Category: futurism – Page 1,242

Futuristic “Living” Electronic Clothes and Walls Unveiled

The future of clothing unfolds at this year’s Consumer Electronics Show with the unveiling of an e-ink dress and much more!

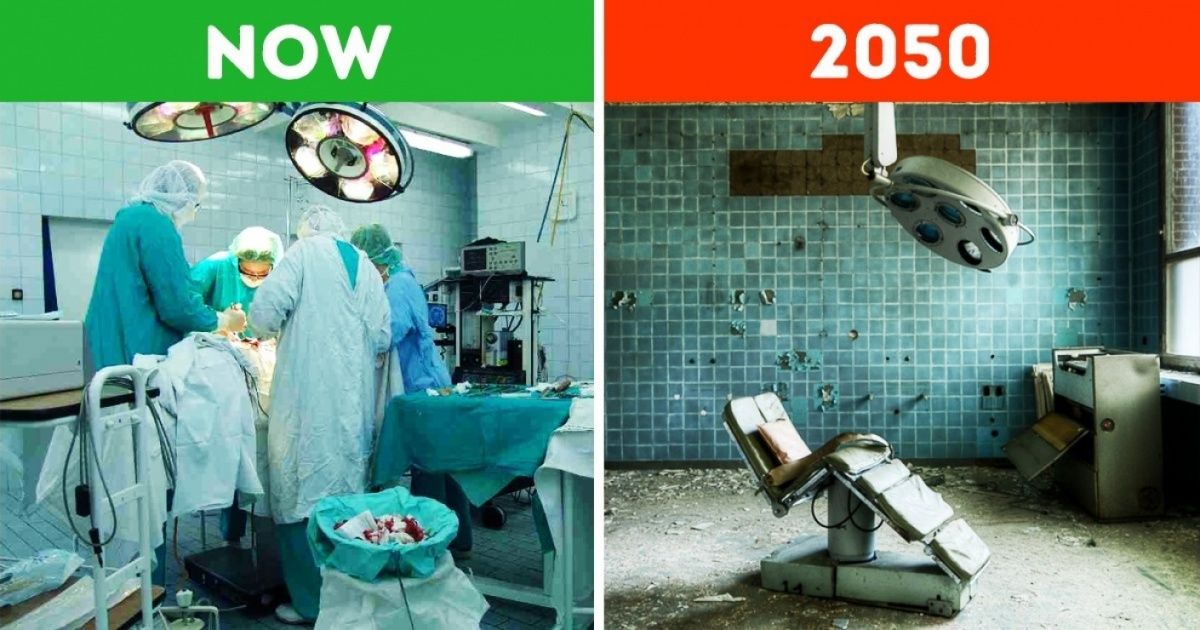

12 Everyday Things That Will Soon Disappear

Landlines disappeared, and so did videotapes. With neverending technological advancements, there are a lot of other things that will go out of fashion or become good for nothing in the near future.

Bright Side rounded up a few things that you can’t imagine your life without right now, but they might not be familiar to the next generation at all. This list might be surprising to you as it contains some of your favorite things.