The most expedient way to produce the algorithms you need for a new class of computer that works like the brain, its engineers are discovering, is through a Darwinian exercise in natural selection.

After controlling for various factors — such as participants’ age, sex, smoking status and activity level — the researchers found that taking glucosamine/chondroitin every day for a year or longer was associated with a 39 percent reduction in all-cause mortality.

It was also linked to a 65 percent reduction in cardiovascular-related deaths. That’s a category that includes deaths from stroke, coronary artery disease and heart disease, the United States’ biggest killer.” “He explains that because this is an epidemiological study — rather than a clinical trial — it doesn’t offer definitive proof that glucosamine/chondroitin makes death less likely. But he does call the results “encouraging.””.

Glucosamine supplements may reduce overall mortality about as well as regular exercise does, according to a new epidemiological study from West Virginia University.

“Does this mean that if you get off work at five o’clock one day, you should just skip the gym, take a glucosamine pill and go home instead?” said Dana King, professor and chair of the Department of Family Medicine, who led the study. “That’s not what we suggest. Keep exercising, but the thought that taking a pill would also be beneficial is intriguing.”

He and his research partner, Jun Xiang — a WVU health data analyst — assessed data from 16,686 adults who completed the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1999 to 2010. All of the participants were at least 40 years old. King and Xiang merged these data with 2015 mortality figures.

