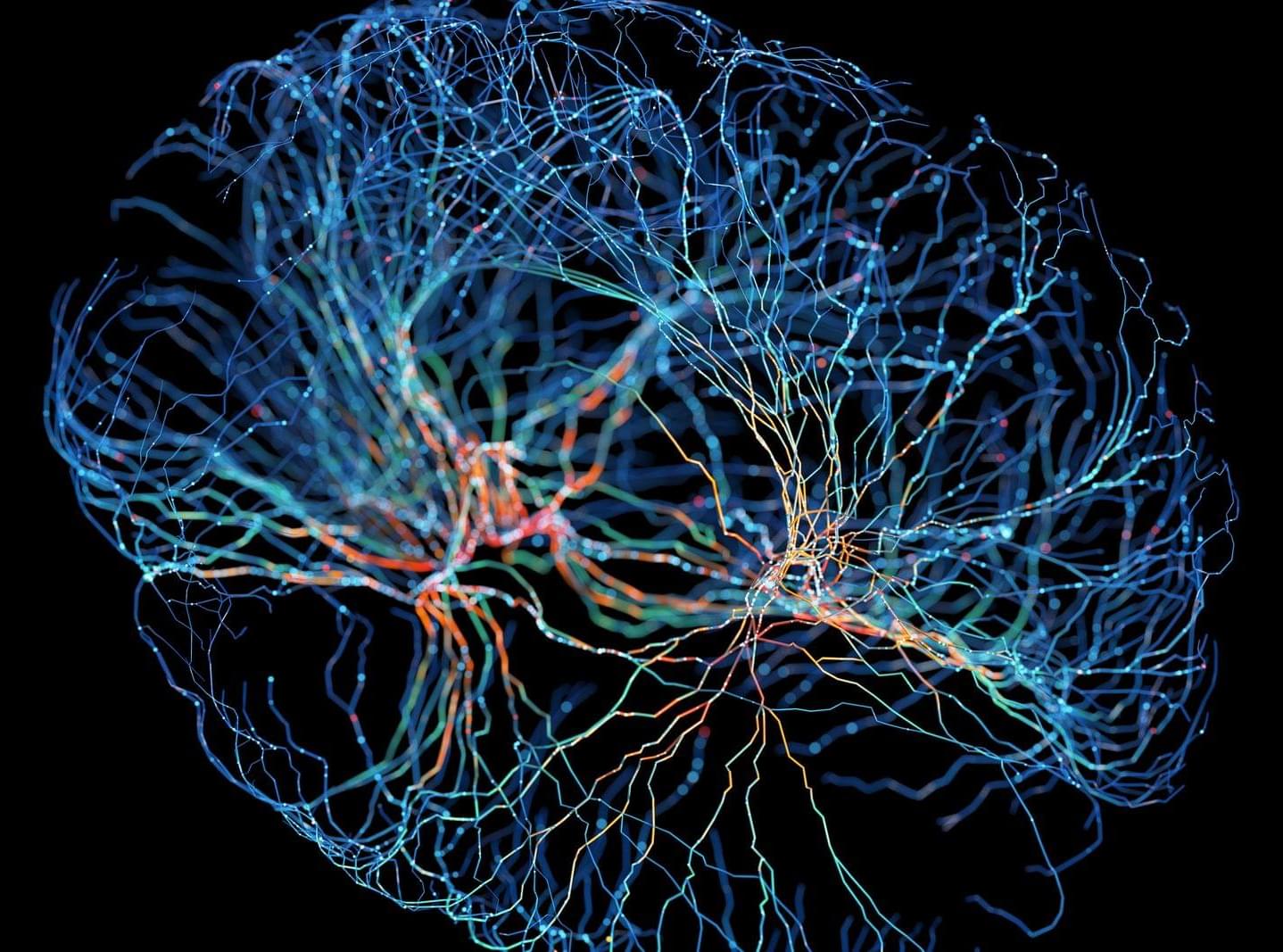

Scientists have identified a previously unknown group of inhibitory neurons defined by the adhesion molecule Kirrel3.

