This starts with Tyson’s deathism quote, but I’m still a fan. I do wonder if he’ll take a treatment when he sees everyone else rejuvenating around him.

Category: life extension – Page 312

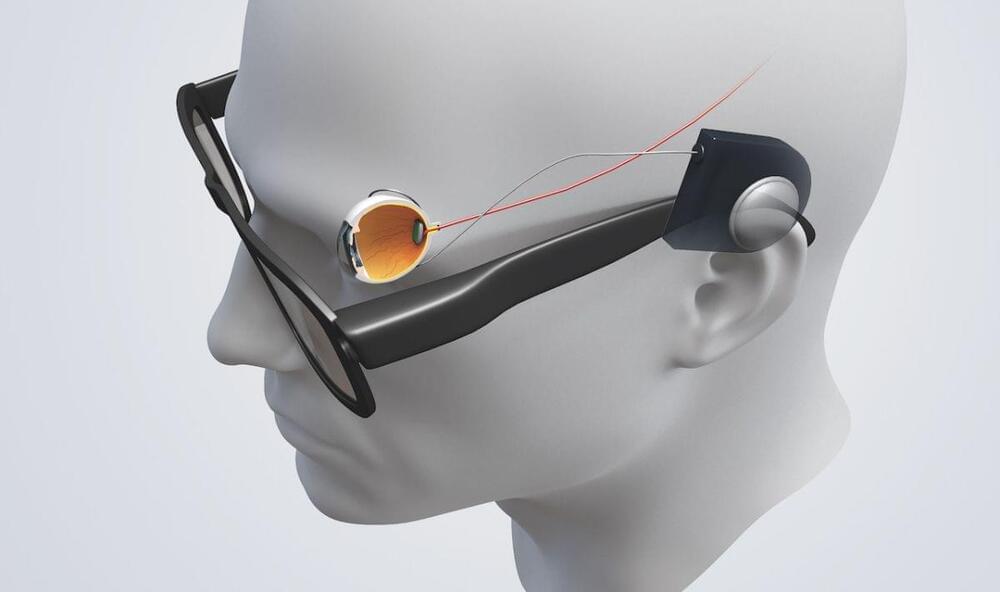

Bionic eyes: How tech is replacing lost vision

This technology has to translate images into something the human brain can understand. Click the numbers in the interactive image below to find read about how this works.

There are a whole range of conditions, some which are picked up due to the aging process and others which may be inherited, that can cause sight deterioration.

Bionic eyes work by ‘filling in the blanks’ between what the retina perceives and how it is processed in the brain’s visual cortex, that breakdown occurs in conditions which impact the retina. It is largely these conditions which bionic eyes could help treat.

Scientists “Elated”

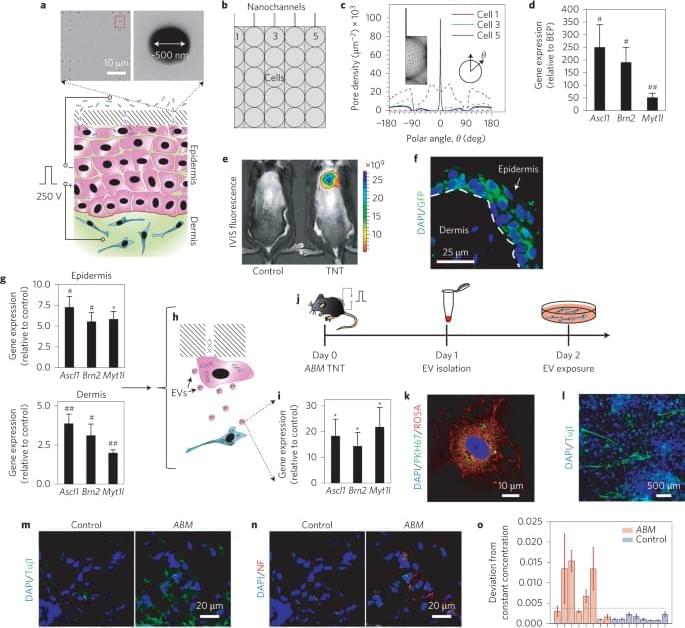

An international team of researchers claim to have slowed the signs of aging in mice by resetting their cells to younger states, using a genetic treatment.

To the scientists, The Guardian reports, it’s a breakthrough in cell regeneration and therapeutic medicine that doesn’t seem to cause any unexpected issues in mice.

“We are elated that we can use this approach across the life span to slow down aging in normal animals,” said Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, Salk Institute professor and co-corresponding author of a new study published in the journal Nature Aging, in a statement. “The technique is both safe and effective in mice.”

Dr. Kara Spiller, PhD — Immunomodulatory Biomaterials In Regenerative Medicine — Drexel University

Immunomodulatory Biomaterials In Regenerative Medicine — Dr. Kara Spiller-Geisler, Ph.D., Drexel University School of Biomedical Engineering, Science and Health Systems.

Dr. Kara Spiller, PhD (https://drexel.edu/biomed/faculty/core/SpillerKara/) is Associate Professor in the Biomaterials and Regenerative Medicine Laboratory at Drexel University, in Philadelphia.

Dr. Spiller received her bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in biomedical engineering from Drexel University where she conducted her doctoral research in the design of semi-degradable hydrogels for the repair of articular cartilage in the Biomaterials and Drug Delivery Laboratory at Drexel, and in the Shanghai Key Tissue Engineering Laboratory of Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

After completing her PhD, when she received the award for Most Outstanding Doctoral Graduate: Most Promise to Enhance Drexel’s Reputation, she conducted research in the design of scaffolds for bone tissue engineering as a Fulbright Fellow, in the Biomaterials, Biodegradables, and Biomimetics (the 3Bs) Research Group at the University of Minho in Guimaraes, Portugal. She also worked as a Postdoctoral Scientist at Columbia University.

Dr. Spiller is currently conducting research in the design of immuno-modulatory biomaterials, particularly for bone tissue engineering. Her research interests include cell-biomaterial interactions, biomaterial design, and international engineering education.

CRISPR On-Off Switch Will Help Unlock the Secrets of Our Immune System

Can we turn up—or dial down—their fervor by tweaking their genes?

Enter a new kind of CRISPR. Known mostly as a multi-tool to cut, snip, edit, or otherwise kneecap an existing gene, this version—dubbed CRISPRa—forcibly turns genes on. Optimized by scientists at Gladstone Institutes and UC San Francisco, the tool is counterbalanced by CRISPRi—“i” for “interference,” which, you guessed it, interferes with the gene’s expression.

Though previously used in immortal cells grown in labs, this is the first time these CRISPR tools are rejiggered for cells extracted from our bodies. Together, the tools simultaneously screened nearly 20,000 genes in T cells isolated from humans, building a massive genetic translator—from genes to function—that maps how individual genes influence T cells.

Cellular ‘Rejuvenation’ Experiment in Mice Reverses Signs of Aging, Scientists Say

With age comes experience. And with experience come sore backs, tired bones, and increased risks from a large number of diseases.

Scientists have long been trying figure out how to stop these aches and pains in our twilight years, and to make us live longer and healthier lives at the same time.

While it’s likely a long way off from being ready for humans, a new study investigating the long-term ‘partial reprogramming’ of cells in mice appears to have produced some very intriguing results.