Chinese space has been a very hot topic in recent years. Other than the impressive space exploration missions (Tiangong, Chang’e…), the interest for China is also due to the recent opening up of this industry to private investments, which has led to a leap in the number of space start-ups. These start-ups, supported by venture capital heavy-weights are covering the entire space industrial chain: launchers, satellite platforms, satellite subsystems, satellite services, ground segment, etc.

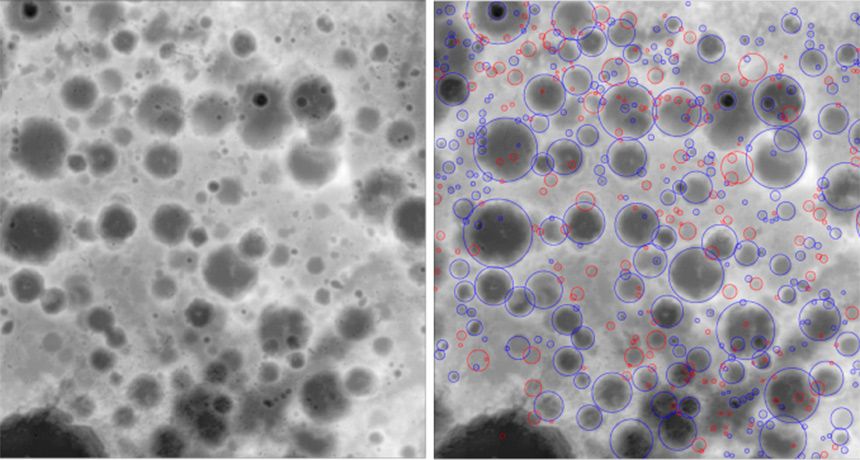

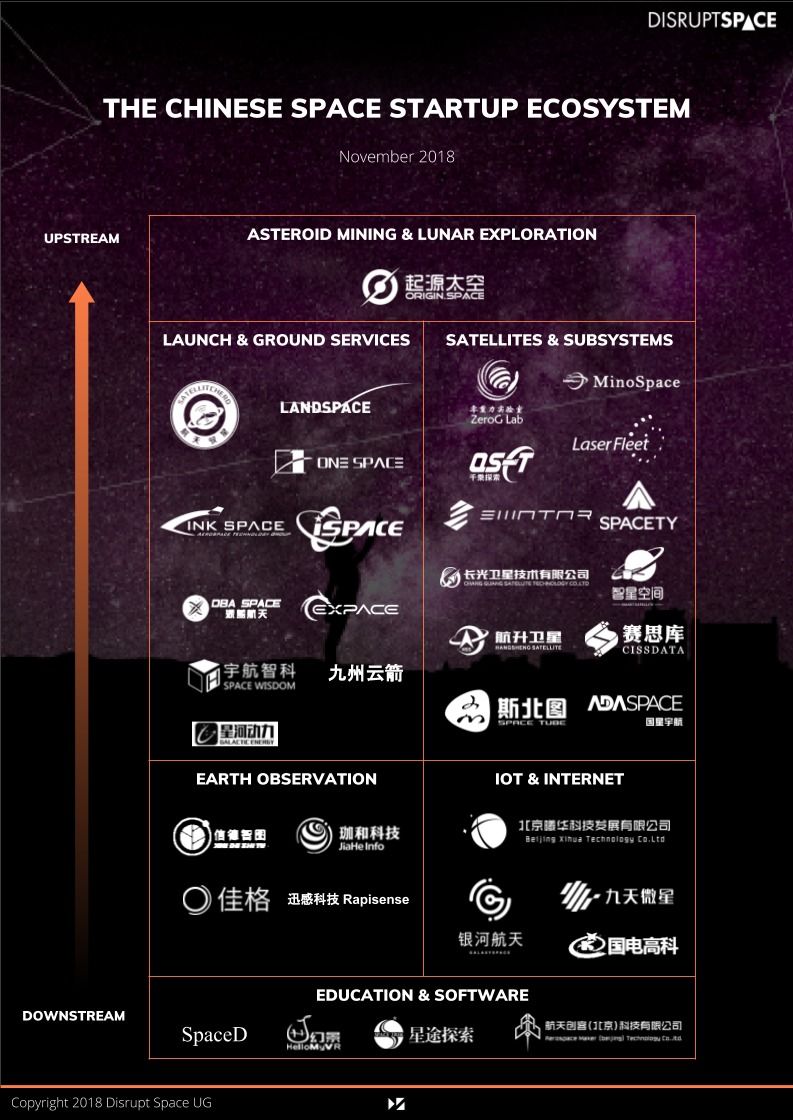

The number of space start-ups on the other hand, is a debated question. Chen Lan estimated in November 2018 that there were over 100 Chinese space start-ups [1]. FutureAerospace, a Beijing-based think-tank, sets the number at around 60, at the same period [2]. Other space watchers have suggested 80 such as in [3]. However, how this count is made is rarely detailed (how do we define a “NewSpace company”?), and very few lists are available at the time of writing, if any. Up to now, only Disrupt Space, a start-up which plans to build a global space entrepreneurial community, has undertaken the establishment of a list, which sets the count at 35 Chinese space start-ups (see map below).

Fig. 1 – Disrupt Space’s Chinese Space Start-up Mapping in November 2018 [4]