Dr. Jordan B. Peterson and Andrew Huberman discuss neurology, the way humans and animals react to specific stimuli, and how this knowledge can be utilized for personal growth.

Category: futurism – Page 444

Liquid crystal elastomers make morphing fabric

New type of fibre reversibly changes its shape in response to temperature and can be spun into threads to make entire morphing garments. Potential applications for the technology include compression garments for post-surgical recovery, adaptive architectural interiors and even clothing that “hugs” its wearer on activation.

From ‘liquid lace’ to the ‘Drop Medusa,’ researchers compete for the best image of fluid flow

Each year at its annual meeting, the American Physical Society’s Division of Fluid Dynamics sponsors a contest for the best images in a variety of categories, all related to the flow of fluids.

This year’s Gallery was presented at the Division’s 76th meeting in November in Washington, D.C., with 12 artistic videos and images being selected in four different categories. Here are some of the winners.

Paul Churchland’s Eliminative Materialism

FOR ACADEMIC PURPOSES ONLY.

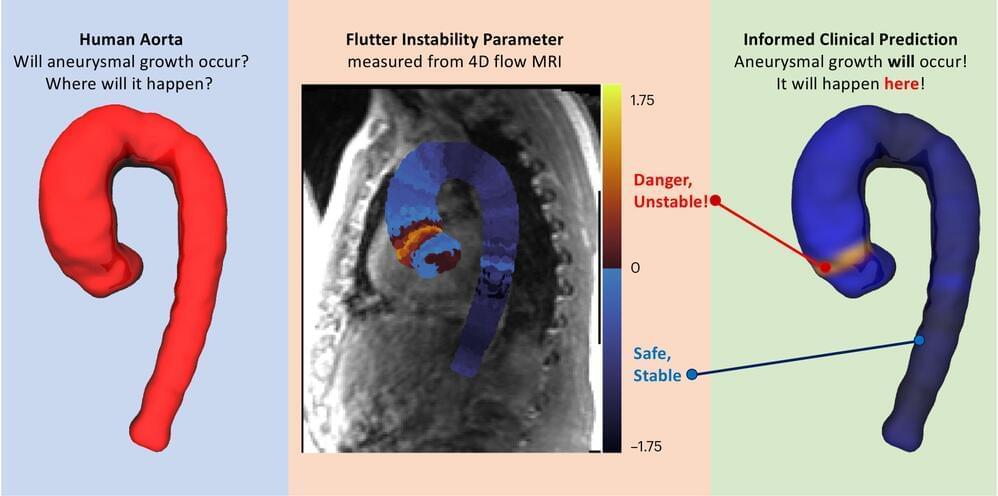

Unstable ‘fluttering’ predicts aortic aneurysm with 98% accuracy

Northwestern University researchers have developed the first physics-based metric to predict whether or not a person might someday suffer an aortic aneurysm, a deadly condition that often causes no symptoms until it ruptures.

In the new study, the researchers forecasted abnormal aortic growth by measuring subtle “fluttering” in a patient’s blood vessel. As blood flows through the aorta, it can cause the vessel wall to flutter, similar to how a banner ripples in the breeze. While stable flow predicts normal, natural growth, unstable flutter is highly predictive of future abnormal growth and potential rupture, the researchers found.

Called the “flutter instability parameter” (FIP), the new metric predicted future aneurysm with 98% accuracy on average three years after the FIP was first measured. To calculate a personalized FIP, patients only need a single 4D flow magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

Airbnb boss called his CEO network asking if they could hire any of the 1,900 staff he laid off

As a result, he’s built a network of peers who can relate to his challenges, name-dropping Spotify CEO Daniel Ek, who had appeared on the same podcast just a few weeks before, as one of them.

“Daniel Ek doesn’t know the Brian before Airbnb,” Chesky explained. “So maybe he doesn’t know ‘the real me’…but he does know a different ‘real me’ that my childhood friends can’t know, because high school and college friends can’t possibly know what it’s like for me to go through what I’m going through.

I can tell it to them, and they can have compassion, but they can’t possibly know what I’m talking about. But Daniel can.