Liquid crystal is a state of matter that exhibits properties of both liquid and solid. It can flow like a liquid, while its constituent molecules are aligned as in a solid. Liquid crystal is widely used nowadays, for example, as a core element of LCD devices.

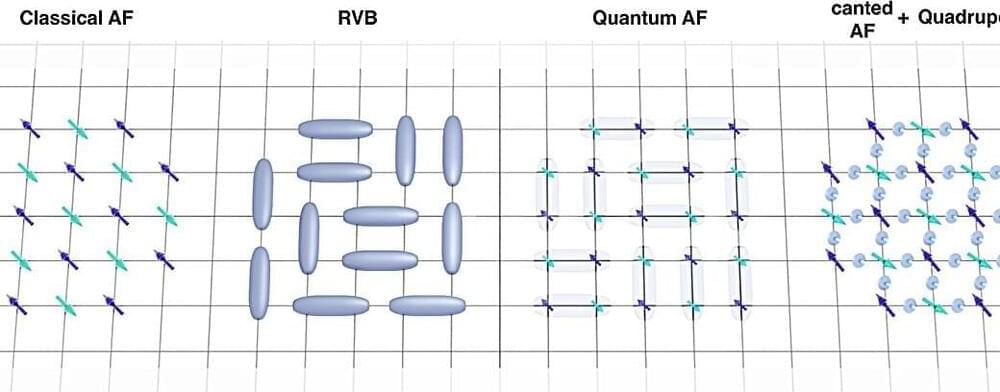

The magnetic analog of this kind of material is dubbed the “spin-nematic phase,” where spin moments play the role of the molecules. However, it has not yet been directly observed despite its prediction a half-century ago. The main challenge stems from the fact that most conventional experimental techniques are insensitive to spin quadrupoles, which are the defining features of this spin-nematic phase.

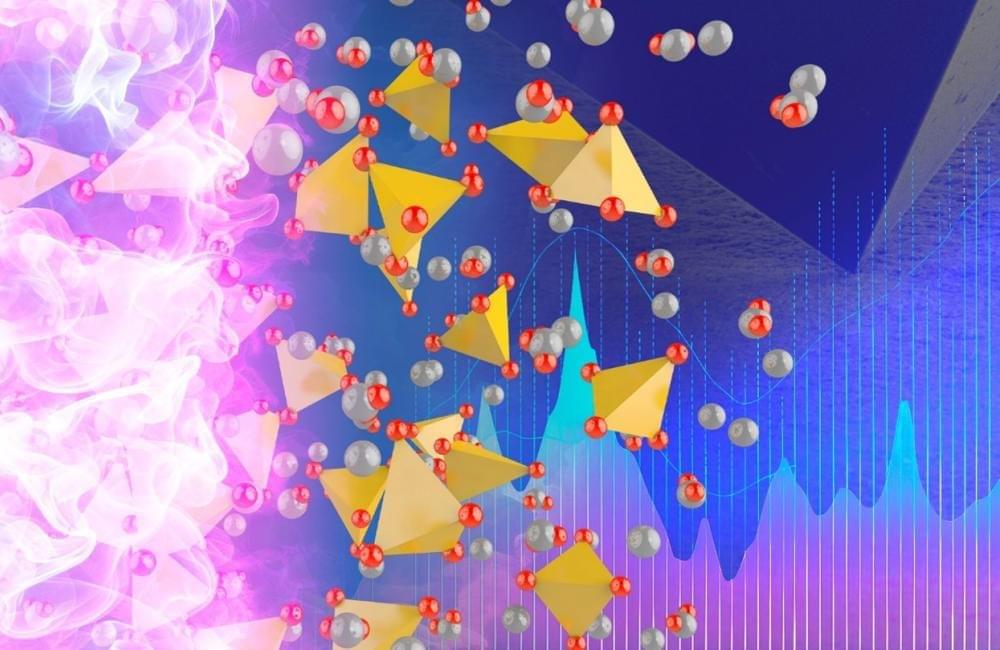

But now, for the first time in the world, a team of researchers led by Professor Kim Bumjoon at the IBS Center for Artificial Low-Dimensional Electronic Systems in South Korea has succeeded at directly observing spin quadrupoles. This work was made possible through remarkable achievements over the last decades in synchrotron facility development.