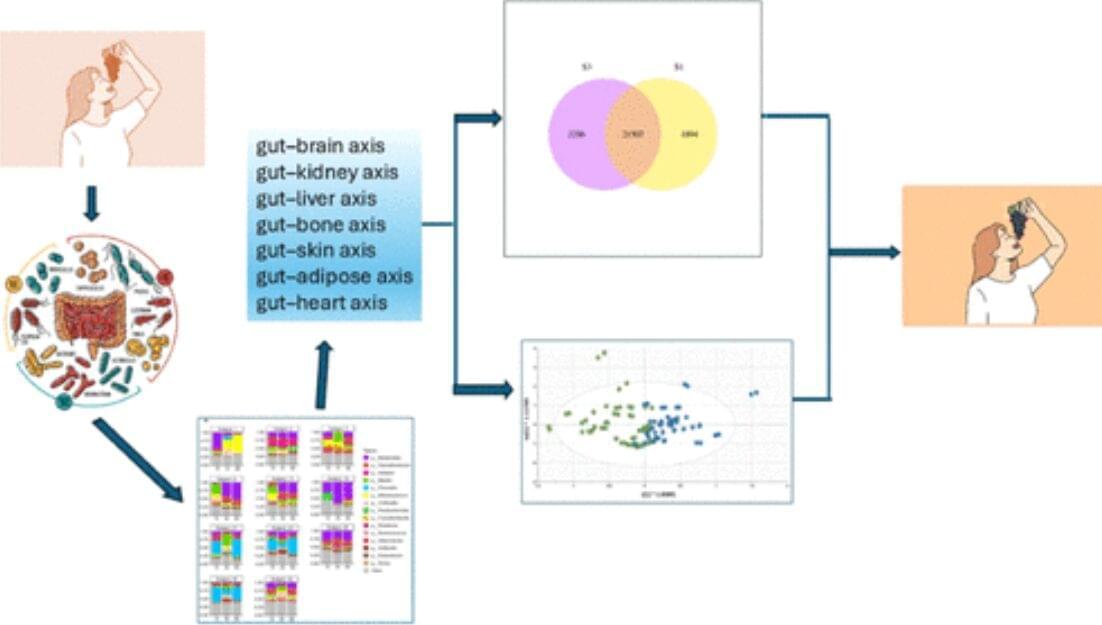

Fresh grapes contain a potent mix of over 1,600 compounds that benefit heart, brain, skin, and gut health. New evidence suggests they deserve official superfood recognition, with benefits even at the genetic level.

A new article appearing in the current issue of the peer-reviewed Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry explores the concept of “superfoods” and makes a case that fresh grapes have earned what should be a prominent position in the superfood family. The author, leading resveratrol and cancer researcher John M. Pezzuto, Ph.D., D.Sc., Dean of the College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences at Western New England University, brings forth an array of evidence to support his perspective on this issue.

As noted in the article, the term “superfood” is a common word without an official definition or established criteria. Mainstream superfoods are typically part of the Mediterranean Diet and generally rich in natural plant compounds that are beneficial to a person’s health. Pezzuto addresses the broader topic of superfoods in detail, then makes the scientific case for grapes, noting that fresh grapes are underplayed in this arena and often not included with mention of other similar foods, such as berries.

