A new and extensive interview I did at New Atlas, including ideas about my #libertarian California Governor run. Libertarianism has many good ideas, but two core concepts are the non-aggression principle (NAP) and protection of private property rights—both of which I believe can be philosophically applied to the human body (and the body’s inevitable transhuman destiny of overcoming disease and decay with science and technology):

Zoltan Istvan is a transhumanist, journalist, politician, writer and libertarian. He is also running for Governor of California for the Libertarian Party on a platform pushing science and technology to the forefront of political discourse. In recent years, the movement of transhumanism has moved from a niche collection of philosophical ideals and anarcho-punk gestures into a mainstream political movement. Istvan has become the popular face of this movement after running for president in 2016 on a dedicated transhumanist platform.

We caught up with Istvan to chat about how transhumanist ideals can translate into politics, how technology is going to change us as humans and the dangers in not keeping up with new innovations, such as genetic editing.

New Atlas: How does transhumanism intersect with politics?

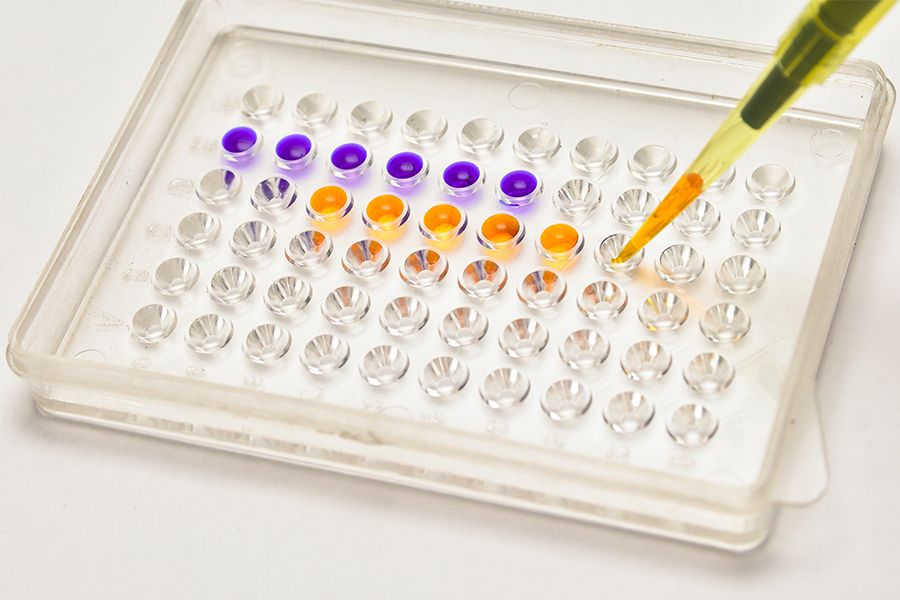

Istvan: For me you can never make any headway in the universe, or on planet Earth, if you don’t involve politics because so much money for innovation or research and development comes from the government and so many laws about what you can do. Genetic editing, chip implants, can you get a brain implant that makes you smarter than other people? These things are often directed by the government determining whether it’s illegal or not. You can either be thrown in jail or not thrown in jail – so you must have a political footprint, you must have attorneys on the ground, you must have that kind of legal position that can explain things in terms that a government will understand.