The search for the universe’s dark matter could end tomorrow—given a nearby supernova and a little luck. The nature of dark matter has eluded astronomers for 90 years, since the realization that 85% of the matter in the universe is not visible through our telescopes. The most likely dark matter candidate today is the axion, a lightweight particle that researchers around the world are desperately trying to find.

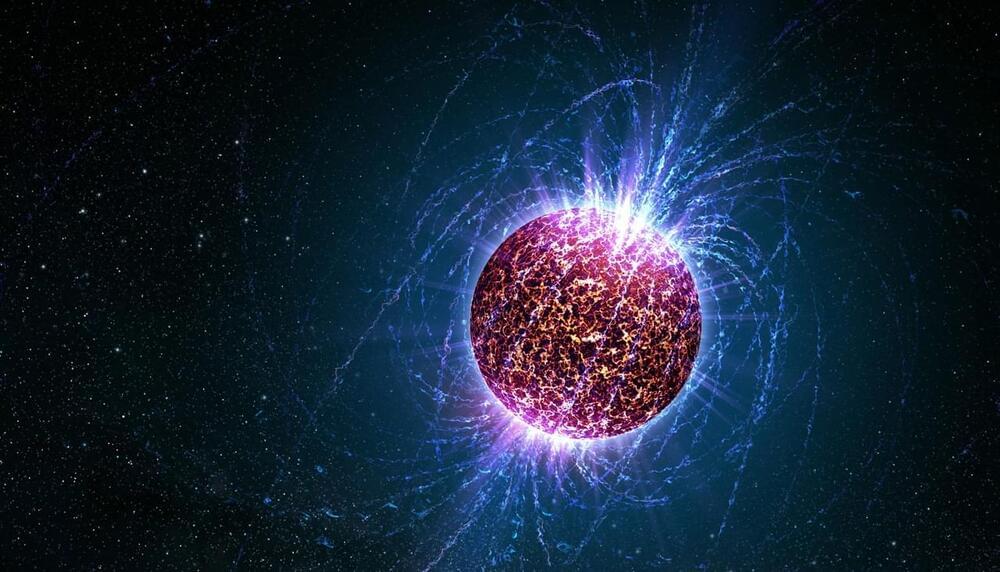

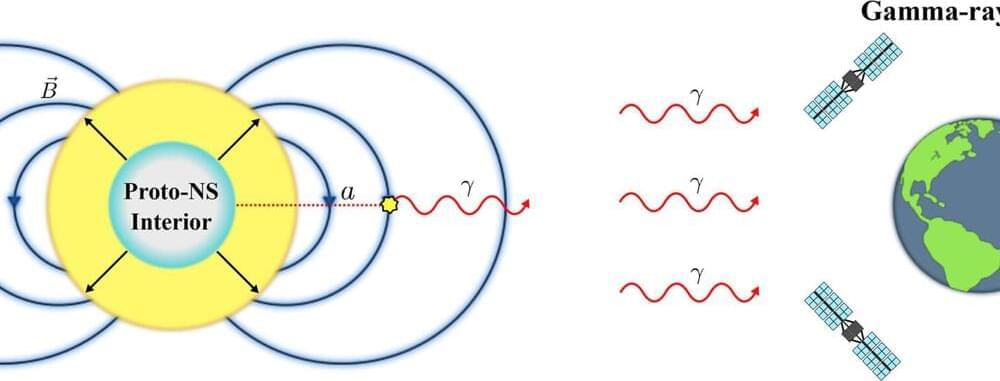

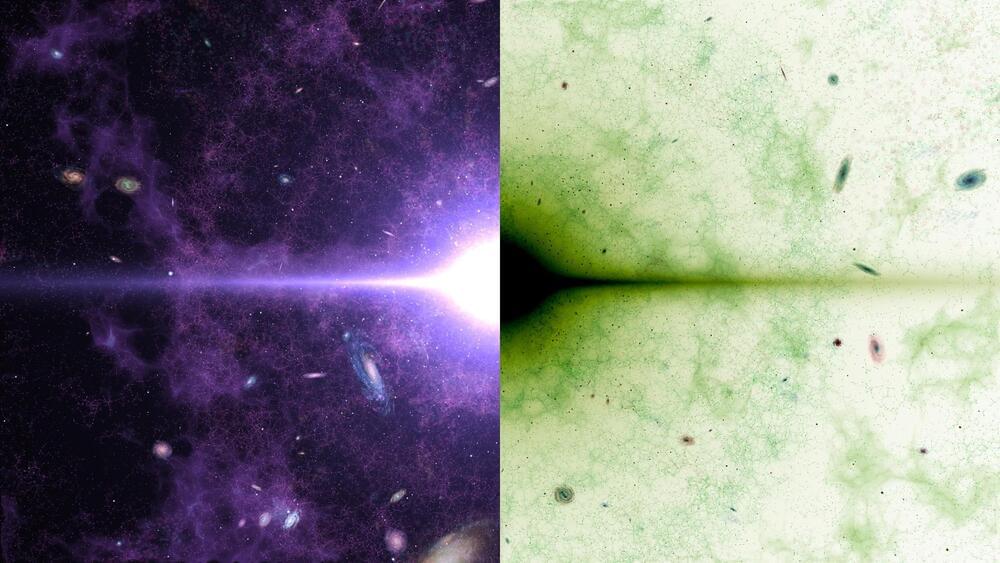

Astrophysicists at the University of California, Berkeley, now argue that the axion could be discovered within seconds of the detection of gamma rays from a nearby supernova explosion. Axions, if they exist, would be produced in copious quantities during the first 10 seconds after the core collapse of a massive star into a neutron star, and those axions would escape and be transformed into high-energy gamma rays in the star’s intense magnetic field.

Such a detection is possible today only if the lone gamma-ray telescope in orbit, the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, is pointing in the direction of the supernova at the time it explodes. Given the telescope’s field of view, that is about one chance in 10.