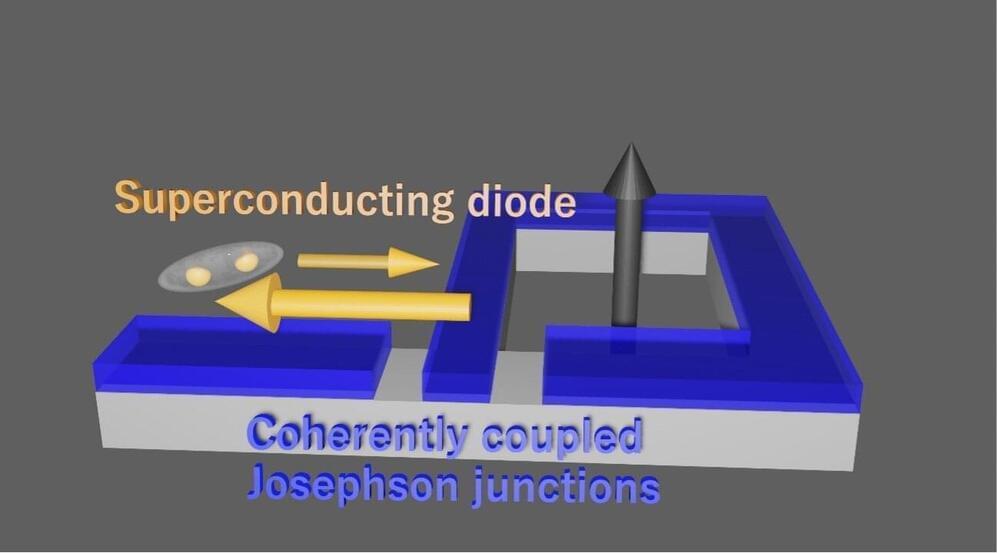

The so-called superconducting (SC) diode effect is an interesting nonreciprocal phenomenon, occurring when a material is SC in one direction and resistive in the other. This effect has been the focus of numerous physics studies, as its observation and reliable control in different materials could enable the future development of new integrated circuits.

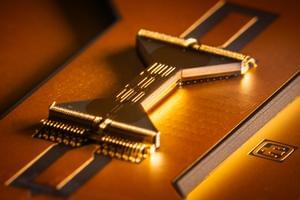

Researchers at RIKEN and other institutes in Japan and the United States recently observed the SC diode effect in a newly developed device comprised of two coherently coupled Josephson junctions. Their paper, published in Nature Physics, could guide the engineering of promising technologies based on coupled Josephson junctions.

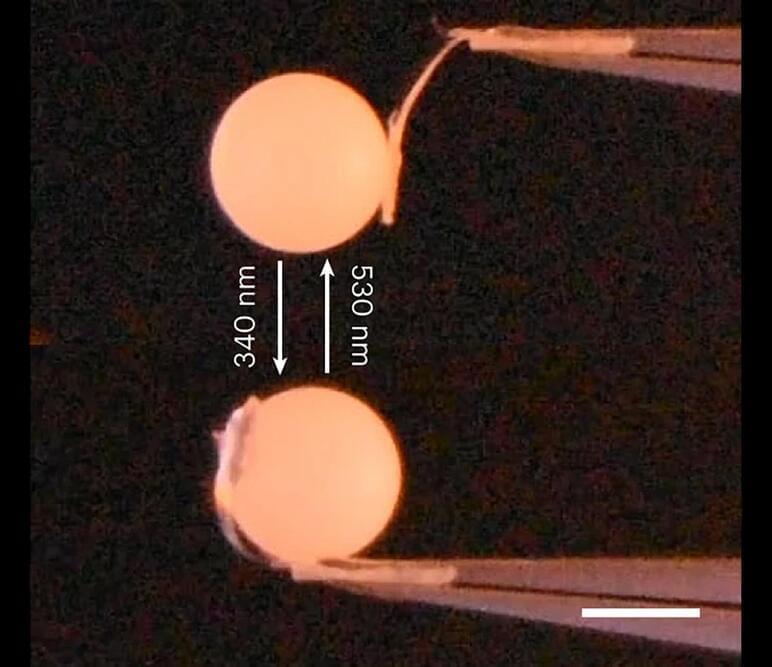

“We experimentally studied nonlocal Josephson effect, which is a characteristic SC transport in the coherently coupled Josephson junctions (JJs), inspired by a previous theoretical paper published in NanoLetters,” Sadashige Matsuo, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told Phys.org.