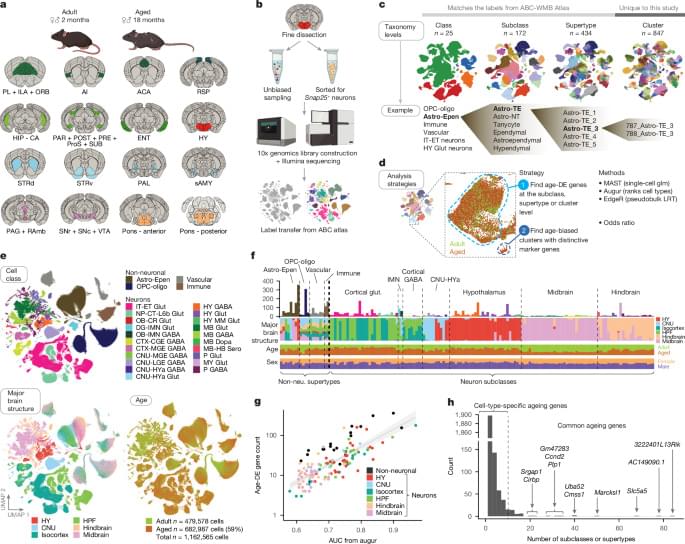

Sensitive cells: Scientists discovered dozens of specific cell types, mostly glial cells, known as brain support cells, that underwent significant gene expression changes with age. Those strongly affected included microglia and border-associated macrophages, oligodendrocytes, tanycytes, and ependymal cells.

Inflammation and neuron protection: In aging brains, genes associated with inflammation increased in activity while those related to neuronal structure and function decreased.

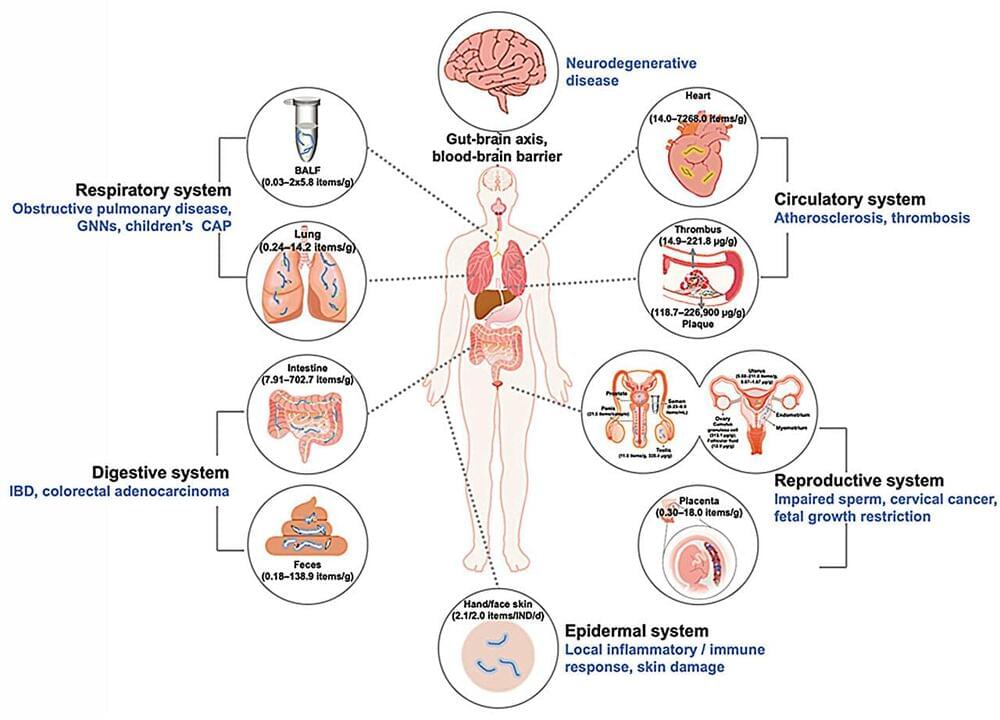

Aging hot spot: Scientists discovered a specific hot spot combining both the decrease in neuronal function and the increase in inflammation in the hypothalamus. The most significant gene expression changes were found in cell types near the third ventricle of the hypothalamus, including tanycytes, ependymal cells, and neurons known for their role in food intake, energy homeostasis, metabolism, and how our bodies use nutrients. This points to a possible connection between diet, lifestyle factors, brain aging, and changes that can influence our susceptibility to age-related brain disorders.

Brain-wide cell-type-specific transcriptomic signatures of healthy ageing in mice.

A comprehensive single-cell RNA sequencing study delineates cell-type-specific transcriptomic changes in the brain associated with normal ageing that will inform the investigation into functional changes and the interaction of ageing and disease.