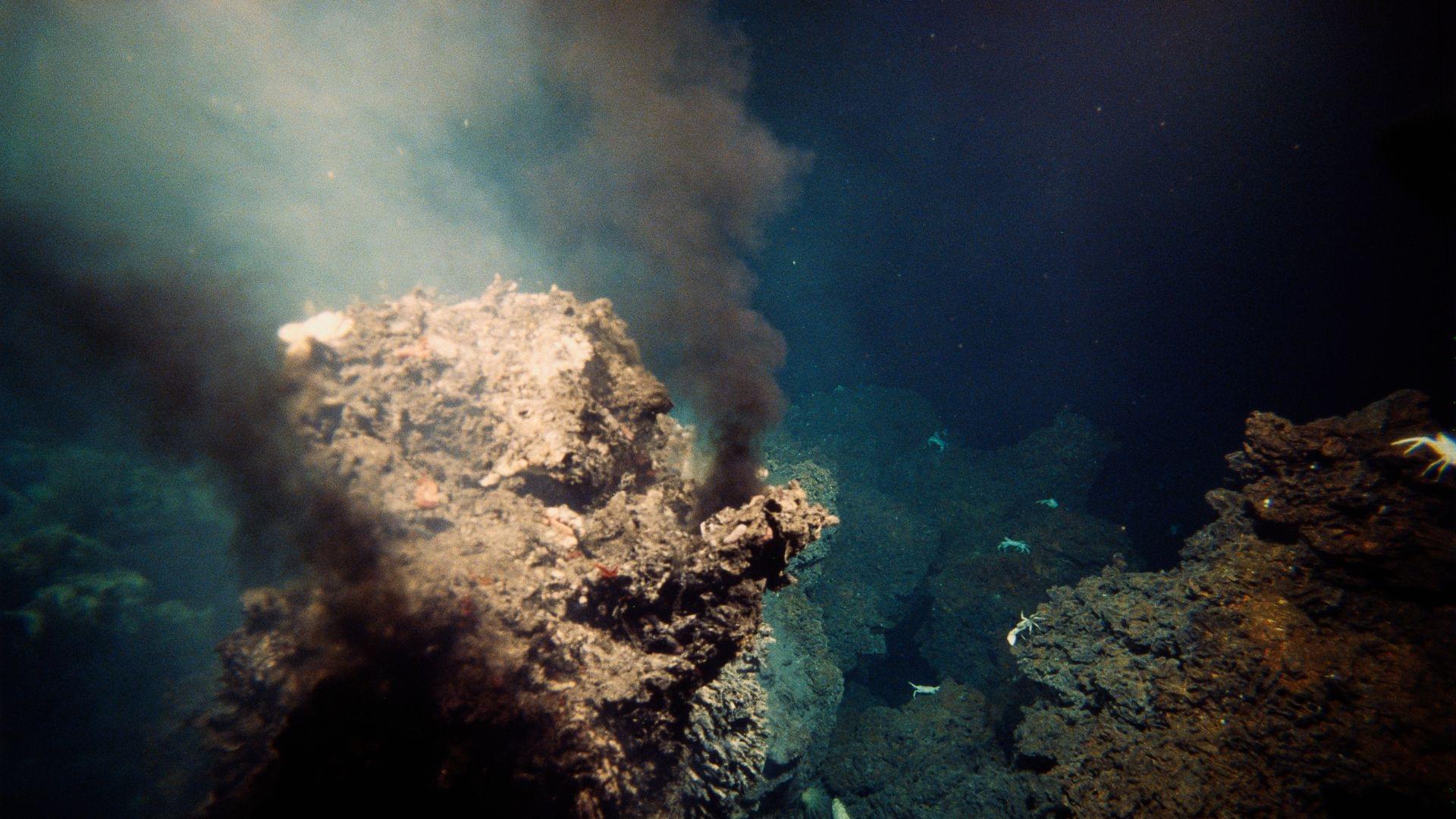

100x larger hydrogen-rich hydrothermal system beneath western Pacific seafloor discovered.

Researchers revealed that the Kunlun hydrothermal field—a tectonically active site roughly 80 kilometers west of the Mussau Trench on the Caroline Plate—comprises 20 large seafloor depressions (some exceeding one kilometer in diameter) clustered together like a pipe swarm, a group of vertical or steeply inclined cylindrical rock structures that funnel liquid or gas from Earth’s interior.

The total area is 11.1 square kilometers, i.e., over a hundred times larger than the Lost City, a unique deep-sea hydrothermal field located on the Atlantis Massif, a section of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

“The Kunlun system stands out for its exceptionally high hydrogen flux, scale, and unique geological setting,” said Prof. SUN Weidong, the study’s corresponding author. “It shows that serpentinization-driven hydrogen generation can occur far from mid-ocean ridges, challenging long-held assumptions.”

For centuries, philosophers and scientists have speculated about the mysterious connections between human minds. Now, new research in neuroscience suggests that our brains may be linked in a very real, physical way — through extremely low frequency (ELF) electromagnetic waves.

