What we call laws of physics are often just mathematical descriptions of some part of nature. Ultimate physical laws probably don’t exist and physics is all the better for it, says theoretical physicist Sankar Das Sarma.

Avi Shporer, Research Scientist, with the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research via Chris Adami, Paul Davies, AIP Advances, EurekaAlert and University of Portsmouth

“Information,” wrote Arizona State University astrophysicist Paul Davies in an email to The Daily Galaxy, “is a concept that is both abstract and mathematical. It lies at the foundation of both biology and physics.”

Viewing information at the cosmic level, physicist Melvin Vopson at the University of Portsmouth in the UK has estimated in a paper how much information a single elementary particle, like an electron, stores about itself. He then used this calculation to estimate the staggering amount of information contained in the entire observable Universe. Practical experiments can now be used, he suggested, to test and refine these predictions, including research to prove or disprove the hypothesis that information is the fifth state of matter in the universe beyond solid, liquid, gas, and plasma.

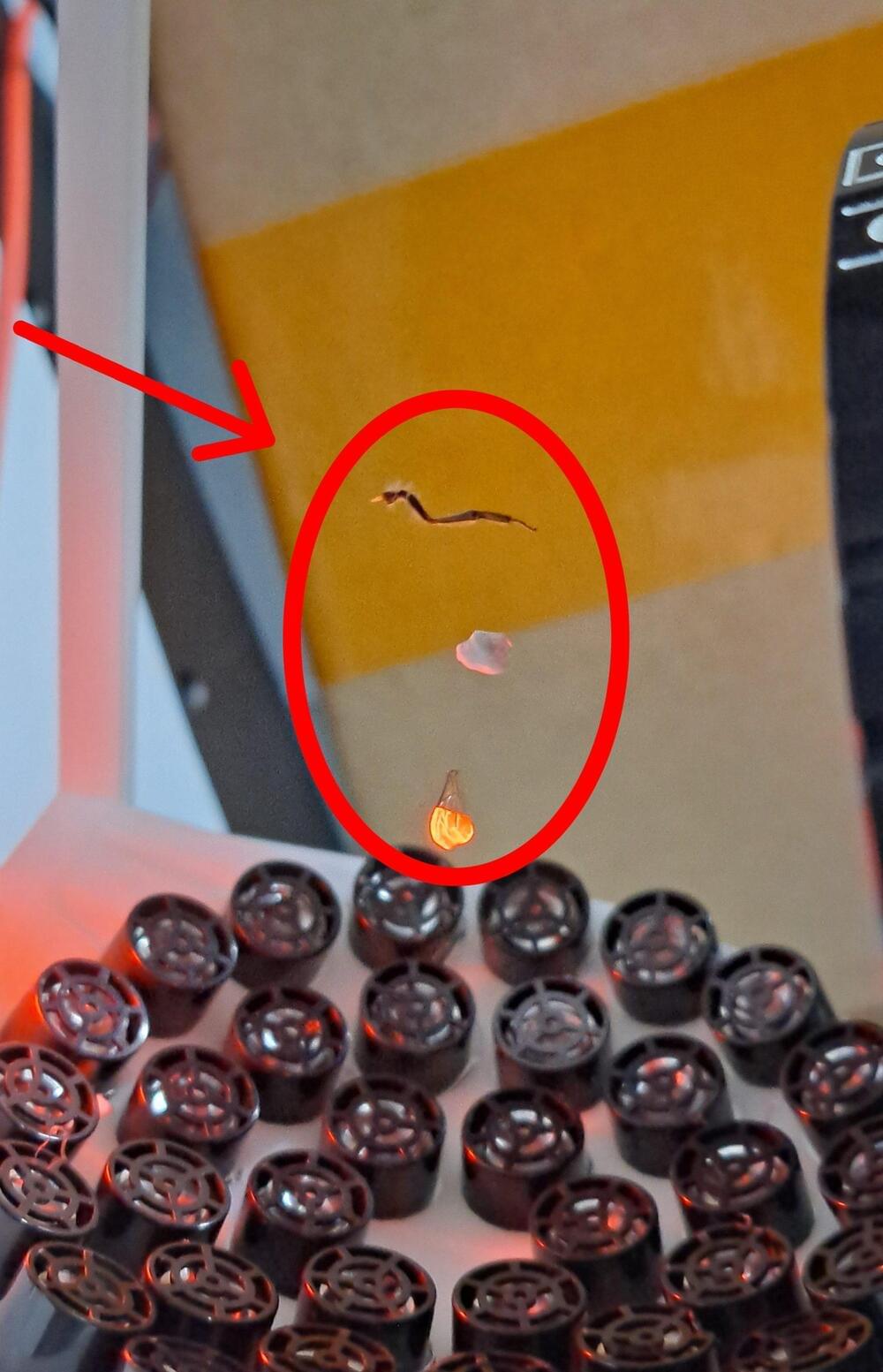

Scientists with the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and the University of New South Wales (UNSW) have developed a method that helps to fine-tune the control of particles using ultrasonic waves according to new research, which they say expands our understanding of the field of acoustic levitation.