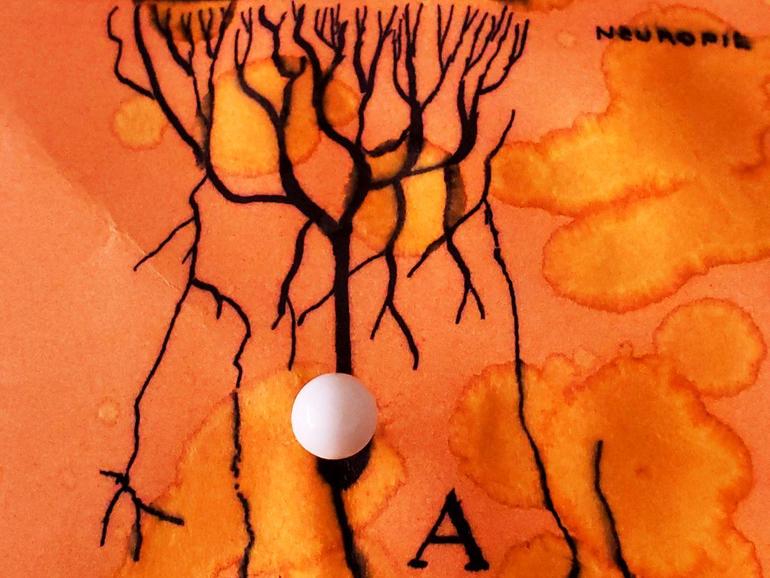

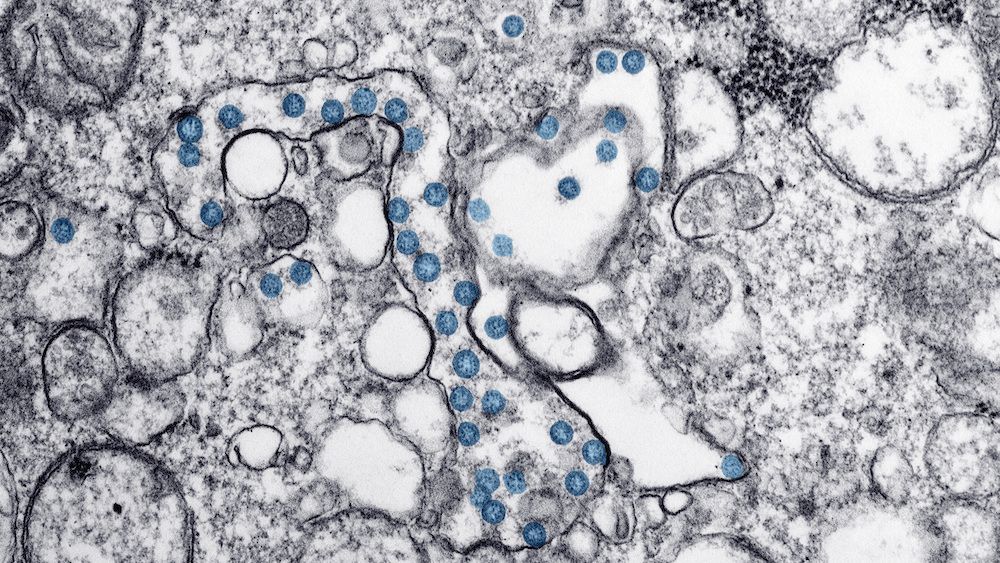

MHRA will only become fully independent on 1 January 2021, following Brexit, but U.K. regulations allow it to grant authorizations on an emergency basis. The United Kingdom has bought 40 million doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine—enough for 20 million people—and health secretary Matt Hancock today announced the first 800,000 doses will be available next week. The rollout will prioritize health workers as well as the elderly and other vulnerable populations, but the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation has yet to offer its final guidance on the exact priorities.

Russia on 11 August allowed its COVID-19 vaccine, developed by the Gamaleya Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology, to be used on certain groups of people, and China has granted emergency use authorizations (EUAs) for several vaccines and has already vaccinated hundreds of thousands of people with them. A few other countries, including the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, have issued an EUA for one of the Chinese vaccines, produced by Sinopharm.

The Pfizer vaccine, whose key ingredient is messenger RNA that encodes the spike protein of the pandemic coronavirus, was found to have 95% efficacy, a clinical trial measurement of effectiveness, in a phase III trial in 43,000 people. But it presents logistical challenges for a widescale and rapid rollout, as it requires storage at −70°C. The lesser demands of other vaccines—including a candidate developed by the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca—mean they will likely still play an important role in providing vaccinations for the whole U.K. population—and for global coverage, according to Michael Head, a global health researcher at the University of Southampton, “but, for now, this is wonderful news to wake up to.”

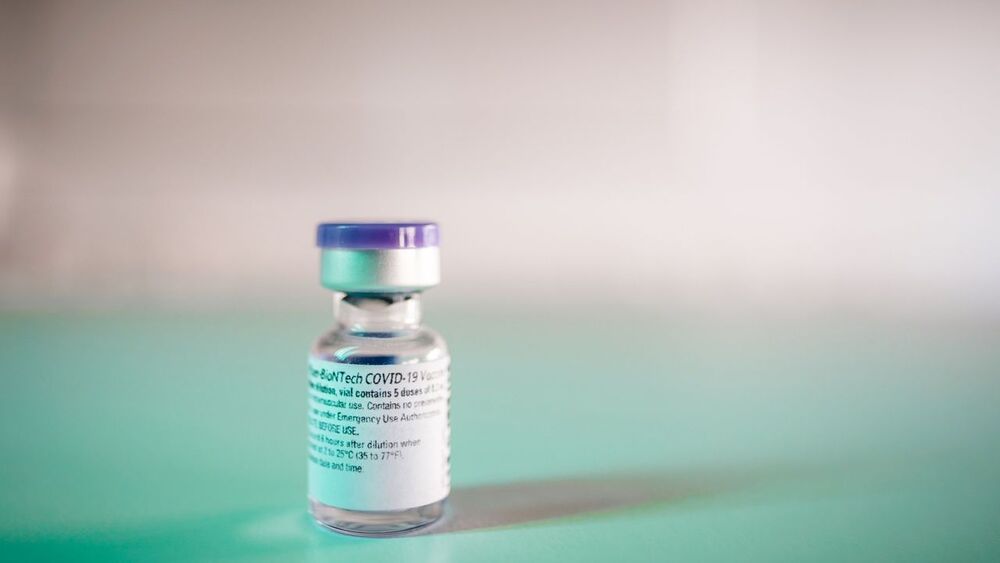

Artificial intelligence (AI) has solved one of biology’s grand challenges: predicting how proteins curl up from a linear chain of amino acids into 3D shapes that allow them to carry out life’s tasks. Today, leading structural biologists and organizers of a biennial protein-folding competition announced the achievement by researchers at DeepMind, a U.K.-based AI company. They say the DeepMind method will have far-reaching effects, among them dramatically speeding the creation of new medications.