Neuroscientists studying brain activity have found that the human brain not only generates its own electrical signals but also emits faint electromagnetic waves at extremely low frequencies. These ELF waves, which typically range from 1 to 30 Hertz, are so subtle that they were once thought to be biologically insignificant. However, recent experiments show that these signals can extend beyond the skull and interact with the electromagnetic environment around us.

What’s even more remarkable is that similar ELF patterns appear across different individuals, raising the possibility that brains can “tune in” to each other through this shared frequency spectrum.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Tonix Pharmaceuticals’ Tonmya (cyclobenzaprine HCl, formerly known as TNX-102 SL), a novel treatment form for fibromyalgia.1 The drug is now the first in a new category of non-opioid analgesics for fibromyalgia and the first new medication for this disorder in 15 years.

The FDA’s approval cited efficacy from 2 double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 clinical trials of almost 1,000 patients that evaluated Tonmya as treatment for fibromyalgia. Across both phase 3 trials, Tonmya significantly reduced daily pain scores compared with placebo at the primary endpoint of 14 weeks. In these trials, a greater percentage of patients taking Tonmya experienced a clinically meaningful (≥30%) improvement in their pain after 3 months, as compared with placebo. Across phase 3 clinical trials with over 1,400 patients evaluated, Tonmya was generally well tolerated. The most common adverse events (incidence ≥2%) included oral hypoesthesia, oral discomfort, abnormal product taste, somnolence, oral paresthesia, oral pain, fatigue, dry mouth, and aphthous ulcer.

Psychiatric Times is the connection to Psychiatry and Mental Health, featuring clinical updates, expert views, and research news in multimedia formats.

