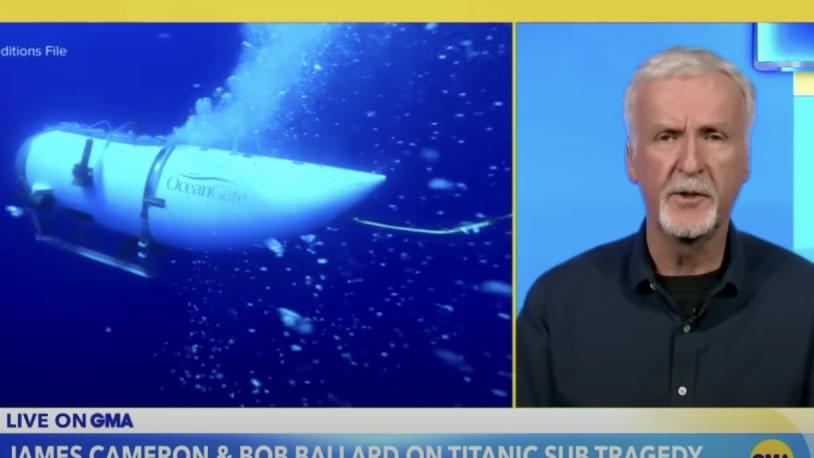

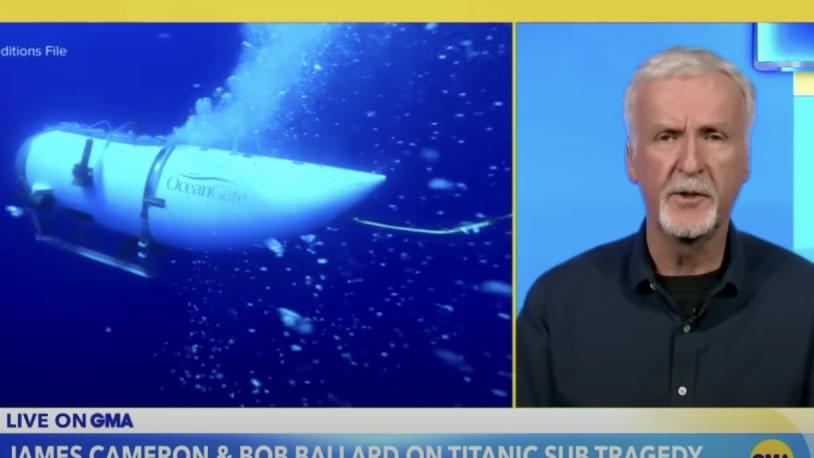

Director and oceanographer James Cameron said Friday that the design of the imploded Titan submersible was “critically flawed,” calling the construction of the vessel an “insidious” mistake.

For the first time, U.S. regulators on Wednesday approved the sale of chicken made from animal cells, allowing two California companies to offer “lab-grown” meat to the nation’s restaurant tables and eventually, supermarket shelves.

The Agriculture Department gave the green light to Upside Foods and Good Meat, firms that had been racing to be the first in the U.S. to sell meat that doesn’t come from slaughtered animals — what’s now being referred to as “cell-cultivated” or “cultured” meat as it emerges from the laboratory and arrives on dinner plates.

The move launches a new era of meat production aimed at eliminating harm to animals and drastically reducing the environmental impacts of grazing, growing feed for animals and animal waste.

Analysts are trying to estimate the value of Tesla’s Supercharger network as the NACS connector becomes the North American standard and could widen Tesla’s charging lead.

One of the top Tesla analysts believes it could be worth more than $100 billion.

The Supercharger network is the only global EV fast-charging network, and in North America, it is by far the most extensive and reliable.

“If someone is a good bulls—er, they are likely quite smart,” says Martin Turpin, a graduate student at the Reasoning and Decision Making Lab at the Unversity of Waterloo and co-lead on the study recently published in the scientific journal Evolutionary Psychology.

Turpin and his colleagues found that people who are better at producing believable explanations for concepts, even when those explanations aren’t based on fact, typically score better on intelligence tests than those who struggle to “bulls—,” as the study puts it.” However, it is not the case that those who are not good bulls—ers are less intelligent,” Turpin says.

Apple today introduced the first version of the visionOS software, debuting the visionOS 1.0 Developer Beta. The introduction of the beta comes as Apple has announced the launch of the visionOS software development kit (SDK) that will allow third-party developers to build apps for the Vision Pro headset.

The SDK can be accessed through Xcode 15 beta 2, and while developers do not have access to the Vision Pro headset itself as of yet, Apple will begin allowing testing starting next month.

The future of clippy and toy makers is promising 👌 😀 😄.

As Microsoft eagerly adds Chat-GPT to Bing, Word, Edge, and dozens of other products, I can’t help myself from thinking of Clippy. The old assistant could be seen as a precursor to modern, collaborative AI. Clearly, someone else had the same thought, but they actually did something with it.

Roboticist David Packman created an animatronic Clippy that answers voice prompts using Chat-GPT. Like a Alexa or Siri, it listens for a wake word (“Hey, Clippy”) and responds accordingly. Voice prompts and Clippy’s responses are processed through Azure Speech Services, and the whole thing runs on a Raspberry Pi computer.