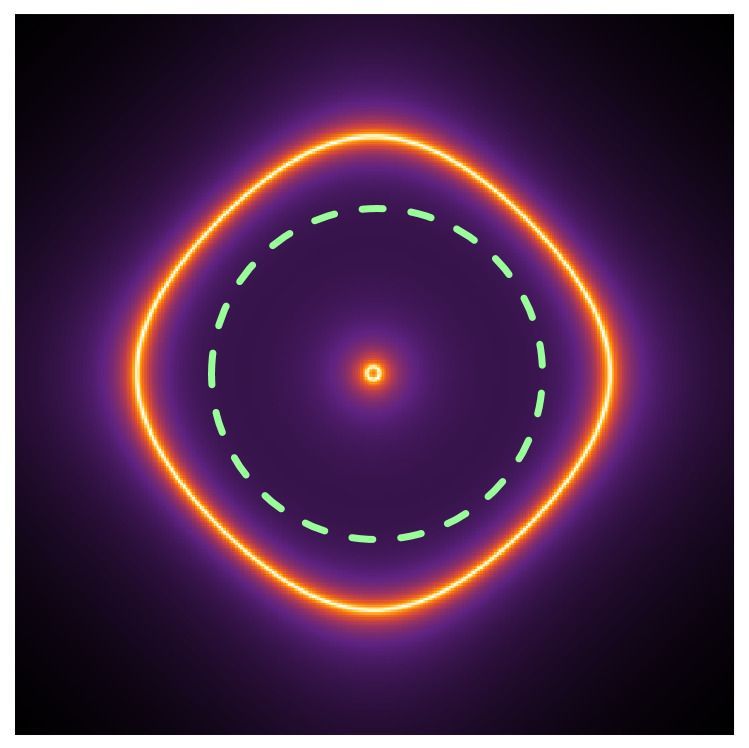

Majorana modes are, however, notoriously elusive. In part, this is because it is hard to create the conditions required to generate them in an experimental setting. Many theoretical proposals have predicted MZMs should be present in quasi-2D materials, which consist of a small number of 2D layers stacked on top of each other. However, all previous proposals required heterostructures – that is, structures where the stacked layers have differing material composition and structure. Practically, these heterostructures are difficult if not downright impossible to grow.

To make matters worse, Majorana modes can only be observed indirectly. Like detectives trying to catch a culprit with only circumstantial evidence, physicists have a hard time ruling out alternative explanations for the phenomena they observe. This has led to high-profile premature claims of Majorana discovery, including Microsoft Quantum Lab’s recent retraction of a Nature paper in which they purported to observe MZMs in nanowires.

