Yale and Oxford researchers say exercise is more important to your mental health than your economic status.

University of Maryland researchers showed sight deprivation changes how groups of neurons work together and alters their sensitivity to different frequencies.

Scientists have known that depriving adult mice of vision can increase the sensitivity of individual neurons in the part of the brain devoted to hearing. New research from biologists at the University of Maryland revealed that sight deprivation also changes the way brain cells interact with one another, altering neuronal networks and shifting the mice’s sensitivity to different frequencies. The research was published in the November 19, 2019 issue of the journal eNeuro.

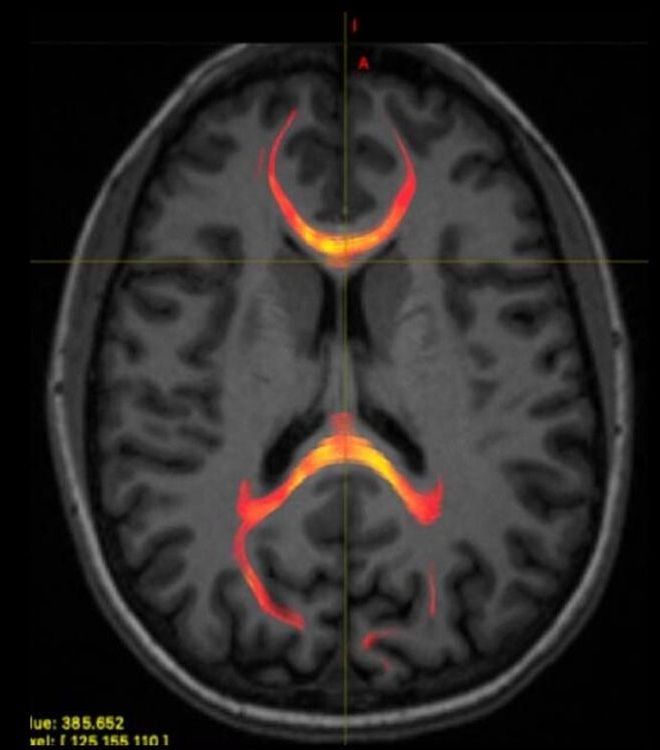

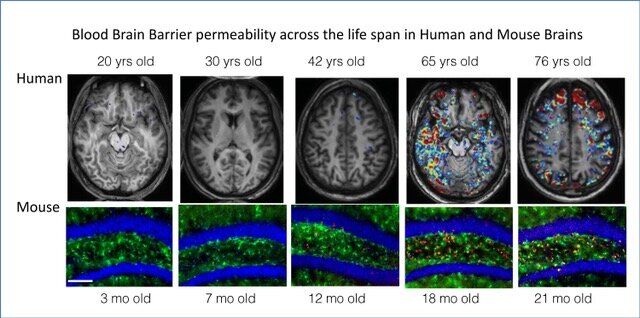

Drugs that tamp down inflammation in the brain could slow or even reverse the cognitive decline that comes with age.

In a publication appearing today in the journal Science Translational Medicine, University of California, Berkeley, and Ben-Gurion University scientists report that senile mice given one such drug had fewer signs of brain inflammation and were better able to learn new tasks, becoming almost as adept as mice half their age.

“We tend to think about the aged brain in the same way we think about neurodegeneration: Age involves loss of function and dead cells. But our new data tell a different story about why the aged brain is not functioning well: It is because of this “fog” of inflammatory load,” said Daniela Kaufer, a UC Berkeley professor of integrative biology and a senior author, along with Alon Friedman of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel and Dalhousie University in Canada. “But when you remove that inflammatory fog, within days the aged brain acts like a young brain. It is a really, really optimistic finding, in terms of the capacity for plasticity that exists in the brain. We can reverse brain aging.”

Scientists say creation could be used to circumvent nerve damage and help paralysed people regain movement.

Ian Sample Science editor.

Some people hope to cheat death by storing their consciousness digitally. Science isn’t quite there yet, but we’ve done enough brain and memory research to have immediate implications – and to start asking uncomfortable questions.

The idea of attaining de facto immortality by translating your brain into code and storing your personality as a digital copy online has been captivating people’s imagination for quite some time. It is particularly popular among transhumanists, people who advocate enhancing human intellect and physiology through the most sophisticated technology available.

As the most technologically advanced nations around the world pour resources into brain studies and yesterday’s science fiction becomes reality, it might seem that humanity is nearing a breakthrough in this field. Could the ability to become a “ghost in the shell” – like in the iconic cyberpunk Japanese manga, or the 2017 film – be just around the corner?

Without hardly noticing, we make countless decisions: to turn left or right on the bus? To wait or to accelerate? To look or to ignore? In the run-up to these decisions the brain evaluates sensory information and only then does it generate a behavior. For the first time, scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology were able to follow such a decision-making process throughout an entire vertebrate brain. Their new approach shows how and where the zebrafish brain transforms the movement of the environment into a decision that causes the fish to swim in a specific direction.

Young zebrafish are tiny. Their brain is not much bigger than that of a fly and almost transparent. “We can therefore look into the entire brain and see what happens, for example, when a decision is made,” explains Elena Dragomir, who has done exactly this. “The first step was to find a behavioral paradigm that we could use to study decision making,” says Elena Dragomir. Other animal species, for example, are shown dots that move more or less in one direction. The animals can be trained to indicate their decision on the direction of the dots’ movement, and if it is correct, they receive a reward. The neurobiologists from Ruben Portugues’ group have now adapted this experimental setup for zebrafish. “The trick is that we use a reliable behavior called the optomotor response as a readout of the fish’s decision”.

If a fish drifts in a current, an image of the environment moves past its eyes. Fish will swim in the direction of the perceived optic flow to prevent drifting. Moving dots can trigger this optomotor response in the lab, and fish will turn either to the left or to right, depending on the direction of the moving dots. “We can also vary the difficulty of the decision, by changing the strength of the visual stimulus,” explains Ruben Portugues. “If a higher percentage of dots move in one direction, the fish will turn faster and more reliably to the correct direction.”

O.o.

Andy Pero, a survivor of the mind control tactics used in the Montauk Project experimentsinsights and repressed memories about his experience at secret military bases. Andy Pero underwent a program which used traumatic mind control and psychic power tactics similar to those used in the Montauk Project.

In an interview (read the full interview below) with Eve Frances Lorgen, Andy Pero shared his experience with trauma-based control of the mind and the Montauk explorations in consciousness. He recalled sessions where he was tortured and put through shock treatments. This is done to have the ability to reprogram participants to do things they were not able to previous to the programming.

According to so called conspiracy theories Mind control facilities are located all over the country. There is one in Rochester, New York, one in Paramus, New Jersey, Atlanta Georgia, at Dobbins Air Force Base, and one in Montauk, Long Island at Dobbins at Camp Hero.