Shockingly, Carroll notes that if our own Earth had formed just one percent farther away from the Sun, it would have suffered a runaway glaciation. By contrast, one percent further in and Earth would have suffered a runaway greenhouse and the fate that befell present-day Venus. “The habitable zone is a planetary tightrope,” writes Carroll.

However, the book does cover the possibility that super-earths and/or gas giant planets that lie in their parent stars’ habitable zones might also harbor planet-sized moons. As the book notes, it’s an idea that Hollywood director James Cameron’s embraced in his ground-breaking movie “Avatar.”

“Envisioning Exoplanets” also offers the reader capsule summaries of the various detection techniques that astronomers have used through the years to remotely explore and characterize these far-flung worlds.

More than 100 SARS-CoV-2 infected mink may have escaped from Danish fur farms, raising the risk that these escapees could spread the novel coronavirus to wild animals, creating a new reservoir for the virus, The Guardian reported.

“Every year, a few thousand mink escape,” and this year, an estimated 5 percent of these escaped animals may have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, Sten Mortensen, veterinary research manager at the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration, told The Guardian.

These mink may be spreading the coronavirus to wild animals, even as millions of mink still on farms are being culled to prevent spread of the virus.

Welcome back to our series on Martian colonization! In Part I, we looked at the challenges and benefits of colonization. In Part II, we looked at what it would take to transport people to and from Mars. In Part III, we looked at how people could live there. Today, we will address the question of how people could establish an industrial base there.

If we intend to “go interplanetary” and establish a colony on Mars, we need to know how to address the long-term needs of the colonists. In addition to shelter, air, water, food security, and radiation shielding, the people will need to create an economy of sorts. The question is, what kind of industry would Mars support?

There’s Gold in Them Thar’ Hills!

One of the main reasons why Mars is considered an attractive location for a colony is the similarities it has to Earth. Like Earth, it’s a terrestrial (aka. rocky) planet that’s composed primarily of metals and silicate minerals, which are differentiated between a metallic core and a silicate mantle and crust.

AI, Genetics, and Health-Tech / Wearables — 21st Century Technologies For Healthy Companion Animals.

Ira Pastor ideaXme life sciences ambassador interviews Dr. Angela Hughes, the Global Scientific Advocacy Relations Senior Manager and Veterinary Geneticist at Mars Petcare.

The global petcare industry is significantly expanding, with North America sales alone expected to hit US $300 billion by 2025. And while we may associate the Mars Corporation, the world’s largest candy company, with leading confectionary brands like Milky Way, M&M’s, Skittles, Snickers, Twix, etc. They also happen to be one of the world’s largest companies in pet care as well.

Dr. Angela Hughes, is the Global Scientific Advocacy Relations Senior Manager & Veterinary Geneticist at Mars Petcare. Dr. Hughes is both Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, and a PhD with a focus in Canine Genetics, both from the University of California, Davis. Dr. Hughes also serves as Veterinary Genetics Research Manager of Wisdom Health, a business unit of Mars Petcare, which has developed state-of-the-art genetic tests for companion animals, leading to revolutionary personalized petcare. She also serves as a Veterinary Geneticist of Hughes Veterinary Consulting, focused on small animal and equine genetics and with a special interest in small animal reproduction and pediatrics.

Dr Hughes is published in multiple academic journals, including the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association and has contributed chapters for publication in Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice: Pediatrics and Large Animal Internal Medicine.

A recent study published Tuesday in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine found that most Americans are still susceptible to COVID-19.

According to the study, researchers studied the blood samples of 177,919 Americans across the nation, D.C., and Puerto Rico between July 27 and Sept. 24. They found that fewer than 10% of the people had detectable COVID antibodies.

“In this U.S. nationwide seroprevalence cross-sectional study, we found that as of September 2020, most persons in the US did not have detectable SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, and seroprevalence estimates varied widely by jurisdiction,” the authors concluded. “Continued biweekly testing of sera collected by commercial laboratories will allow for assessment of the changing epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 in the U.S. in the coming months. Our results reinforce the need for continued public health preventive measures, including the use of face masks and social distancing, to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the U.S.”