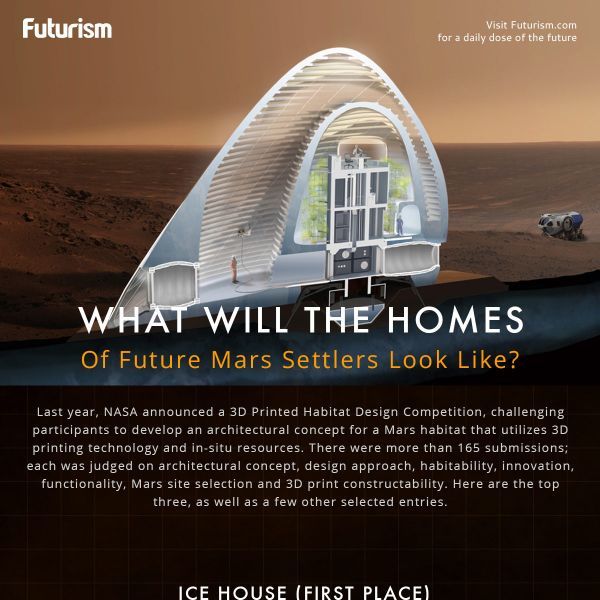

In a world of economic scarcity, public housing has become essential for sheltering our species’ most vulnerable populations. Interestingly, the island city-state of Sinagpore having a unique approach to public housing, with 80% of the resident population living in government buildings and, more than that, the small nation implemented some housing practices that the United States has sometimes been too afraid to tackle when it comes to public housing: socioeconomically integrated public developments. Now, Singapore is moving beyond these important strategies to novel methods of construction, namely 3D printing.

The Singapore Centre for 3D Printing, established with $107.7 million in government and industry funding, is in the process of working with a company to test the feasibility of 3D printing public housing units storey by storey, off-site, before assembling them at their destination. Professor Chua Chee Kai, Executive Director of the Singapore Centre for 3D Printing tells GovInsider, “The idea is to print them maybe a unit at a time. So if you have a 10 storey building, you will probably do one storey at a time. These will be transported to the construction site where they will be stacked up like lego.”