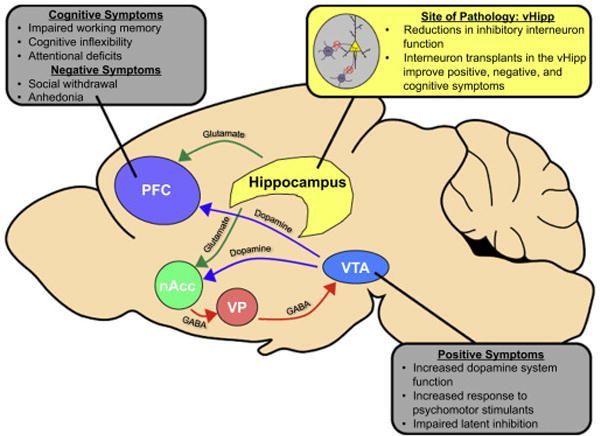

Schizophrenia is a devastating psychiatric disorder characterized by positive, negative and cognitive symptoms. While aberrant dopamine system function is typically associated with the positive symptoms of the disease, it is thought that this is secondary to pathology in afferent regions. Indeed, schizophrenia patients show dysregulated activity in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, two regions known to regulate dopamine neuron activity. These deficits in hippocampal and prefrontal cortical function are thought to result, in part, from reductions in inhibitory interneuron function in these brain regions. Therefore, it has been hypothesized that restoring interneuron function in the hippocampus and/or prefrontal cortex may be an effective treatment strategy for schizophrenia. In this article, we will discuss the evidence for interneuron pathology in schizophrenia and review recent advances in our understanding of interneuron development. Finally, we will explore how these advances have allowed us to test the therapeutic value of interneuron transplants in multiple preclinical models of schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia is devastating psychiatric disorder that affects approximately 1% of the population1. Positive symptoms, such as paranoia, grandiosity, delusions, and hallucinations, are often the most striking features of the disorder; however, schizophrenia patients also display characteristic negative and cognitive symptoms, which can be severely debilitating. Negative symptoms, such as blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, and social avoidance and cognitive symptoms, including disruptions in working memory, attentional deficits, disorganized thought, and cognitive inflexibility, can negatively influence social and occupational functioning and diminish quality of life2–4. Currently prescribed antipsychotic medications, which act as antagonists at the dopamine D2 receptor5, have been somewhat effective in treating the positive symptoms of schizophrenia6.