The material could replace rare metals and lead to more economical production of carbon-neutral fuels.

Scientists identify a long-sought magnetic state predicted nearly 60 years ago.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory have discovered a long-predicted magnetic state of matter called an “antiferromagnetic excitonic insulator.”

“Broadly speaking, this is a novel type of magnet,” said Brookhaven Lab physicist Mark Dean, senior author on a paper describing the research just published in Nature Communications. “Since magnetic materials lie at the heart of much of the technology around us, new types of magnets are both fundamentally fascinating and promising for future applications.”

[Stefan] from CNCKitchen wanted to make some bendy tubes for a window-mountable ball run, and rather than coming up with some bent tube models, it seemed there might be a different way to achieve the desired outcome. Starting with a simple tube model designed to be quickly printed in vase mode, he wrote a Python script which read in the G-Code, and modified it allow it to be bent along a spline path.

Vase mode works by slowly ramping up the Z-axis as the extruder follows the object outline, but the slicing process is still essentially the same, with the object sliced in a plane parallel to the bed. Whilst this non-planar method moves the Z-axis in sync with the horizontal motion (although currently limited to only one plane of distortion, which simplifies the maths a bit) it is we guess still technically a planar solution, but just an inclined plane. But we digress, non-planar in this context merely means not parallel to the bed, and we’ll roll with that.

[Stefan] explains that there are quite a few difficulties with this approach. The first issue is that on the inside of the bend, the material flow rate needed to be scaled back to compensate. But the main problem stems from the design of the extruder itself. Intended for operating parallel to the bed, there are often a few structures in the way of operating at an angle, such as fan mounts, and the hotend itself. By selecting an appropriate machine and tweaking it a bit, [Stefan] managed to get it to work at angles up to 30 degrees off the horizontal plane. One annoyance was that the stock nozzle shape of his E3D Volcano hotend didn’t lend itself to operating at such an inclination, so he needed to mount an older V6-style tip with an adapter. After a lot of tuning and fails, it did work and the final goal was achieved! If you want to try this for yourselves, the code for this can be found on the project GitHub.

The unsung star of Jurassic Park was a mosquito frozen in amber. While you can’t really extract blood from specimens like that, you could be transported back in time if you looked at a specimen of fossilized tree sap and found a 110 million-year-old lizard staring back at you.

Creatures get trapped in amber all the time, but most prehistoric finds are insects. Amber is a great material for preserving arthropods because of their already tough shells that will hold on even if the insides disintegrate. But what about a lizard? Retinosaurus hkamentiensis is a new extinct species of lizard that was unexpectedly found trapped in Burmese amber. No one expected an entire reptile to be preserved so well, from its scaly skin down to its skeleton.

What are now the empty eyes of Retinosaurus may have once seen dinosaurs or giant ferns or dragonflies the size of your head. It was determined to be a juvenile that ran into a sticky situation when it ran into a glob of tree amber that it couldn’t escape. It was so well preserved that paleontologist Andrej Čerňanský of Comenius University and his team, who recently published a study in Scientific Reports, approached the prehistoric lizard almost as if it were alive.

