Neuroinflammation, a prolonged activation of the brain’s immune system prompted by infections or other factors, has been linked to the disruption of normal mental functions. Past studies, for instance, have found that neuroinflammation plays a central role in neurodegenerative diseases, medical conditions characterized by the progressive degradation of cells in the spinal cord and brain.

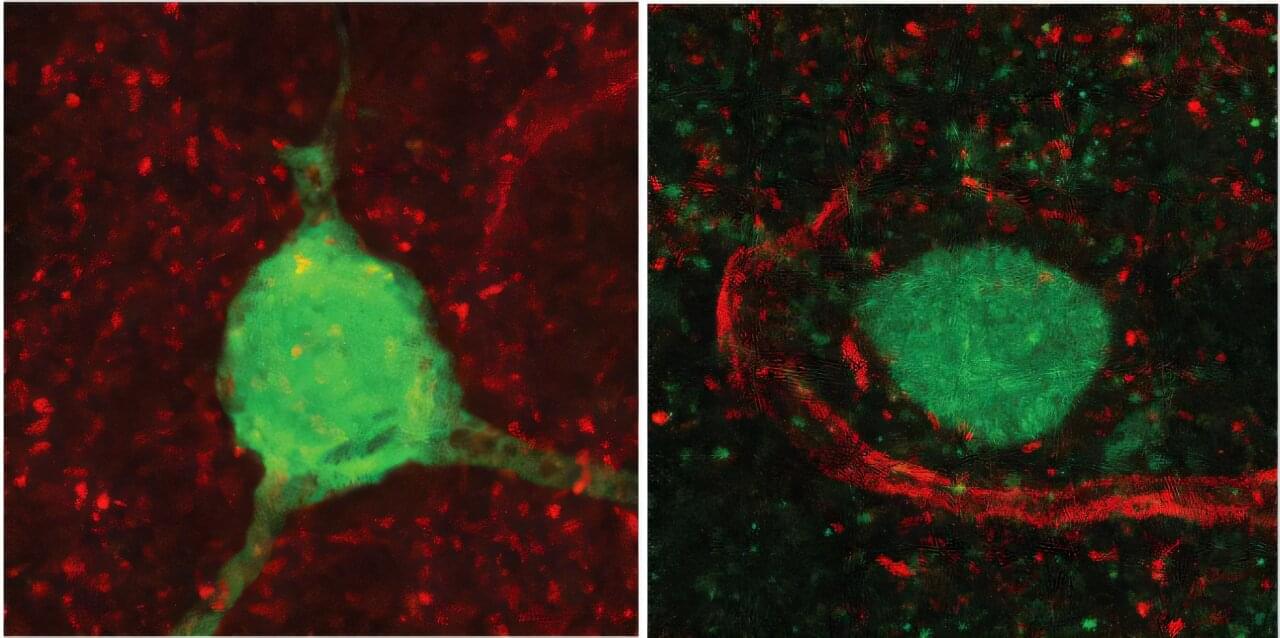

When inflammation is taking place, cells release proteins that act as signals between immune cells, also known as cytokines. While some studies have linked a specific cytokine called interleukin-1 (IL-1) to changes in brain function, the mechanisms through which it could contribute to a decline in mental capabilities remain poorly understood.

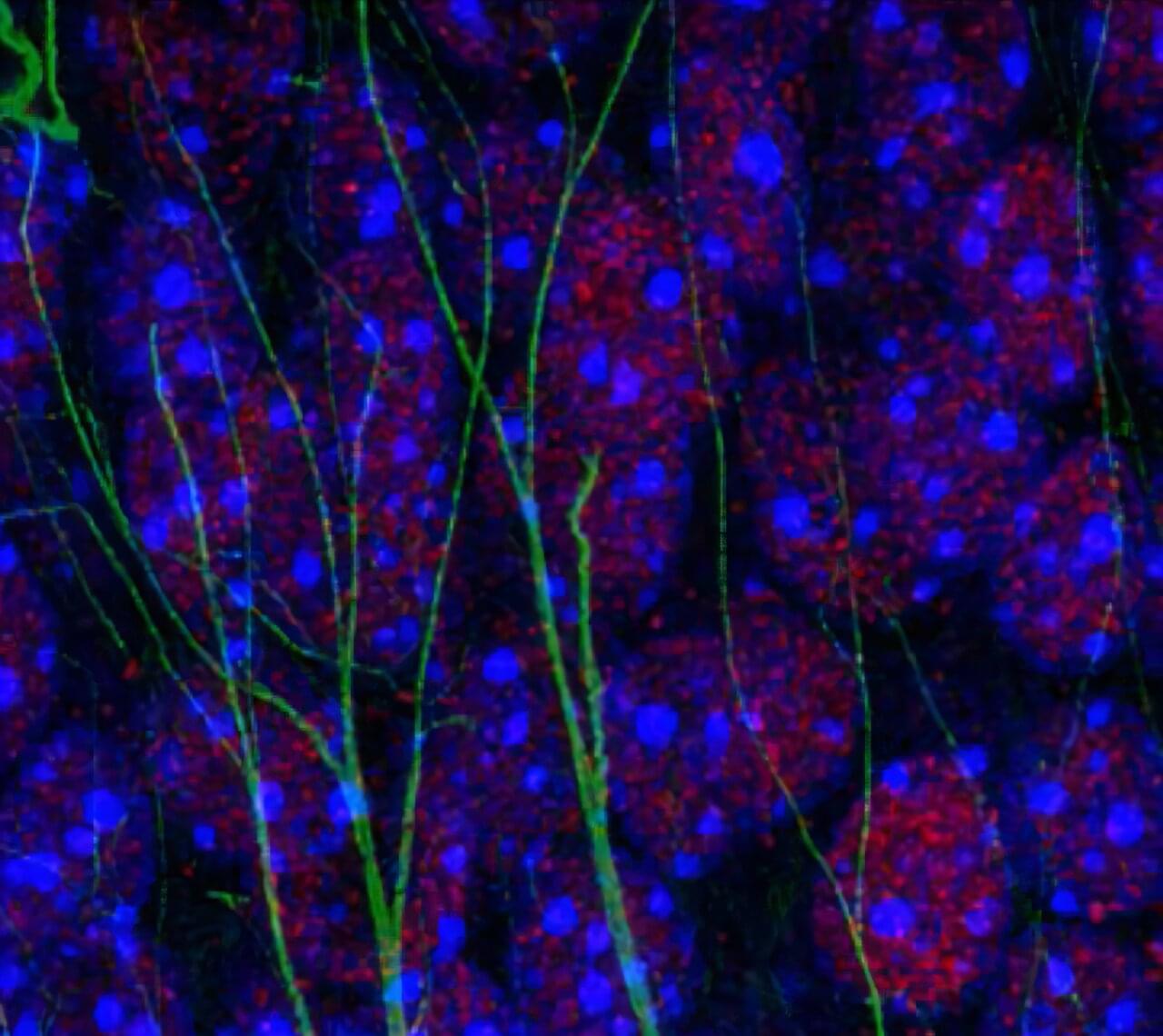

Researchers at the University of Toulouse INSERM and CNRS recently carried out a study involving mice aimed at better understanding these mechanisms. Their paper, published in Nature Neuroscience, particularly focused on neuroinflammation elicited by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii), which is responsible for a well-known illness called toxoplasmosis.