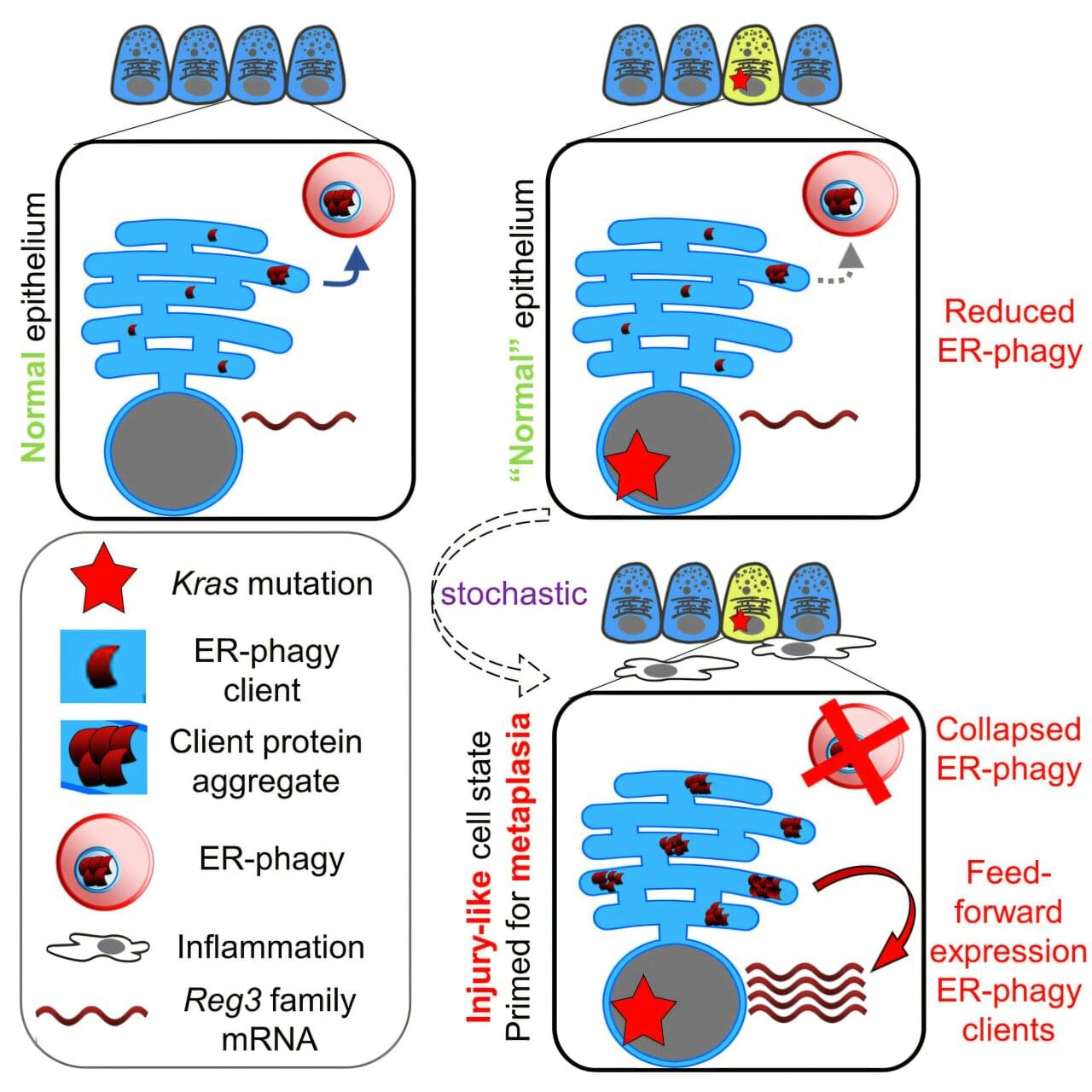

Scientists have uncovered dementia-like behavior in pancreas cells at risk of turning into cancer. The findings provide clues that could help in the treatment and prevention of pancreatic cancer, a difficult-to-treat disease linked to 6,900 deaths in the UK every year.

The research was published in the journal Developmental Cell in a paper titled “ER-phagy and proteostasis defects prime pancreatic epithelial state changes in KRAS-mediated oncogenesis.”

Researchers from the Cancer Research UK Scotland Center studied pancreas cells in mice over time, to see what was causing healthy cells to turn into cancer cells. They discovered that pancreatic cells at risk of becoming cancerous, known as pre-cancers, develop faults in the cell’s recycling process (known as “autophagy”).

Researchers from ShanghaiTech University, including Zhen-Ge Luo, used brain organoids derived from individuals with fAD to examine disease-related changes that occur during early brain development. The organoids, which are lab-grown models of human brain tissue, displayed several features associated with AD: elevated amyloid protein accumulation, a reduction in mature neurons, increased cell death and gene expression differences relative to healthy controls.

Role of thymosin β4 in brain pathology

Among the differentially expressed genes, the researchers identified TMSB4X, which encodes thymosin β4 (Tβ4), a protein with anti-inflammatory properties. TMSB4X expression was reduced in both the fAD organoids and in neurons from post-mortem samples of individuals with AD, suggesting a possible link between lower Tβ4 levels and disease pathology.

Ultimately, HAR123 promotes a particularly advanced human trait called cognitive flexibility, or the ability to unlearn and replace previous knowledge.

In addition to providing new insights into the biology of the human brain, the results also offer a molecular explanation for some of the radical changes that have occurred in the human brain over the course of our evolution. This is supported, for example, by the authors’ finding that the human version of HAR123 exerts different molecular and cellular effects than the chimpanzee version in both stem cells and neuron precursor cells in a petri dish.

Further research is needed to more fully understand the molecular action of HAR123 and whether the human version of HAR123 does indeed confer human-specific neural traits. This line of research could lead us to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying many neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism.

To protect users’ privacy, they chose a passphrase to activate the device that was unlikely to come up in everyday speech: “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang,” the title of the 1964 Ian Fleming novel and 1968 movie. The technology would start translating thoughts when it detected the phrase, which, for one participant, it did with 98.75 percent accuracy.

In the tests, the researchers asked the participants—all four of whom have some trouble speaking—to either attempt saying a set of seven words or to merely think them. They found the patterns of neural activity and regions of the brain used in both scenarios were similar, but the inner thoughts produced weaker signals.

Then, the team trained the computer system on the signals produced when participants thought words from a 125,000-word vocabulary. When the users then thought sentences with these words, the device translated the resulting brain activity. The technology produced words with an error rate of 26 to 54 percent, making it the most accurate attempt to decode inner speech to date, Science reports.