Observational studies of psychiatric diseases such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression have long tied viral infections with behavioral symptoms in these disorders, but scientists have been unable to find direct evidence of suspected viruses in the brain. Experts say that’s possibly because viruses may not get directly inside the brain, but may target the brain lining instead.

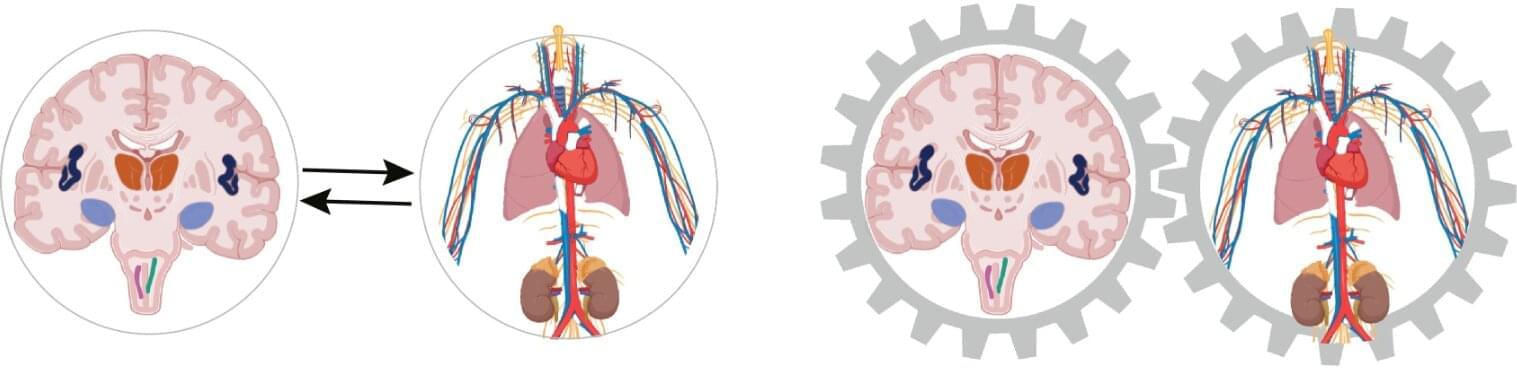

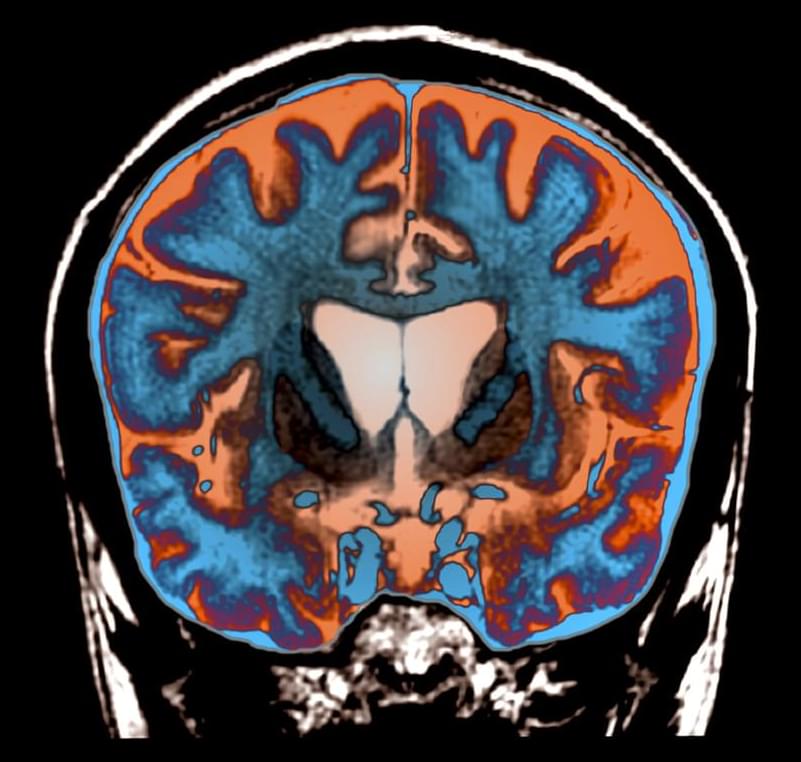

After testing that idea using postmortem human brain samples and the electronic medical records of 285 million patients, a team of Johns Hopkins Medicine scientists says it has found such evidence in the form of the liver-damaging hepatitis C virus in the human brain’s choroid plexus, a collection of cells that make up the lining of the fluid-filled cavities, or ventricles, and — notably — produce the cerebrospinal fluid that protects the brain and spinal cord…

…’Our findings show that it’s possible that some people may be having psychiatric symptoms because they have an infection, and since the hepatitis C infection is treatable, it might be possible for this patient subset to be treated with antiviral drugs and not have to deal with psychiatric symptoms,’ Sabunciyan says.