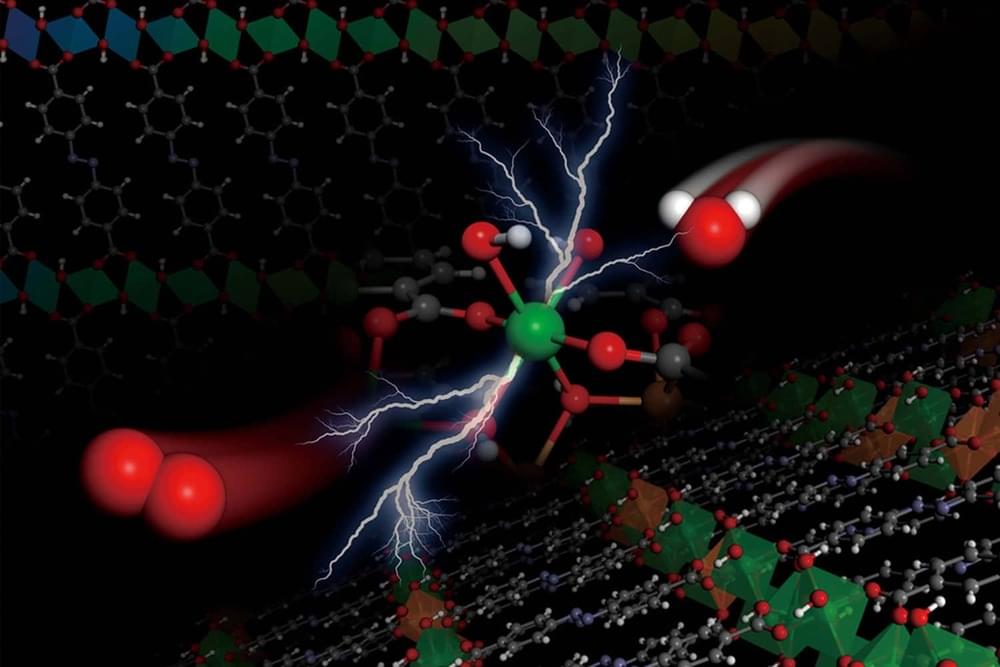

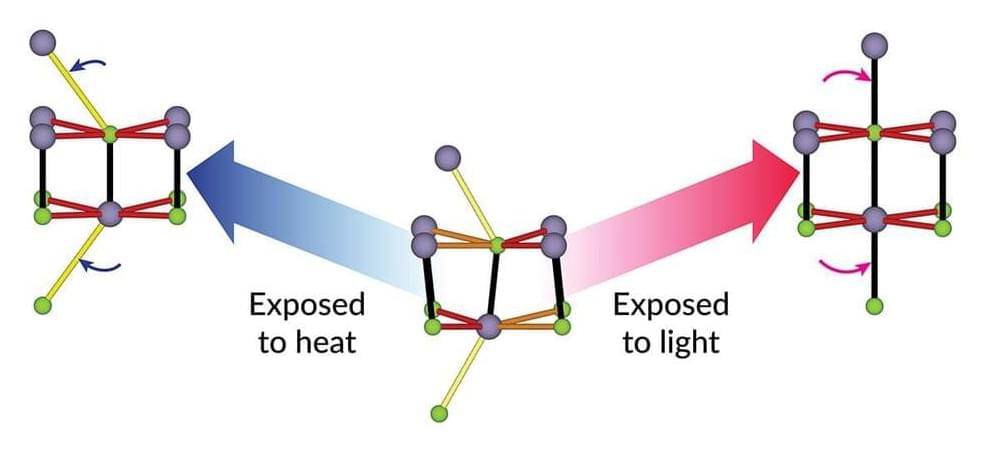

Thermoelectric materials convert heat to electricity and vice versa, and their atomic structures are closely related to how well they perform.

Now researchers have discovered how to change the atomic structure of a highly efficient thermoelectric material, tin selenide, with intense pulses of laser light. This result opens a new way to improve thermoelectrics and a host of other materials by controlling their structure, creating materials with dramatic new properties that may not exist in nature.

“For this class of materials that’s extremely important, because their functional properties are associated with their structure,” said Yijing Huang, a Stanford University graduate student who played an important role in the experiments at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. “By changing the nature of the light you put in, you can tailor the nature of the material you create.”

And it’s a perfect fit. Enamel is an incredible material. It’s sturdy enough so that humans can chew but flexible enough that it doesn’t crack with every bite. Unfortunately, humans can not regenerate it. Once lost or damaged, it’s gone forever.

OpenAI’s chief scientist has admitted what we all fear — that artificial intelligence may be gaining consciousness.

But the benefits of fusion reaction are immense. Apart from generating much more energy, fusion produces no carbon emissions, the raw materials are in sufficient supply, produces much less radioactive waste compared to fission, and is considered much safer.

Over the years, scientists have been able to draw up the plan for a fusion nuclear reactor. It is called ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) and is being built in southern France with the collaboration of 35 countries, including India which is one of the seven partners, alongside the European Union, the United States, Russia, Japan, South Korea and China.