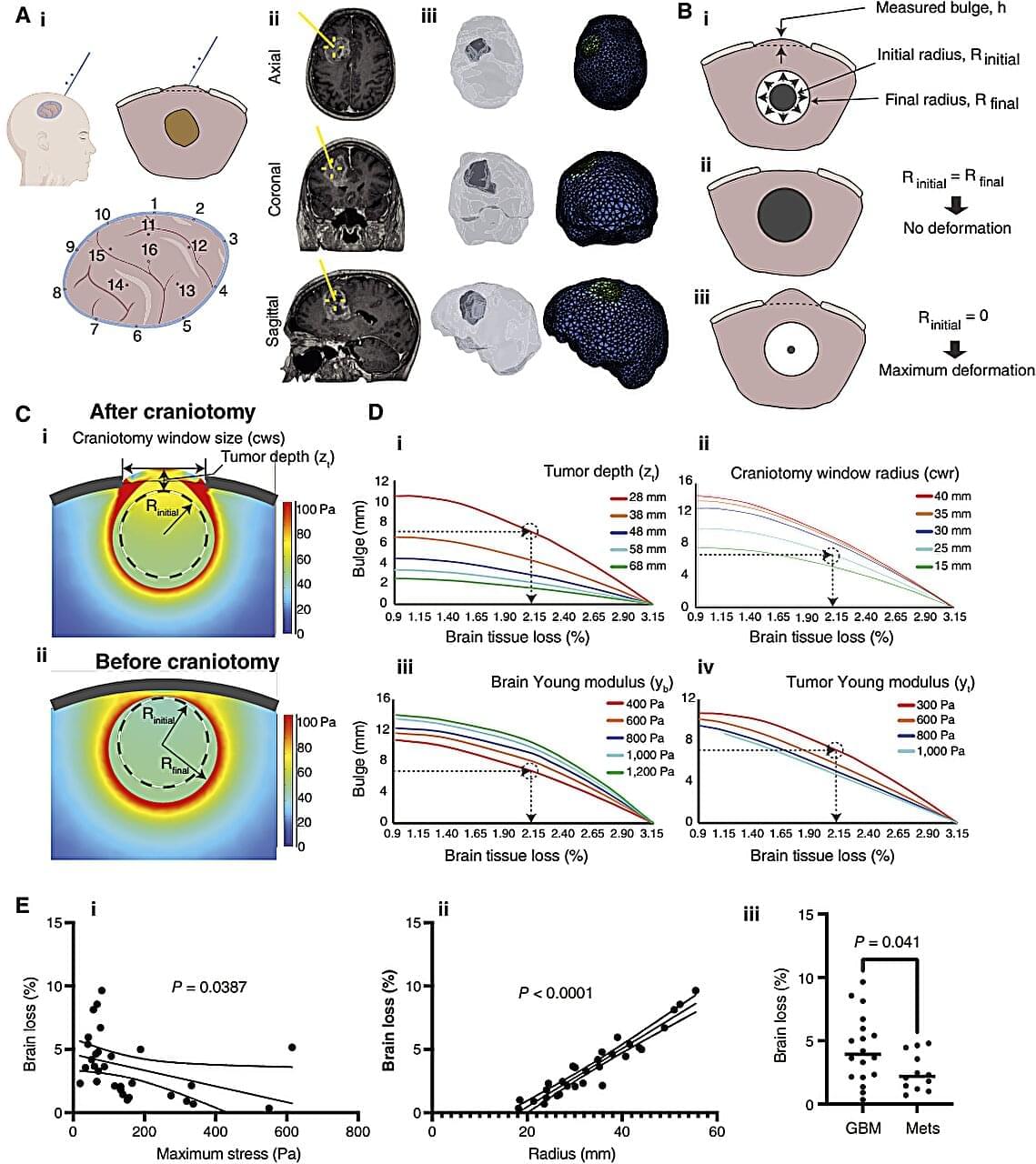

As brain tumors grow, they must do one of two things: push against the brain or use finger-like extensions to invade and destroy surrounding tissue.

Previous research found that tumors that push—or put mechanical force on the brain—cause more neurological dysfunction than tumors that destroy tissue. But what else can these different tactics of tumor growth tell us?

Now, the same team of researchers from the University of Notre Dame, Harvard Medical School/Massachusetts General Hospital, and Boston University has developed a technique for measuring a brain tumor’s mechanical force and a new model to estimate how much brain tissue a patient has lost. Published in Clinical Cancer Research, the study explains how these measurements may help inform patient care and be adopted into surgeons’ daily workflow.

Stores of glucose in the brain could play a much more significant role in the pathological degeneration of neurons than scientists realized, opening the way to new treatments for conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s is a tauopathy; a condition characterized by harmful build-ups of tau proteins inside neurons. It’s not clear, however, if these build-ups are a cause or a consequence of the disease. A new study now adds important detail by revealing significant interactions between tau and glucose in its stored form of glycogen.

Led by a team from the Buck Institute for Research on Aging in the US, the research sheds new light on the functions of glycogen in the brain. Before now, it’s only been regarded as an energy backup for the liver and the muscles.