The levitation of objects, once a phenomenon seen only in science fiction and fantasy, now represents a field in acoustics with practical applications in multiple research areas, industries, and even among hobbyists. However, the use of high-intensity sound waves to suspend small objects in the air is nothing new. The theoretical basis for overcoming gravity with the help of acoustic radiation pressure goes as far back as the 1930s, when researcher Louis King first studied the suspension of particles in the field of a sound wave, and how this demonstrates acoustic radiation force being exerted against them.

Later calculations beginning in the 1950s helped to further refine our understanding of the acoustic radiation force produced by the scattering of sound waves. However, the modern foundation for acoustic levitation science draws mainly from the work of superconductivity pioneer Lev. P. Gorkov, who was the first to synthesize previous studies and provide a solid mathematical basis for the phenomenon.

The concept of ‘anti-realism’ is widely seen as a fact of life for many physicists studying the mysterious effects of quantum mechanics. However, it also seems to contradict the assumptions of many other fields of research. In his research, Dr William Sulis at McMaster University in Canada explores the issue from a new perspective, by using a novel mathematical toolset named the ‘process algebra model’. In suggesting that reality itself is generated by interacting processes more fundamental than quantum particles, his theories could improve researchers’ understanding of fundamental processes in a wide variety of fields.

The concept of ‘locality’ states that objects and processes can only be influenced by other objects and processes in their immediate surroundings. It is a fundamental aspect of many fields of research and underpins all of the most complex systems we observe in nature, including living organisms. “Biologists and psychologists have known for centuries that the physical world is dominated by processes which are characterized by factors including transformation, interdependence, and information”, Dr Sulis explains. “Organisms are born, develop, continually exchange physical components and information with their environment, and eventually die.”

Beyond biology, the principle of locality also extends to Einstein’s theory of special relativity. Since the speed of light sets a fundamental speed limit on all processes in the universe, the theory states that no process can occur if it has not been triggered by another event in its past, at a close enough distance for light to travel between them within the time separating them. In general, these theories are unified by a concept which physicists call ‘realism’. Yet despite this seemingly intuitive rule, physicists have increasingly come to accept the idea that it doesn’t present a full description of how all processes unfold.

Our Wolfram Physics Project has provided a surprisingly successful picture of the underlying (deeply computational) structure of our physical universe. I’ll talk here about how our perception of that underlying structure is determined by what seem to be key features of our consciousness—and how this leads to detailed laws of physics as we experience them. Our Physics Project has led to the concept of the ruliad—the entangled limit of all possible computations—which seems to represent a common underlying structure from which both physics and mathematics emerge. I’ll talk about the comparison between physical and mathematical observers, and how their common features in consciousness lead to implications for general laws of “bulk mathematics”.

Stephen Wolfram is at his jovial peak in this technical interview regarding the Wolfram Physics project (theory of everything).

Sponsors: https://brilliant.org/TOE for 20% off. http://algo.com for supply chain AI.

Link to the Wolfram project: https://www.wolframphysics.org/

Patreon: https://patreon.com/curtjaimungal.

Crypto: https://tinyurl.com/cryptoTOE

PayPal: https://tinyurl.com/paypalTOE

Twitter: https://twitter.com/TOEwithCurt.

Discord Invite: https://discord.com/invite/kBcnfNVwqs.

iTunes: https://podcasts.apple.com/ca/podcast/better-left-unsaid-wit…1521758802

Pandora: https://pdora.co/33b9lfP

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/4gL14b92xAErofYQA7bU4e.

Subreddit r/TheoriesOfEverything: https://reddit.com/r/theoriesofeverything.

Merch: https://tinyurl.com/TOEmerch.

TIMESTAMPS:

00:00:00 Introduction.

00:02:26 Behind the scenes.

00:04:00 Wolfram critiques are from people who haven’t read the papers (generally)

00:10:39 The Wolfram Model (Theory of Everything) overview in under 20 minutes.

00:29:35 Causal graph vs. multiway graph.

00:39:42 Global confluence and causal invariance.

00:44:06 Rulial space.

00:49:05 How to build your own Theory of Everything.

00:54:00 Computational reducibility and irreducibility.

00:59:14 Speaking to aliens / communication with other life forms.

01:06:06 Extra-terrestrials could be all around us, and we’d never see it.

01:10:03 Is the universe conscious? What is “intelligence”?

01:13:03 Do photons experience time? (in the Wolfram model)

01:15:07 “Speed of light” in rulial space.

01:16:37 Principle of computational equivalence.

01:21:13 Irreducibility vs undecidability and computational equivalence.

01:23:47 Is infinity “real”?

01:28:08 Discrete vs continuous space.

01:33:40 Testing discrete space with the cosmic background radiation (CMB)

01:34:35 Multiple dimensions of time.

