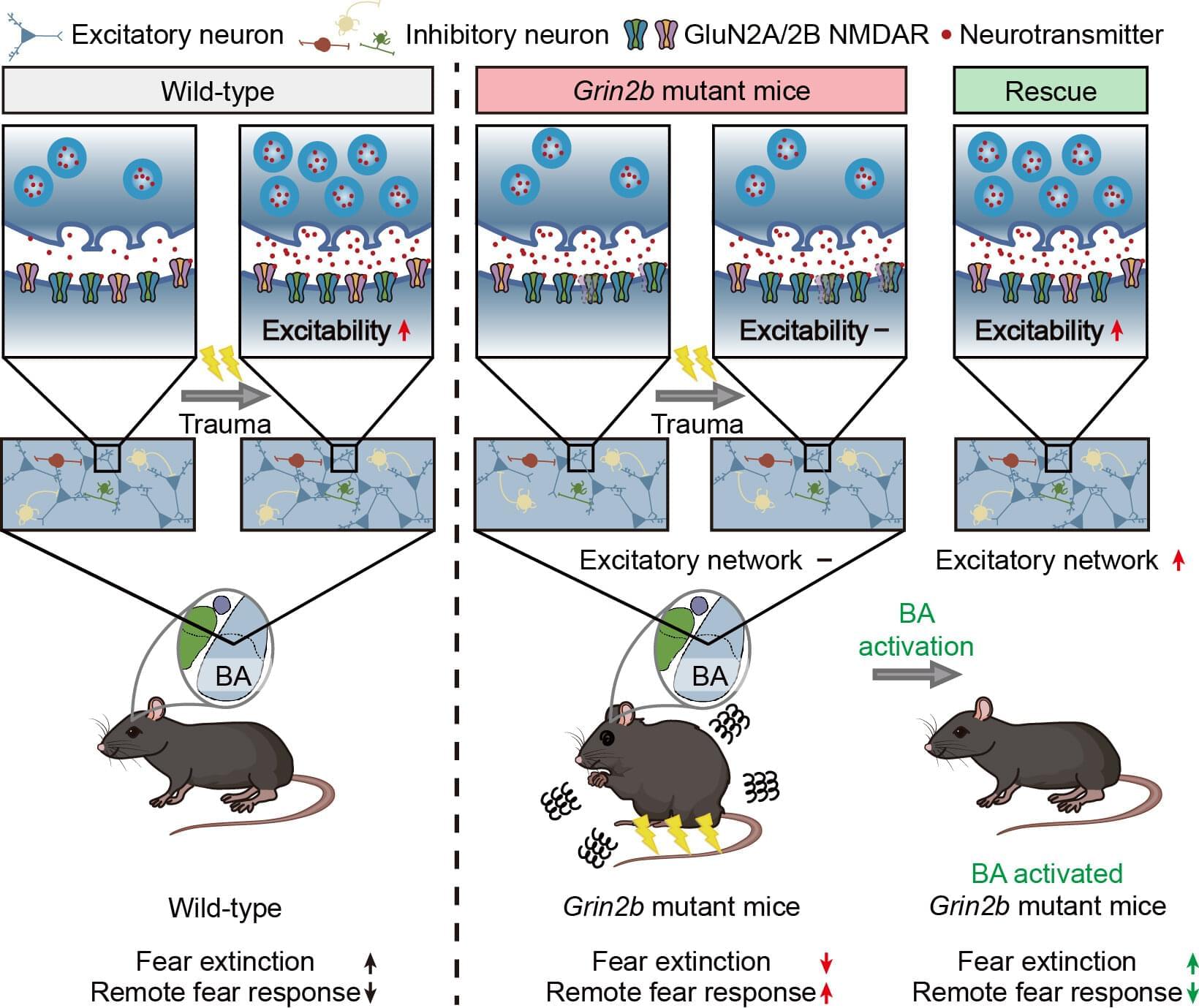

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is widely known for its core features, which include difficulties in social communication and repetitive behaviors. But beyond these, many individuals with ASD also struggle with comorbid conditions, particularly anxiety.

Nearly 40% of children with ASD experience anxiety disorders and often show unusually heightened fear responses. Studies have even suggested that people with ASD may be more vulnerable to trauma, unable to “erase” fear memories, which resembles symptoms seen in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Until now, most evidence for PTSD-like symptoms in ASD has relied on self-reports, leaving the underlying brain mechanisms unclear.