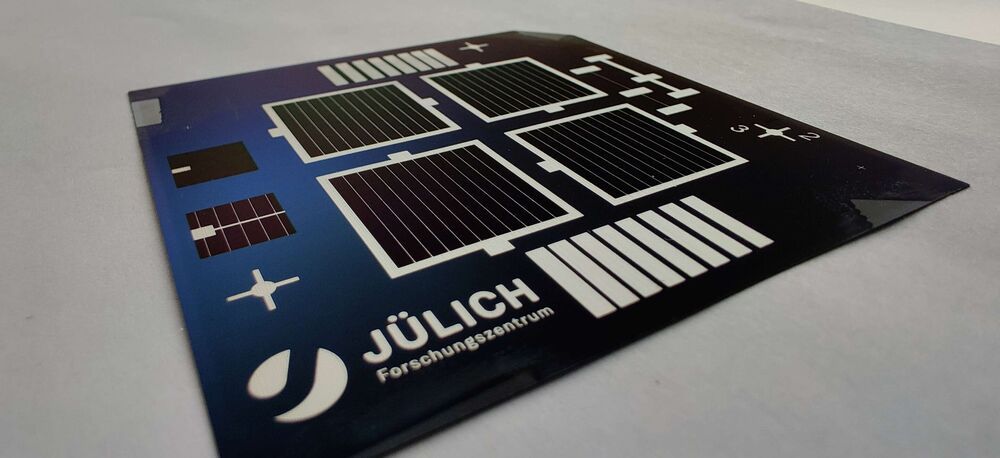

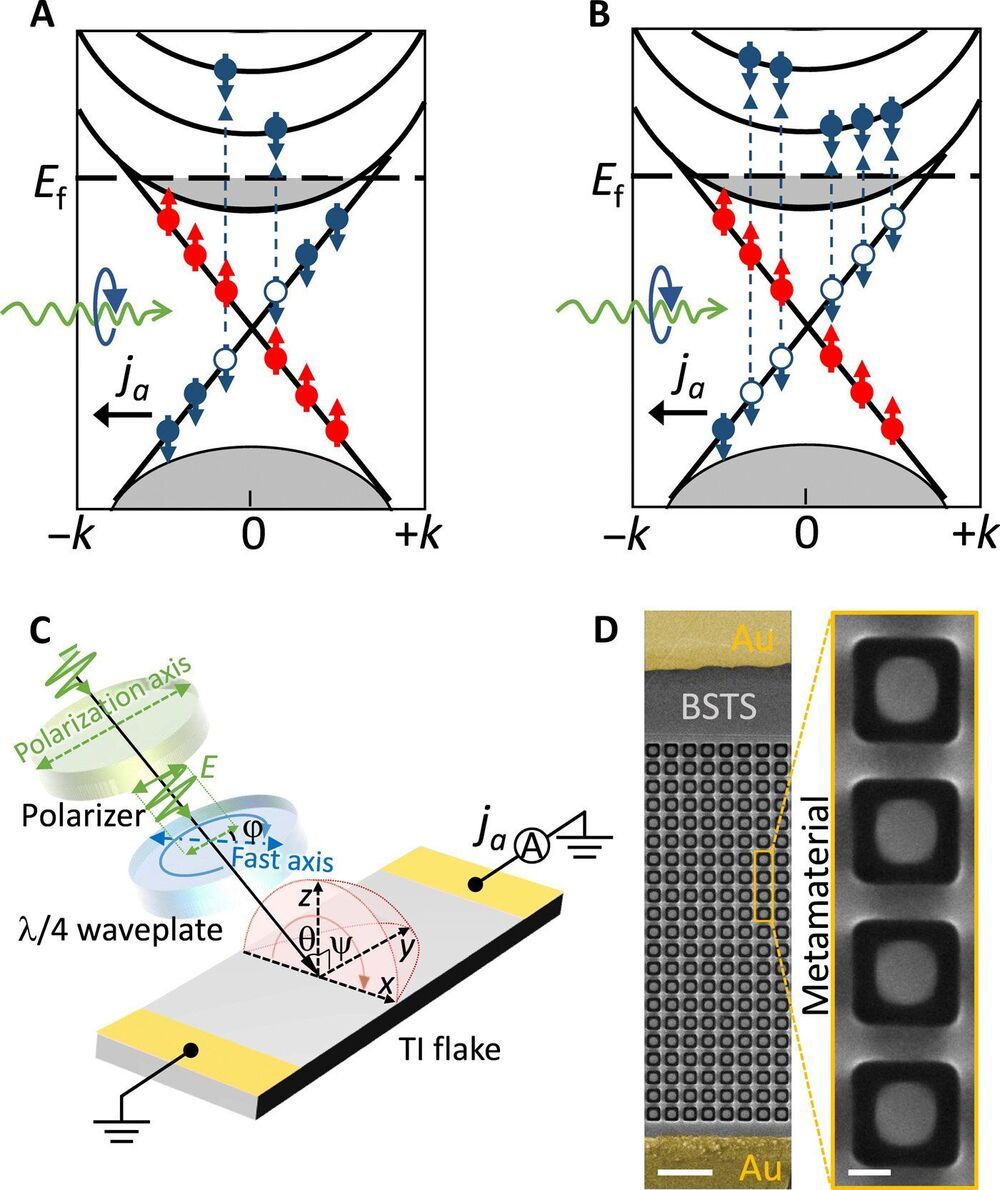

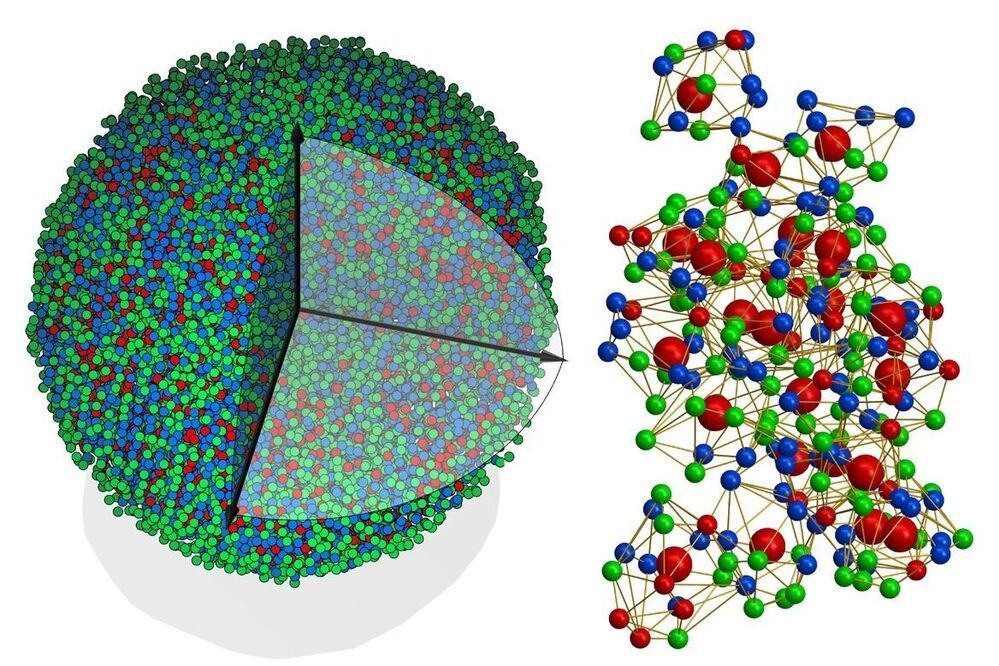

In their new work, Zhang and his coauthor show that Majorana modes should be present in a much simpler setting: thin films of an iron-based superconducting material. Like previous proposals, the system they study is quasi-2D, but crucially all layers are of the same kind. The iron-based thin films naturally accommodate Majorana fermions that are helical – left or right-handed – and move along the edges of the system in their preferred direction. This is due to a special “time-reversal” symmetry, wherein interchanging the left-moving and right-moving quasiparticles makes it look like time is propagating backwards in the system.