01:36:12 Defining “beauty” in mathematics, as geodesics in proof space.

01:37:29 Particles are “black holes” in branchial space.

01:39:44 New Feynman stories about his abjuring of woo woo.

01:43:52 Holographic principle / AdS CFT correspondence, and particles as black holes.

01:46:38 Wolfram’s view on cryptocurrencies, and how his company trades in crypto [Amjad Hussain]

01:57:38 Einstein field equations in economics.

02:03:04 How to revolutionize a field of study as a beginner.

02:04:50 Bonus section of Curt’s thoughts and questions.

Just wrapped (April 2021) a documentary called Better Left Unsaid http://betterleftunsaidfilm.com on the topic of “when does the left go too far?” Visit that site if you’d like to watch it.

Year 2012 😗

A Sierpinksi carpet is one of the more famous fractal objects in mathematics. Creating one is an iterative procedure. Start with a square, divide it into nine equal squares and remove the central one. That leaves eight squares around a central square hole. In the next iteration, repeat this process with each of the eight remaining squares and so on (see above). One interesting problem is to find the area of a Sierpinski triangle. Clearly this changes with each iteration. Assuming the original square has area equal to 1, the area after the first iteration is 8/9. After the second iteration, it is (8÷9)^2; after the third it is (8÷9)^3 and so on.

Kathryn Tunyasuvunakool grew up surrounded by scientific activities carried out at home by her mother—who went to university a few years after Tunyasuvunakool was born. One day a pendulum hung from a ceiling in her family’s home, Tunyasuvunakool’s mother standing next to it, timing the swings for a science assignment. Another day, fossil samples littered the dining table, her mother scrutinizing their patterns for a report. This early exposure to science imbued Tunyasuvunakool with the idea that science was fun and that having a career in science was an attainable goal. “From early on I was desperate to go to university and be a scientist,” she says.

Tunyasuvunakool fulfilled that ambition, studying math as an undergraduate, and computational biology as a graduate student. During her PhD work she helped create a model that captured various elements of the development of a soil-inhabiting roundworm called Caenorhabditis elegans, a popular organism for both biologists and physicists to study. She also developed a love for programming, which, she says, lent itself naturally to a jump into software engineering. Today Tunyasuvunakool is part of the team behind DeepMind’s AlphaFold—a protein-structure-prediction tool. Physics Magazine spoke to her to find out more about this software, which recently won two of its makers a Breakthrough Prize, and about why she’s excited for the potential discoveries it could enable.

All interviews are edited for brevity and clarity.

Never miss a talk! SUBSCRIBE to the TEDx channel: http://bit.ly/1FAg8hB

Mathematics and sex are deeply intertwined. From using mathematics to reveal patterns in our sex lives, to using sex to prime our brain for certain types of problems, to understanding them both in terms of the evolutionary roots of our brain, Dr Clio Cresswell shares her insight into it all.

Dr Clio Cresswell is a Senior Lecturer in Mathematics at The University of Sydney researching the evolution of mathematical thought and the role of mathematics in society. Born in England, she spent part of her childhood on a Greek island, and was then schooled in the south of France where she studied Visual Art. At eighteen she simultaneously discovered the joys of Australia and mathematics, following on to win the University Medal and complete a PhD in mathematics at The University of New South Wales. Communicating mathematics is her field and passion. Clio has appeared on panel shows commenting, debating and interviewing; authored book reviews and opinion pieces; joined breakfast radio teams and current affair programs; always there highlighting the mathematical element to our lives. She is author of Mathematics and Sex.

TEDxSydney is an independently organised event licensed from TED by longtime TEDster, Remo Giuffré (REMO General Store) and organised by his General Thinking network of fellow thinkers and other long time collaborators.

TEDxSydney has become the leading platform and pipeline for the propagation of Australian ideas, creativity, innovation and culture to the rest of the world.

In the spirit of ideas worth spreading, TEDx is a program of local, self-organized events that bring people together to share a TED-like experience. At a TEDx event, TEDTalks video and live speakers combine to spark deep discussion and connection in a small group. These local, self-organized events are branded TEDx, where x = independently organized TED event. The TED Conference provides general guidance for the TEDx program, but individual TEDx events are self-organized.* (*Subject to certain rules and regulations)

Sound waves, like an invisible pair of tweezers, can be used to levitate small objects in the air. Although DIY acoustic levitation kits are readily available online, the technology has important applications in both research and industry, including the manipulation of delicate materials like biological cells.

Researchers at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and the University of New South Wales (UNSW) have recently demonstrated that in order to precisely control a particle using ultrasonic waves, it is necessary to take into account both the shape of the particle and how this affects the acoustic field. Their findings were recently published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Sound levitation happens when sound waves interact and form a standing wave with nodes that can ‘trap’ a particle. Gorkov’s core theory of acoustophoresis, the current mathematical foundation for acoustic levitation, makes the assumption that the particle being trapped is a sphere.