Microsoft warns of Scattered Spider, a financially motivated hacking crew that infiltrates firms worldwide using SMS phishing, SIM swapping, and by posing as new employees, leading to data breaches and takeovers.

Find out more:

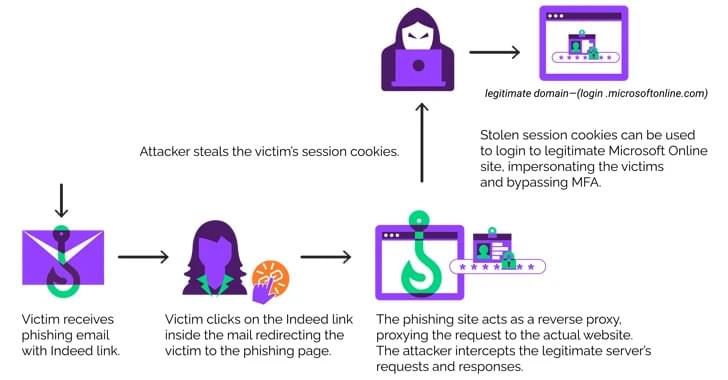

The prolific threat actor known as Scattered Spider has been observed impersonating newly hired employees in targeted firms as a ploy to blend into normal on-hire processes and takeover accounts and breach organizations across the world.

Microsoft, which disclosed the activities of the financially motivated hacking crew, described the adversary as “one of the most dangerous financial criminal groups,” calling out its operational fluidity and its ability to incorporate SMS phishing, SIM swapping, and help desk fraud into its attack model.

“Octo Tempest is a financially motivated collective of native English-speaking threat actors known for launching wide-ranging campaigns that prominently feature adversary-in-the-middle (AiTM) techniques, social engineering, and SIM swapping capabilities,” the company said.